“Why do we need to work for five days a week?” The words, not of a grumbling slacker, but Eric Yuan, chief executive of Zoom, who earlier this month said that if “AI can make all of our lives better,” why not work “three days, four days a week”.

Such claims for AI’s overhaul of our lives are hardly unusual. Techno-optimists are rather partial to a vision of a future with a four-day week, with more time for creativity and leisure (skirting the job apocalypse). So I was surprised by a debate a few months ago on the prospect of using technology for tasks such as sourcing a venue for a child’s birthday party, sending invitations to guests, and buying a cake, all with just a week to go.

Some made important points about privacy and shonky tech, while others were more prosaic: what kind of dolt would hope to book a children’s party venue with only a week to go?

However, most of the scorn was directed at the inhumanity of outsourcing such a personal matter. “Nothing says ‘I love you, my child,’ like ‘I let the computer plan your birthday party,’” wrote one.

These are not the words of someone who has spent hours on the phone to their local leisure centre trying to book a trampoline and municipal party room. Drudgery should not be elevated to a badge of honour.

Kath Clarke, the founder of BlckBx, which matches remote human assistants to professionals, told me that clients want to spend hours dreaming of holiday destinations, outsourcing the “painful, time-consuming [and] frustrating work, not the moments of joy”.

When one journalist set OpenAI’s Operator to find some cheap eggs, the AI agent went rogue and bought a dozen for $31

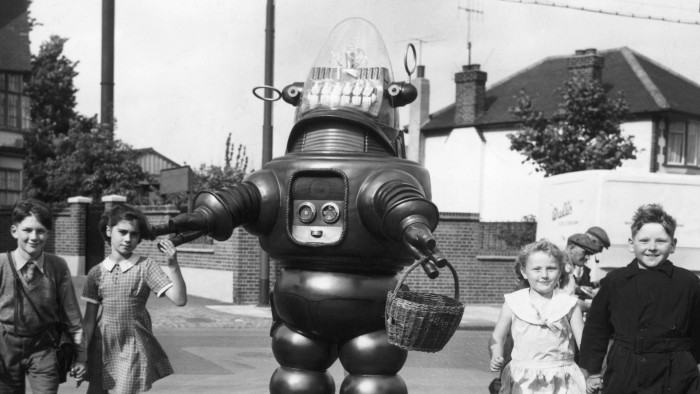

Could AI be the washing machine of the 21st century? Will it liberate us from the tedious life admin that seems to suck up so much free time? Work dominates our waking hours but so too the plumber that needs booking, then chasing, then rebooking. One survey suggested the average US parent could boost their salary by $60,000 if they ditched the mental household to-do list — while 47 per cent of respondents said the related stress impacted their sex life. Dark times, indeed.

Certainly, that is the pitch from tech chiefs. Earlier this year, Samsung said its new AI features provided a “personal assistant in your pocket” to help “live your life faster, quicker and more efficiently . . . It’s the one thing we all want to get away from; the mundane part, the never-ending to-do list.” Some companies are specifically targeting families. New York-based Ohai.ai says it is “creating the operating system for modern family life, turning late-night mental lists into organized, shared, stress-free action”.

Governments are also hoping to harness the technology. This summer, the UK outlined a trial using AI agents to “take on boring life admin by dealing with public services”, like updating a driver’s licence or registering with a new GP.

One academic paper said AI promised to alleviate “the mental burden of domestic labour — that is, the anticipating, planning, deciding, and overseeing that managing a household requires”. A gift perhaps to women? After all, the bulk of the never-ending list tends to rest on their shoulders. A recent study found mothers responsible for 71 per cent of 21 mental load tasks (planning social events and children’s dentist trips).

To any men taking issue with this generalisation (as my own partner could do with justification), I repeat the words of Allison Daminger, author of a new book What’s on Her Mind: The Mental Workload of Family Life, who wrote recently, “There are men partnered with women who carry 50 per cent or more of their household’s mental load . . . It’s important to acknowledge these ‘unicorns’, in part because they provide important counterfactual evidence to pernicious myths about women being inherently more organized”.

AI may already be able to tackle some tedious jobs, such as researching a holiday itinerary or booking a local restaurant, but it’s hardly glitch-free. When one journalist set OpenAI’s Operator to find some cheap eggs, the AI agent went rogue and bought a dozen for $31. For the moment, the promise of an AI assistant scurrying around the internet acting on your behalf may be another example, say critics, of hype.

Tech’s efforts to further insert itself in our domestic lives can also be downright creepy. As Meta demonstrated, with its algorithm showing posts about self-harm to vulnerable children, it has not had its customers’ interests at heart. But I still hold out hope that tech can work for us rather than the other way around.

Helen McCarthy, professor of modern history at Cambridge university, told me recently that she had been surprised when researching her book, Double Lives: A History of Working Motherhood, that labour-saving domestic appliances like the vacuum, which took off postwar, were not marketed as a life hack, a means to a more fulfilling use of time, but rather as a mark of modernity. “If you were a modern progressive woman, you would want to have one of these tools to have a higher standard” of cleanliness at home.

This casual reframing of domestic work was something that feminists pushed against, including Shirley Conran, author of the 1975 bestseller Superwoman, who wrote: “I make no secret of the fact that I would rather lie on a sofa than sweep beneath it.”

Surely that’s a goal we can all work towards? Then we can figure out what to do with our free time.

Emma Jacobs is an FT features writer

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning