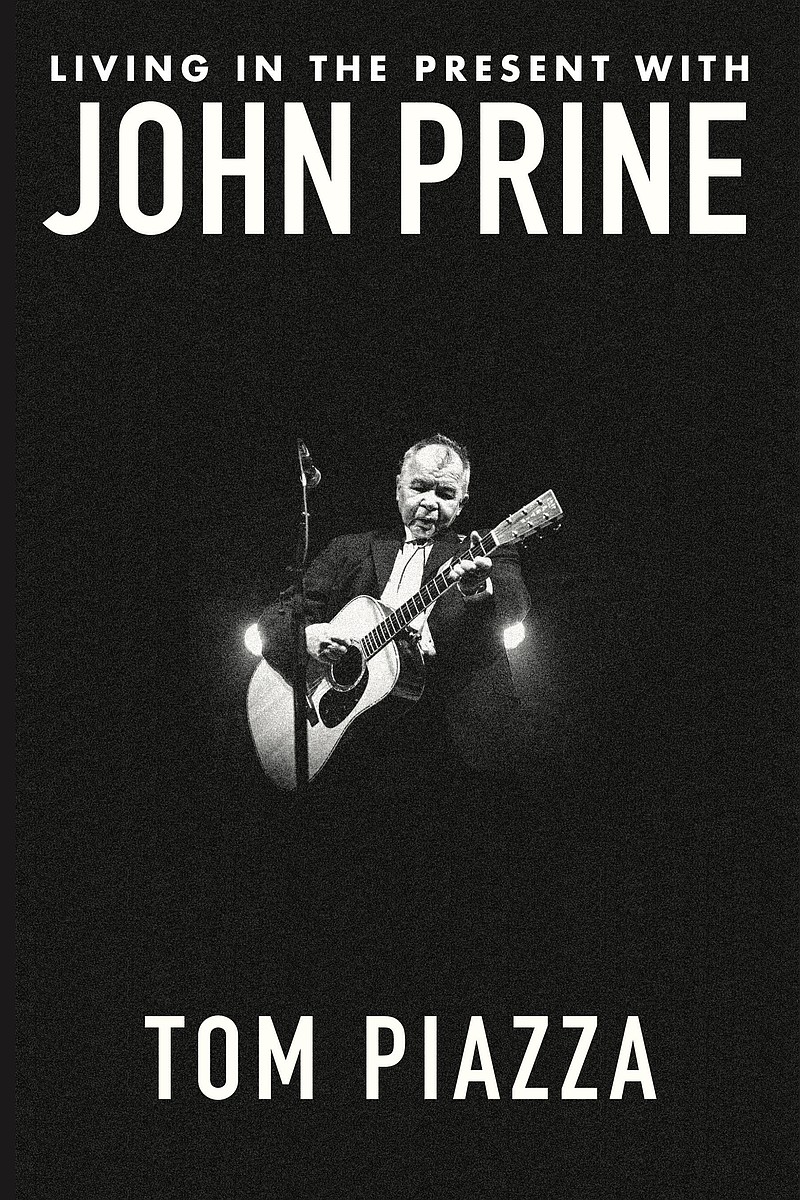

“LIVING IN THE PRESENT WITH JOHN PRINE” by Tom Piazza (W.W. Norton & Co., 208 pages, $28).

Tom Piazza’s poignant book about the late singer/songwriter John Prine is full of colorful anecdotes about the time the two spent together — a painfully short interlude of friendship that ended abruptly with Prine’s death from COVID in the spring of 2020. Recalling one of their many late-night talk and jam sessions, Piazza remembers:

The fact that John was playing my guitar and I was playing his best pal’s guitar had a mythic resonance. Handing the 0-16 back to me, he said, “That’s a magic guitar.” The whole thing was magic. Sometimes I wish I’d recorded it, but that would have undercut the point, which was to be there in the present. A recording would have been a postcard from a place where we no longer were.

Still … I wish I had that postcard.

It is easy to understand the grieving friend’s lament. And yet, an album of postcard memories might be the best way to describe “Living in the Present With John Prine.” In an author’s note, Piazza acknowledges that this deeply personal story fits no neat category, rather like its subject. It is not a biography, he says, or “a chronicle of John’s musical development, a critical assessment, an oral history or a study of his influence on American culture. Those books will come, I’m sure.”

W.W. Norton & Co. / “Living in the Present With John Prine”

W.W. Norton & Co. / “Living in the Present With John Prine”

Those books probably will come, but it is hard to imagine another work that Prine fans (and his many admiring peers) will appreciate more than this one. What started as a joint project to produce Prine’s memoir — a project just barely underway when Prine died — became “a book about friendship, and loss … a portrait, the best I can deliver, of John, and of our friendship, as he made the most of the final two years of his life.”

And so, we get to jump in the backseat of the vintage Cadillac convertible and listen in as the two first get to know each other, cruising along the ocean on Florida’s west coast. In a juxtaposition fans will appreciate, the two are discussing Prine’s views on death and immortality (explored often in his songs) when it appears the Cadillac is being pursued by a police car. Another night at home in Nashville, we can pull up a chair and join them in John’s dining room for an impromptu set of blues and roots classics that lasts until 3 in the morning.

The pair’s friendship began with Piazza’s 2018 assignment to write a profile of Prine for Oxford American. Their immediate bond grew more out of shared love of blues, fine guitars and great melodies than anything related to putting Prine’s story down on paper. Prine had never wanted to write a memoir, and Piazza was surprised when, in January 2020, Prine proposed working together to create one.

After the project was agreed on, Piazza and Prine had only two days together to record his personal story before the pandemic shut down travel and Prine fell ill with the virus. Piazza includes transcripts from those discussions, presented with comfortably simple transition mechanisms from the earlier stories. He describes the setting, his question and transitions immediately to Prine’s transcribed recollections. However brief, the sections in Prine’s voice offer compelling insights that may be new to his followers. Recalling his early exposure to music, Prine credits his older brother Dave, who introduced him to Carter Family music and took him along to venues where the folk scene was exploding. As he absorbed the Carters, Dylan, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and others, the threads began to intertwine for the teenager. Prine reflects: “When I think back, it’s no wonder I’d become a songwriter. I saw everything as being connected. Movies, dreams, imagination … It was all one thing. It was all one circus tent.”

After his friend’s death, Piazza visited Dave and Jason Wilber, the longtime lead guitarist in Prine’s band. Their stories, also in transcript form, are as quirky and comical as Prine’s circus tent analogy would foretell.

Grief forced Piazza to set Prine’s music aside for a time. In his closing chapter, titled “Not the End,” Piazza recounts his emotions when he was able to play it again: “I … experienced a renewed awe, not just for the incredible quality and depth of the songs, but for the man who made them — his insight, compassion and deep feeling both for human resilience and for human frailty.”

It is a risky enterprise to predict the thoughts of a beloved character who has passed on, but I believe Prine would have been proud of this book. Appreciative of each treasured moment, it is profound in its simplicity, mirroring Prine’s work in its depiction of the man’s own resilience and frailty and his delight in living. What a joy to go along for the ride. The last page came all too soon.

For more local book coverage, visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.