After a long period of underperformance, emerging markets are shooting out the lights. The iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF EEM is up 28.7% this year. Its tiny sibling iShares MSCI BIC ETF BKF, which focuses on the powerful BRICS economies, is up 23.4%. That compares with a 16.6% return for the Morningstar Global Markets Index.

That performance may reflect the realignment of the global order, in which major emerging markets may play a role equal to the G7.

The acronym BRIC was coined in 2001 by Goldman Sachs economist and former UK Treasury minister Jim O’Neill. He argued that by 2050, Brazil, Russia, India, and China would dominate the global economy. In 2010, South Africa was added to the list and the acronym became BRICS. More nations have been added since, and the cohort is sometimes referred to as BRICS+.

This realignment has major implications for risk and reward, altering how investors large and small allocate their wealth, according to Maria Vassalou, head of Pictet Research Institute. Vassalou is a longtime analyst of risk, having worked at a Who’s Who of hedge funds. She says there are also plenty of opportunities.

Leslie Norton: When you say BRICS, one usually thinks of commodities.

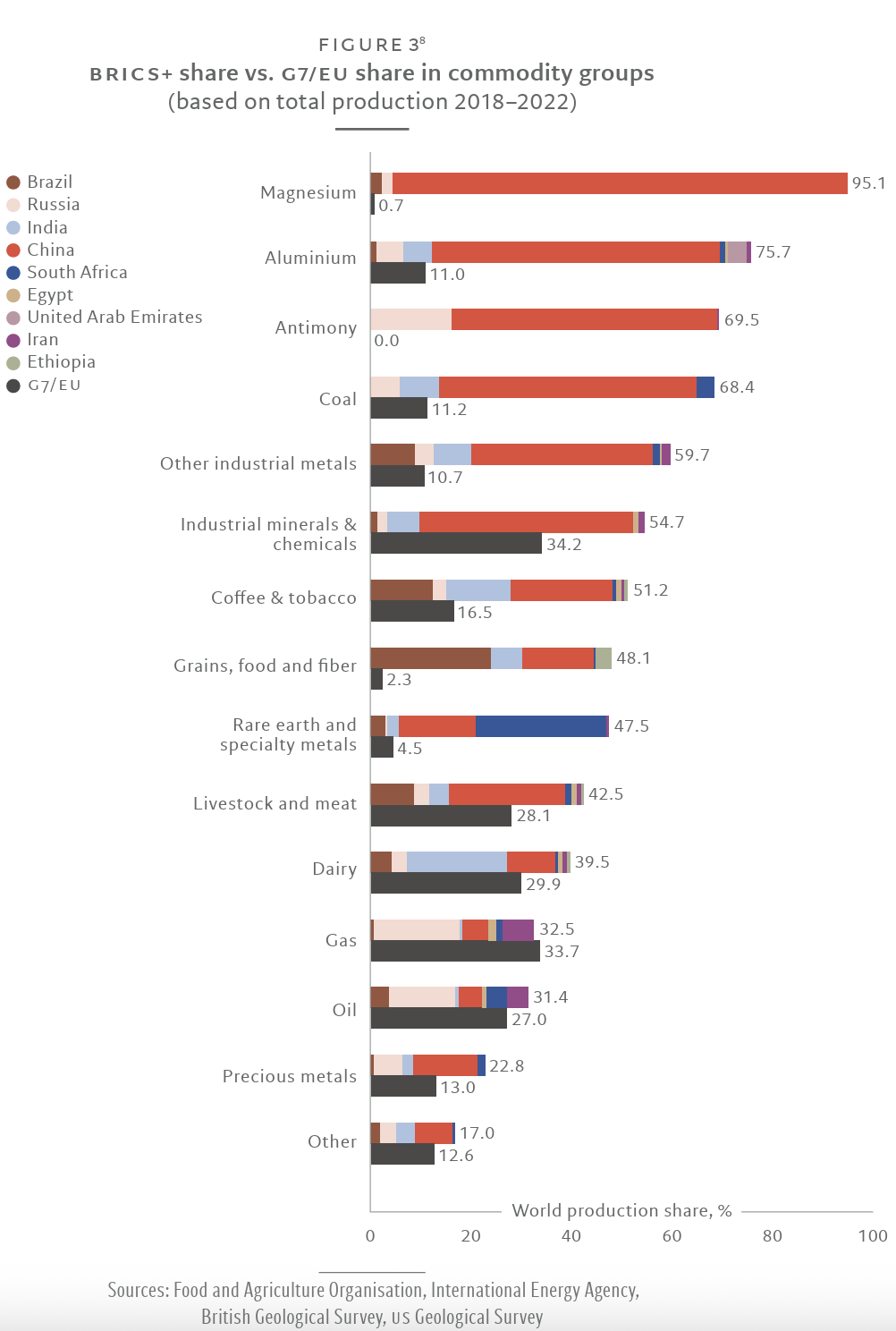

Maria Vassalou: It’s not just commodities. China is challenging the United States and global technological leadership. Russia and India are developing military applications. On the energy front, you have Russia, Brazil, the United Arab Emirates. Iran is an additional member. The BRICS have a range of commodities, from minerals and rare earth to industrial metals, food, energy, and precious metals.

BRICS has emerged as a very powerful coalition that challenges the West. They exhibit strengths in factors such as technology, energy resources, commodities, maritime trade routes, military capabilities, and demographic advantages, which will all be important for economic growth and geoeconomic dominance going forward. They’re trying to strengthen their coalition along these lines. Individual countries are admitted because they provide some advantages along one or more of those dimensions. Interestingly, these are the dimensions in which most G7 countries lack advantages.

Source: Pictet Research Institute.

Source: Pictet Research Institute.

Norton: How has the G7 reacted?

Vassalou: We’ve seen a powerful reaction from the US to counter the rapid rise of China. There’s a clear redirection of foreign policy toward Asia rather than Russia. That has realigned the G7. As Russia is no longer the US’ competitor, Europe’s geopolitical significance has been degraded. The Draghi report for Europe focuses on efforts to reindustrialize and having an industrial strategy.

During globalization, Western economies grew increasingly specialized and reduced their emphasis on manufacturing. The US shifted primarily toward services while continuing to lead in technology and innovation. But the lack of domestic manufacturing capabilities for the products that use those technologies prevent the US from benefiting from the virtuous circle of synergies and learning that exists between the design and development of a technology and its production, undermining its own future technological capabilities. It’s a huge wakeup call.

Norton: Tell us about the BRICS pecking order.

Vassalou: China is the leading partner, and Russia the junior partner. Apart from the original members, a large number were admitted afterward, such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the UAE. You have countries like Saudi Arabia, which is not a full member but is affiliated, and then a list of prospective members. Most countries are in the coalition for economic diversification, and a number are trying to maintain a good relationships with the West. Some are outright anti-American, such as Iran and Russia, and among the prospective members, Belarus, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Turkmenistan.

Norton: What’s in it for China?

Vassalou: China faces increased barriers to the US and European markets. It needs alternative markets. It has a short-term problem of overproduction and it needs to export goods to maintain its growth rates. Otherwise, it risks domestic unrest. Once past this period, it has a very good long-term trajectory due to automation, innovation, technology.

Over the medium-to-long term, the US has the opposite problem. It has a much better economy right now, despite some signs of a slowdown. It’s the leader in the global financial system, a provider of safe assets, of the reference currency, and of technology and innovation. The US is trying to redirect its economy toward a bigger emphasis on industrial production and technology and to buy time by slowing down China, constraining exports of important chips and so forth. The BRICS+ markets provide an alternative for China. They cannot replace the US and European markets, but they mitigate the problem.

Norton: How about for other economies?

Vassalou: Emerging markets and frontier markets have a long list of grievances going back to colonial times. More recently, it’s about their feeling that their voices in the global discussion aren’t proportional to their importance. This particularly applies to India and Brazil, which have always felt they should be part of the UN Security Council. BRICS gives them a voice. China is smartly managing this, making them feel much more equal. Also, China doesn’t lecture them on human rights or how they should run their countries. It’s an economic rather than ideological, moral, or ethical union.

Norton: What does this mean for inflation?

Vassalou: We’re exiting a period of globalization, free capital flows, free trade that was obviously deflationary. To the extent that you constrain trade or try to replicate production in different markets, that will have a short-term inflationary effect.

Norton: Some have called for a BRICS common currency for trade and investment within the bloc.

Vassalou: The prospect of a common currency is remote, at least for 10-plus years. None of these countries has the economic stability and institutional framework to produce safe assets to be used as collateral in international transactions, and this is the basis for creating a reference currency. They have to issue more debt, open their capital markets, strengthen their institutional base.

You also need credibility that this guarantee will be stable and reliable. Right now, whether anyone likes it or not, the major provider of safe assets remains the US. In fact, because global growth is accelerating more in developing countries than in developed countries, the availability of safe assets is declining, which puts strain on the global financial system.

Norton: Can China play this role?

Vassalou: Maybe down the road. For now, it doesn’t have open capital markets, and needs to solve its property and debt issues. One reason they have capital controls is that the moment they opened the market, a lot of capital would flee. Also, being a reference guarantee provider comes with certain responsibilities that would work against China’s business and economic model.

A basket of currencies wouldn’t really resolve the issue. People use stablecoins to transact, but effectively still need to hold US Treasuries as reserves against them. They’re avoiding the US dollar payment system, which may help them avoid sanctions, but they’re not de-dollarizing.

Norton: Where does Russia fit in?

Vassalou: One reason the predictions about Russia’s demise after the Ukraine invasion didn’t materialize is that Russia was able to continue to export energy to China and the BRICS and get paid through all these alternative systems. It’s ironic; by promoting the use of stablecoins, the US government effectively undermines its own sanctions.

Norton: How will this affect how we think of asset classes?

Vassalou: Traditionally, assets were divided into developed and emerging. Developed economies had a diversified industrial base, exported a lot, were very open to international trade, had stable laws and regulations, and had technology leadership. Emerging markets were the opposite.

This distinction between emerging and developed markets is becoming less relevant. The main drivers of growth are still technology, energy resources, commodities and productivity advancements. The BRICS coalition has advantages that can propel its countries to the forefront of economic development: technology, energy resources, the entire spectrum of commodities, access to key maritime trade routes, significant military capabilities, favorable demographics, and consumption growth. Many G7 countries lack such advantages. Europe is ill-prepared for the drivers of growth going forward.

Norton: Will investors equal weight or overweight what’s currently considered emerging markets?

Vassalou: There are two things to consider. One is the importance of economies, the other is how you access the opportunities. US capital markets represent a much bigger percentage of the global economic activity than the US share of global GDP. In capital markets, what is important is how to access investment opportunities. You may be accessing investment opportunities in BRICs through companies listed in a Western country. The focus should be on where they derive their revenues.

The other distinction is between private and public markets. The competition for economic and geopolitical dominance across different countries and regions may reduce the incentive for some firms to go public. The availability of capital may also become much more regional. So private credit may become more important.

Norton: What investment products will become popular in the new world?

Vassalou: Thematic investing will be much more important. There’s also this mixture of private and public assets, so multi-asset portfolios. Managing those exposures actively is important because demographic changes will greatly affect demand and consumption preferences and therefore growth. Technological revolutions related to AI will play out mostly in the 2030s. That will have a great impact on productivity growth at the same time that you have a significant geopolitical realignment. We don’t know where it will end up. We may have more conflicts, more changes in the power structure.

Norton: What about passive index funds?

Vassalou: At this point, being passive is almost more risky than being active, because we are at an inflection point from one global financial arrangement to another that isn’t yet well-defined. The construction and exposures of the portfolio need to be regularly reexamined, with risk actively monitored and recalibrated frequently, and with downside protected.

Norton: What happens in a global market shock? We do have them every so often.

Vassalou: US debt levels are significant, but the debt overhang has become a global phenomenon. The risk of another market crisis is increasing because of all these uncertainties. You need to be diversified much more than in the past and take less risk. A lot of risk models, based on historical data, are likely to underestimate the amount of risk. In the alternatives business, where people use a lot of leverage, gross exposure of portfolios would probably need to go down.

Norton: Does the US dollar retain its safe-haven status?

Vassalou: For the foreseeable future. At the moment, there are no credible alternative safe assets to US Treasuries. There are efforts to reduce the reliance of global transactions on the US dollar. One is stablecoins. But that isn’t a de-dollarization effort, as most major stablecoins are pegged to the US dollar. They do, however, bypass the US dollar settlement system.

Norton: Global transactions in renminbi are jumping.

Vassalou: That pace is unlikely to continue, unless China abolishes capital controls and embarks on the reforms needed to create credible safe assets. If BRICS and other countries continue to expand their use of renminbi in the absence of such reforms by China, they will increase the systemic risk with the potential of creating another Asian financial crisis. So far, their actions show that their main goal in the foreseeable future is to bypass the US dollar transaction settlement, not to de-dollarize, hence their increased use of stablecoins.