A recent Mongabay investigation found widespread government purchases of shark meat in Brazil to serve in thousands of public institutions.The series has generated public debate, with a lawmaker calling for a parliamentary hearing to discuss the findings.Here, Mongabay’s Philip Jacobson and the Pulitzer Center’s Kuang Keng Kuek Ser explain how we built a database of shark meat procurements.

See All Key Ideas

Mongabay recently published an investigation revealing widespread Brazilian government purchases of shark meat to feed schoolchildren, hospital patients, prisoners and more. The series has generated public debate in the South American country, which, perhaps surprisingly, is the world’s largest consumer and importer of shark meat. The procurements raise concerns because sharks are being overfished — globally, their populations in the open ocean have declined by an estimated 71% over the past half-century — and their meat tends to contain high levels of heavy metals, which can be especially dangerous for young children, pregnant and nursing mothers, and other vulnerable groups.

As part of the research, we spent months combing through dozens of websites where Brazilian government agencies are legally required to publish their procurement records. It was challenging work, hunting down droplets of relevant data cataloged with inconsistent search terms across multiple obscure portals. In this article, we’ll tell you how we went about it in hopes of inspiring and easing the way for other journalists and researchers to continue this line of inquiry.

Because it was also richly rewarding: We uncovered 1,012 shark meat tenders issued since 2004, and identified 5,900 public institutions — preschools, homeless shelters, maternity wards, military bases, elderly care facilities, governor’s residences, and more — that potentially received shark meat as part of these procurements. (Brazil-based Mongabay reporters Karla Mendes and Fernanda Wenzel also played key roles in the investigation, following up leads on the ground turned up by our data work.)

The impetus for the investigation was straightforward. We knew some government agencies were buying shark meat for schoolchildren. In 2021, for example, São Paulo’s municipal education department cancelled a planned purchase of 650 metric tons of shark meat after marine conservation group Sea Shepherd Brazil criticized it, earning TV coverage; that same year, the nearby city of Santos announced it would ban shark meat from school meals, a decision it said spared nearly half a metric ton of shark from being fed to kids.

Experts told us shark meat procurements were happening elsewhere too. But aside from the aforementioned cases, plus a few passing mentions in a handful of academic papers from the 2010s, we could find no report or study on the full extent of the phenomenon. Questions remained: Just how widespread were Brazilian public purchases of shark meat? Which agencies were buying it, and who were they feeding it to? What species were they buying? Did the officials in charge of these procurements even realize cação — the generic name under which shark meat is packaged and sold in Brazil — was shark?

As we asked around, we learned about the online portals where government agencies publish procurement records. It seemed like a good place to start.

Shark meat on sale at a fish market in Santos is labeled as “cação,” a generic term whose true meaning is unknown to most Brazilians, surveys show. Image by Philip Jacobson/Mongabay.

Shark meat on sale at a fish market in Santos is labeled as “cação,” a generic term whose true meaning is unknown to most Brazilians, surveys show. Image by Philip Jacobson/Mongabay.

How we searched the portals

Brazil has 26 states and about 5,570 municipalities. Each jurisdiction is supposed to have its own publicly accessible online database of procurement records, including tender announcements, bidding records and award notices.

Searching every one of those portals was far beyond our capacity, so we picked a few key jurisdictions to focus on. Our goal was not to identify every shark meat procurement that’s ever happened, but rather to test the hypothesis that such procurements are widespread.

After locating the portal for the state or municipality we wanted to search, typically via the jurisdiction’s homepage, we had to figure out how to navigate the portal and whether we could use it to find shark meat tenders. This wasn’t always straightforward: Portals varied greatly in design, and some were quite archaic, with limited search functionality. When possible, we wrote custom scrapers in the Python programming language to automate parts of the process, but identifying shark meat tenders was rarely as simple as typing “cação” in a search box. Reasons for this include:

The portals typically provide a limited number of fields with which users can search for tenders (contracting agency, tender ID, year of issue, etc.). The list of items intended for purchase is rarely a searchable field. We therefore focused our keyword searches on the objeto (“object” in English) field, which summarizes the tender’s overall purpose (“buying fish for school meals in City X,” for example) and was usually searchable.

Very few shark meat tenders, we found, actually mention shark meat in the objeto. We therefore searched keywords like “peixe” (fish), “carne” (meat) or “alimentação” (nutrition/feeding), and then examined the results to find tenders with shark meat. To do this, we had to go down the list of results and open up each tender page, one by one. Often we had to click through layers of additional pages and/or download attached files to find the items list, where we could see if shark meat had been included.

Besides being a Brazilian word for shark meat, -cação is a common suffix in Portuguese. So even though some tenders did mention cação in the objeto, searching for that word in that field usually returned an overwhelming number of false positives. The portals tended to lack quoted search functionality to isolate specific terms that would have helped us filter out these false positives.

The downloadable files where the items lists were often found were usually PDFs, but they could also be DOC files, spreadsheets or other file types, and they tended to organize information in their own idiosyncratic ways over dozens, even hundreds, of pages. This lack of consistency impeded our ability to automate the information extraction process, meaning we usually had to read through the files ourselves in order to extract the desired information — not just whether cação was on the items list, but also data like purchase price, winning bidder, and more. It was a tedious and time-consuming exercise.

Generally speaking, our strategy was to first confirm that a particular search in a given portal would yield results that included at least some shark meat tenders. Then, if there were a very large amount of results, we would use Python scripts to automate checking those results for mentions of shark meat.

The first four states

To start, we chose four states: São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais — the three most populous states in Brazil — and Paraná, the sixth-most populous and one we’d heard was buying shark meat.

We also wanted to look at the southernmost states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, where shark fishing and cação consumption are known to be widespread, but their portals were difficult to navigate, so we moved on. (Later, we identified shark meat procurements by state agencies in Rio Grande do Sul via another Brazilian website, www.portaldecompraspublicas.com.br, which compiles tenders from various jurisdictions. We also identified municipal shark meat purchases in both states via several municipal portals.)

Paraná

Portal search page (licitações): https://www.transparencia.pr.gov.br/pte/assunto/5/115?origem=3

Initially, we were confused about how to navigate this portal because there were two ways to search for tenders. We contacted Paraná state officials and were advised to search for both licitações (auctions) and contratos (contracts) in the database for tenders. After several rounds of searching and comparing data, we realized that both gave us the same tenders, but the search results from licitações had more detailed information.

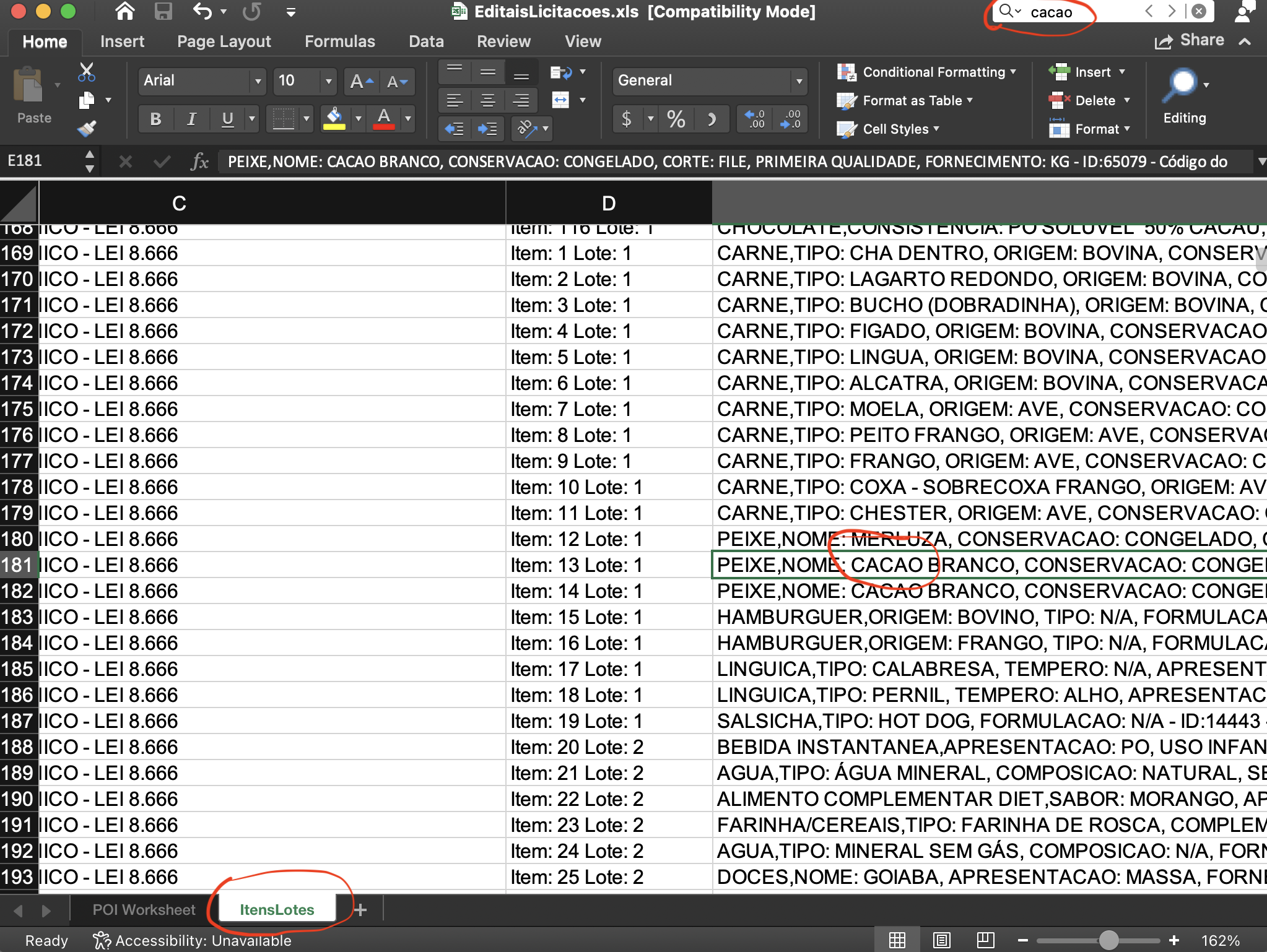

This was one of the rare portals where the list of items to be procured was a searchable field (called item/palavra-chave). We wrote a scraper that searched for the terms “peixe” and “pescado” (another word for fish), in both the item and the objeto fields, and then downloaded each result — there were more than 900 — as a separate XLS file. The scraping was challenging as the website loaded very slowly or failed to load, and the back (voltar) button sometimes failed to work properly.

After that, we searched each file for “ cação”, with a space in front, and its variations — “ cacao”, “ cacão”, “ caçao”, “ cação” — then manually checked the ones where one of those words appeared in order to confirm it was actually a shark meat tender and not a false positive. For the approximately 50 verified shark meat tenders, we then manually recorded information like supplier company, purchase price, etc., into our own spreadsheet.

São Paulo

Portal search page: https://www.imprensaoficial.com.br/ENegocios/BuscaENegocios_14_1.aspx

Unlike the Paraná portal, the item and even the objeto fields were not searchable here. Despite this obstacle, we were driven to devise a workaround because São Paulo state was said to be the biggest consumer of shark meat in Brazil. We ended up using a scraper to download every tender issued between 2004 and 2024 filed in the portal under Subárea: Alimentação, a category we confirmed held at least some shark meat tenders by experimenting with some manual searches and clicking through the results. This gave us about 75,000 tenders to start with.

In this portal, each tender had its own page, usually with additional data and documents; the edital, which is the formal invitation to bid published by the contracting agency, was downloadable, and other documents, like the approval notice, were copy-pasted into separate webpages. We wrote another scraper to access more than 350,000 document webpages across the 75,000 tenders and search the contents of each page for the keywords “pescado”, “peixe”, “ cacao” (with a space in front) and its variations. We found that around 1,000 tenders contained these keywords. We then checked each tender ourselves to verify if it actually included shark meat (false positives could arise, for example, from words like indicação being split by a line break) and, if so, recorded the purchase details in our own spreadsheet. We ended up with 701 confirmed shark meat tenders from this portal.

Minas Gerais

Portal search page: https://www1.compras.mg.gov.br/processocompra/pregao/consulta/consultaPregoes.html

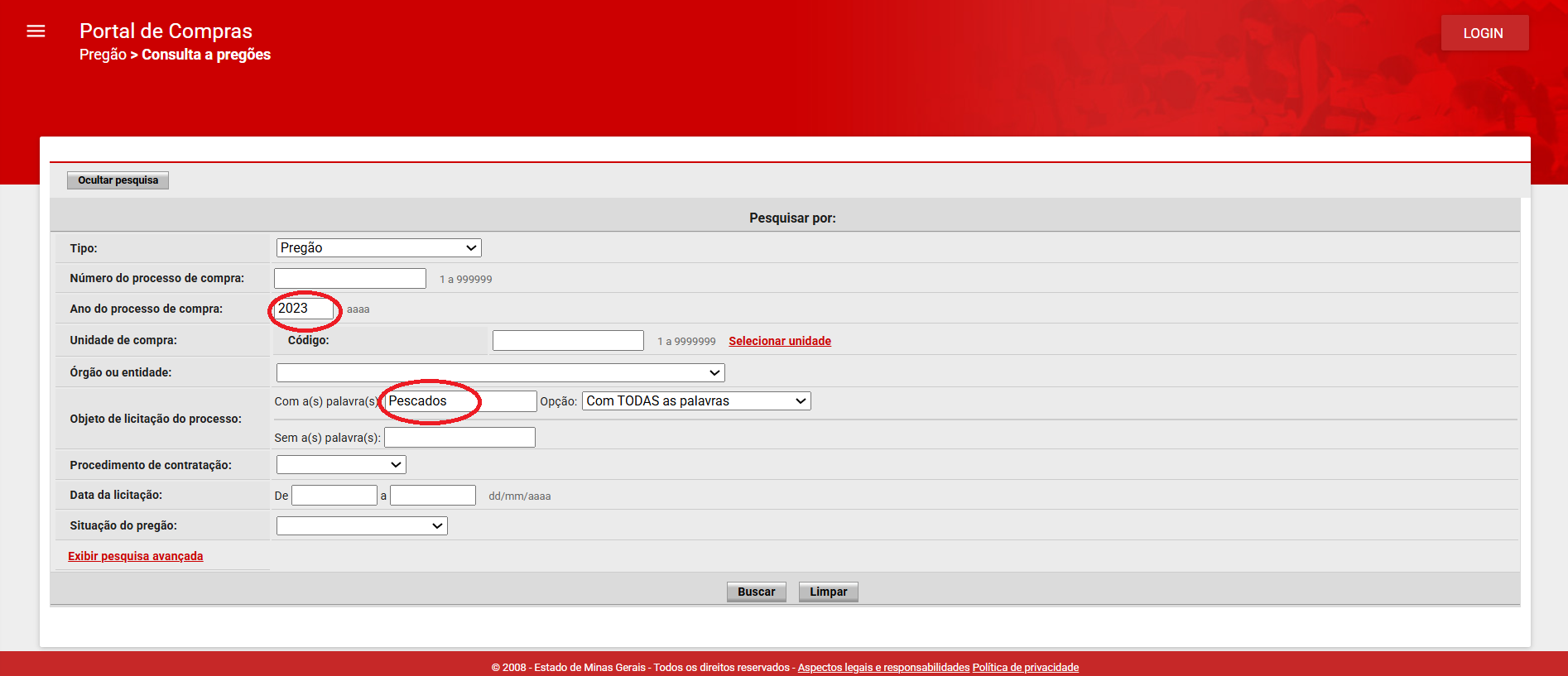

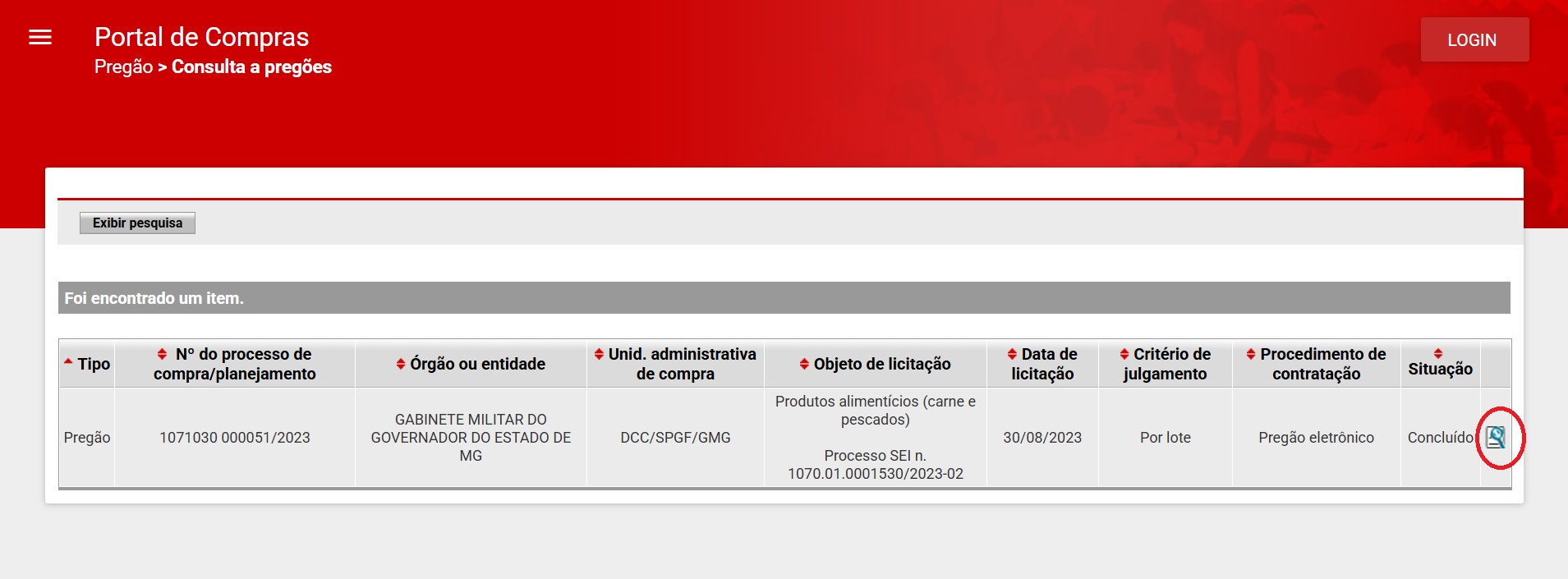

This portal was relatively easier to tackle, but we needed a VPN to access it from certain locations outside Brazil. Our search in the objeto field using six keywords (alimentação, alimenticios, refeições, refeição, peixes, pescados) returned close to 900 tenders published since 2009, the earliest available year in this portal. We scraped the details of each tender and downloaded close to 3,000 edital files in various formats.

Search the objeto field using keywords and repeat it for each year, as there’s a limit on how many results can be shown in each search.

Search the objeto field using keywords and repeat it for each year, as there’s a limit on how many results can be shown in each search.

For each tender in the list of search results, click the magnifying glass icon to open the tender page.

For each tender in the list of search results, click the magnifying glass icon to open the tender page.

Scrape the tender data and download the attachments under the field “Edital do pregão” and search those for cação.

Scrape the tender data and download the attachments under the field “Edital do pregão” and search those for cação.

We converted all DOC and DOCX files to PDF. Then we wrote another Python script to search through the attachments and identify those with the words “ cacao” and “ cação”. For files that couldn’t be converted to PDF, we did the same but manually. We reviewed these documents ourselves to verify if they mentioned shark meat and were able to confirm 22 tenders.

Rio de Janeiro

Portal main page: https://compras.rj.gov.br/

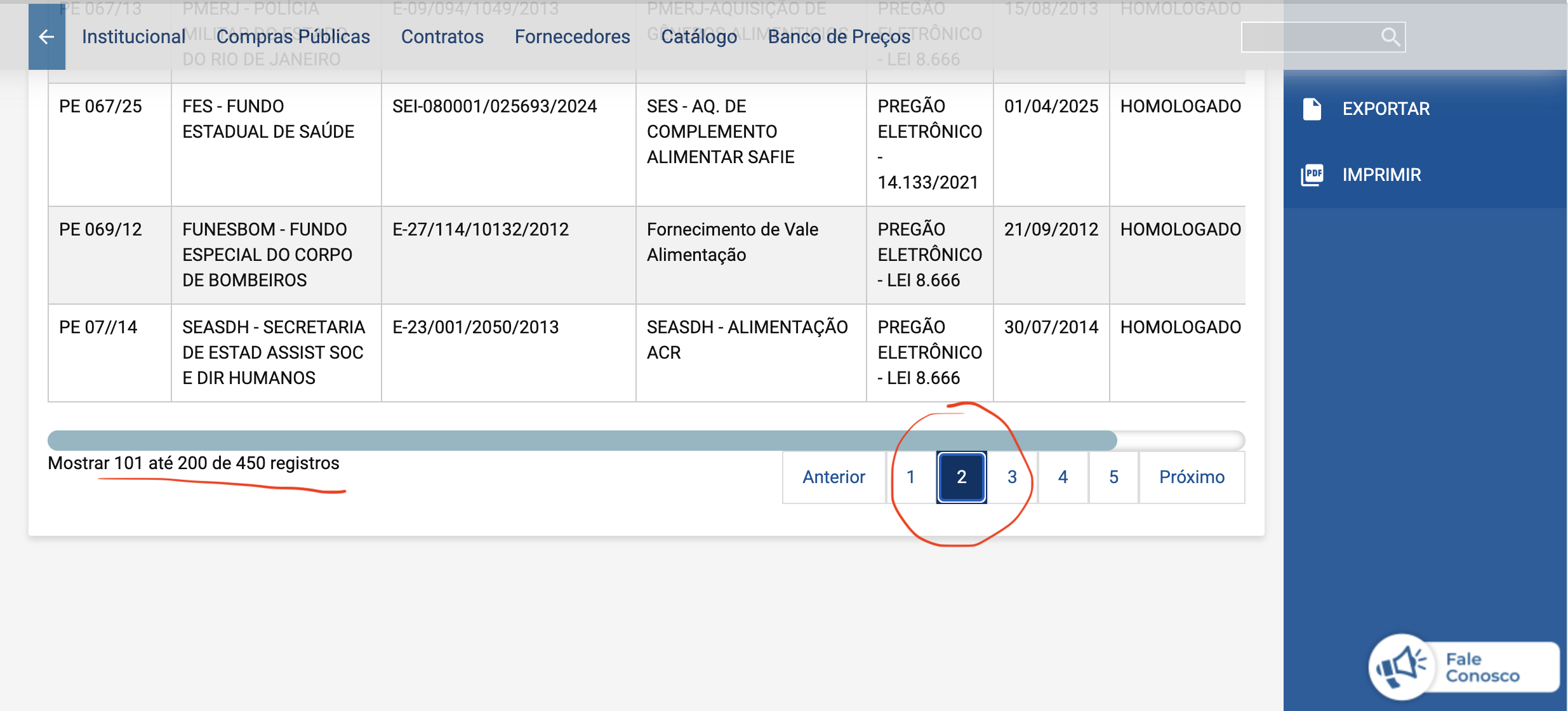

Search panel for concluded tenders: https://compras.rj.gov.br/EditaisLicitacoes/listar.action?origemIndex=true

Search panel ongoing tenders: https://compras.rj.gov.br/EditaisLicitacoes/listar.action?origemIndex=true

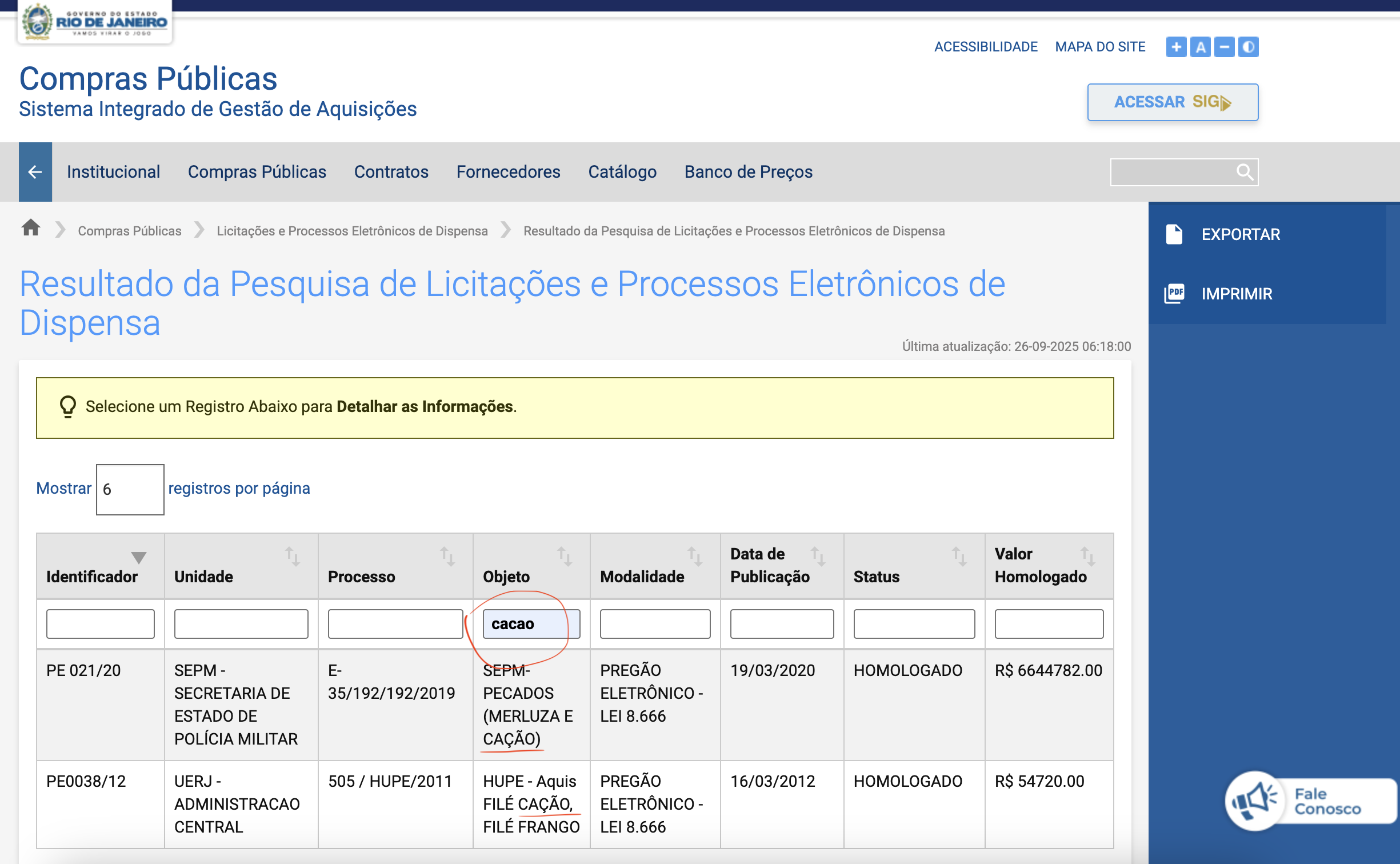

Here again we focused on the objeto field. Searching for “ cação” (with a space in front) yielded two results, both actual shark meat tenders. Peixe and pescado also turned up some results (20 and four, respectively), some of which turned out to be shark meat tenders.

Searching for “cacao” in the objeto field yielded two results, both shark meat tenders, though a small number.

Searching for “cacao” in the objeto field yielded two results, both shark meat tenders, though a small number.

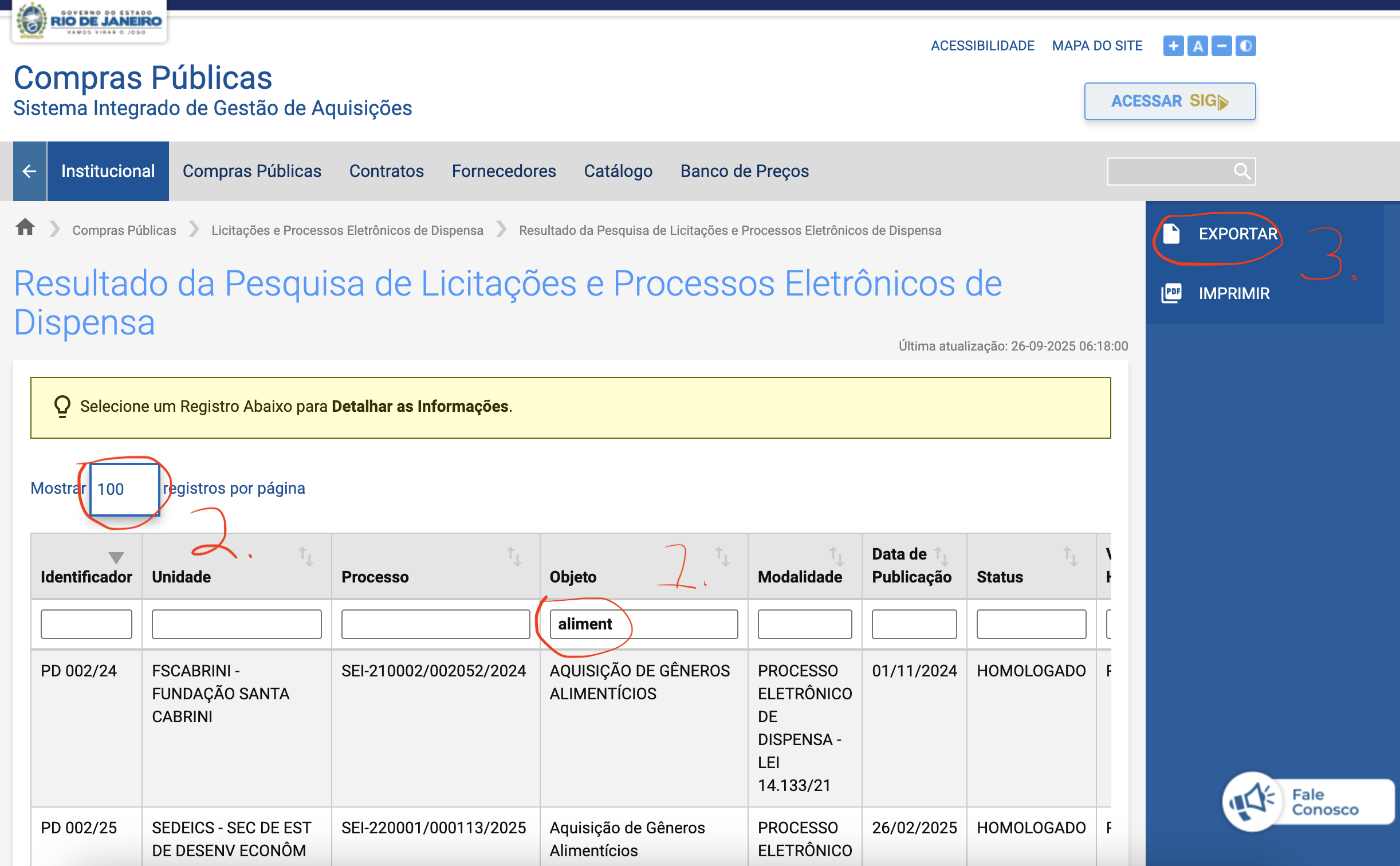

Given the small number of results, we experimented with additional search terms and realized we could use the keyword “aliment”, as it returned tenders with words like alimentos (foodstuffs), alimentação (nutrition) and alimentícios (food-related) in the objeto, to find additional shark meat tenders. At this point, it was too late to go back and redo the São Paulo portal with this search term, but we applied it going forward and it proved the most fruitful overall. (Congelado, meaning frozen, and refeiç for refeições/refeição, meaning meals/meal, along with carne, also helped us find shark meat tenders in some portals.)

Searching for “aliment” turned up 467 results. This portal allowed the user to export search results as a spreadsheet where the items for each tender were visible and searchable, enabling us to easily determine which ones had shark meat. Given the relatively small number of results, it would have taken longer to devise a scraping method than to search it ourselves, so we did it manually. Our process was as follows:

Search for “aliment” in the objeto field.

Set the portal to show 100 results per page (the maximum amount).

Export the data into a spreadsheet.

Go to the second results page (101-200) and export that data into another spreadsheet. Repeat for each results page.

For each exported spreadsheet, go to the sheet titled Items/Lote, and do a text search for “ cacao” (with a space in front of it) to identify any shark meat tenders.

In this way, we identified tenders with cação on the items list. For each such tender, we found its page on the portal, confirmed whether the tender had proceeded to the award stage (some were cancelled before the award stage and therefore omitted from our data), and if so, logged the other data points we wanted, such as supplier name, final price, final amount, etc. This often entailed downloading and reviewing documents like the edital.

Our experience with this portal drove home the point that automating the process with scrapers and coding scripts only made sense if there were enough results, as with São Paulo state, that doing so would actually save us significant time. For most portals, it seemed more efficient for our purposes to search them manually, so that’s what we ended up doing from this point on.

Other data sources

Besides those four states, we manually reviewed dozens of additional municipal and state transparency portals. For a list of the portals where we found shark meat tenders, see the “List of data sources” in this spreadsheet.

Our means of choosing additional portals to look at wasn’t particularly systematic. We tried to examine most of the biggest cities and states in Brazil, giving their portals at least a cursory look to see if we could quickly identify shark meat tenders.

Google, with its advanced search functionality, proved useful in identifying shark meat tenders, often in small towns where we wouldn’t have looked otherwise. Google searches like this, this and this threw up links to procurements in many jurisdictions, and when we found a shark meat tender that way, we could go directly to the jurisdiction’s portal to see if we could find more.

Compiling the recipients

Besides establishing that public procurements of shark meat were widespread, we also wanted to determine precisely where the meat was being served.

Some tenders made this clear in the objeto field. For example, each tender from the São Paulo state prison system was usually to buy food for a single penitentiary, so if shark meat appeared on the items list, we knew right away which facility was getting it. Most tenders, though, procured foodstuffs for multiple sites at once, and in some cases for different kinds of institutions overseen by different government agencies. In those cases, we didn’t just want to confirm that the tender included shark meat — we also aimed to identify the particular schools, hospitals or other institutions that the shark meat was being purchased for.

In many cases, this was easier said than done. Complicating factors included:

The list of recipient units wasn’t uploaded for every tender.

When it was available, the recipient list could usually be found somewhere in the edital or terms of reference, which itself consisted of multiple annexes. But these documents could be hundreds of pages long, and the recipient list might appear in any number of places within them, and with inconsistent formatting.

Even if the recipient units were named, it wasn’t always clear which facilities were getting which foodstuffs. In some cases, the tender did specify which products were for which facilities — the Paraná state portal, for example, was very clear about this. We wrote to the contracting agencies behind a few dozen of the biggest tenders to ask which units got shark meat in the tenders we found (among other questions), but most didn’t respond. If we couldn’t say for sure which units got the shark meat in a given tender, we included every unit it named on our master recipients list. For that reason, that list should be considered a list of sites that potentially, rather than definitively, received shark meat.

Once we had the recipient lists from the various tenders, we had to extract the unit names for inclusion on our own master list. Since the lists were usually in PDF or, less often, DOC format, we had to use conversion tools to convert the lists into machine-readable format as CSV (comma-separated values) files. We used a combination of tools to carry this out: Google Drive (by opening PDF files with Google Docs), Tabula (open source) and ExtractTable (paid).

The lists were often messy. For example, some included just the unit names, while others had details like addresses and contact information. These details might be written in a table or a single line of text. In some cases, we had to split the name, street address, neighborhood and other details before the unit could be recorded in our master list, which we published as a searchable table at the bottom of our first article.

We also had to remove duplicates from our master list, as our goal was to count the number of unique recipients, and many recipients appeared in multiple tenders. In some cases, the same recipient showed up in different tenders with its name written slightly differently, or with a typo in its name that made it look like a different recipient. There were also distinct entities with very similar names; two schools named after the same public figure in different cities, for example. We had to ensure we weren’t double-counting.

To address this, we used the clustering function in OpenRefine, an open-source tool designed to work with messy data, to group recipients with similar names together. Then we manually compared their addresses, neighborhoods, municipalities and states to determine if they were duplicates. It was a painstaking but necessary process to bulletproof the integrity of our data. All told, we identified 5,900 unique recipients.

Next, we manually classified those units into several categories: school, prison, health care, military, social services, police, and other, which was helpful for data visualization purposes.

For the 5,391 schools we identified, we wanted to know how many offered early childhood education, given the risks of heavy metals for young children. This turned out to be a problem that we didn’t manage to solve completely. Since government schools can be managed by municipal, state or federal agencies, there’s no central database that says whether a particular school has early childhood education, so we needed to check the schools one by one.

First, we tried running the school names through large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT Pro, Claude and Google Gemini. We asked the LLM to search the internet for each school, visit websites that mention the school, read the websites to produce a summary of the school and determine if the school offers early childhood education. The results were unreliable; we caught the LLMs making up fake websites or mixing up one school with another.

We ultimately devised a quicker solution that could verify a large number of schools without checking them one by one. Most of the school names had an acronym indicating the type of school, and some of the acronyms indicated the offering of early childhood education. For example, CMEI (centro municipal de educação infantil) means municipal center for early childhood education; EMEIF (escola municipal de educação infantil e fundamental) means municipal school of early childhood and elementary education; and UMEI (unidade municipal de educação infantil) means municipal early childhood education unit. School names with the word creche (daycare) were also clearly for young children. Based on such acronyms as well as some supplementary Google searches, we identified 1,153 schools catering to young children among the 5,391 schools on our recipients’ list. There may be more; we didn’t have time to check them all. But the data clearly show that shark meat going to early childhood education centers is a widespread phenomenon. This helped inform the interviews with government officials that we did after gathering the data.

Limitations

Our final list of 1,012 Brazilian shark meat tenders should be taken as a floor, with the true number issued likely to be significantly higher. Reasons include:

We lacked the capacity to review the portal from every state and municipality in Brazil (far from it).

Even in the portals we did search, there could be many more shark meat tenders that we didn’t find.

Not all portals have published tenders from 2004. For example, the Minas Gerais portal only had tenders since 2009.

We found some tenders seeking to procure “fish” without specifying the type, raising the possibility that shark meat was purchased via these tenders as well.

Some tenders had items requesting “shark meat OR tilapia,” “shark meat OR hake fish,” etc. Tenders for around 20 hospitals under the Minas Gerais state health agency were like this, for example. We omitted such tenders from our final data set, but they may have ended up procuring shark meat.

The tenders in our data set are almost all direct purchases, where an agency orders a specific amount of shark meat. But we also found many tenders using the outsourcing model, where a company is contracted to provide meals for a school system, a prison, etc., over a certain time period. In some cases, it’s possible to see in the edital or terms of reference that shark meat is part of the meal plan, and we included those tenders in our database, with no figure listed for the amount of shark meat procured. In many cases, though, tenders using the outsourcing model didn’t have clear information about what was to be served. Oftentimes they included “fish” without mentioning the kind, for example. These tenders seem to have become more common in recent years.

From another perspective, the approximately 5,400 metric tons of shark meat from the 1,012 tenders in our data set could be viewed as a ceiling, because tender quantities represent maximum supply volumes, and actual deliveries over the course of the contract period may be lower or even zero. Some portals had delivery notices available for download, but many didn’t. Even if they were available, there could be hundreds just for a single tender, so we didn’t review those as part of our investigation.

The 1,012 tenders in our data set only include tenders that advanced to the award stage, where a winning bidder was chosen to supply a particular amount of shark meat at a certain price. We found many calls for tender that included shark meat but where the tender was cancelled for some reason, or where no supplier was chosen for the shark meat item, so we didn’t include those in our data.

For the relatively small number of tenders that had incomplete information in terms of the amount ordered, the amount paid and/or the recipient units, we included them in our data set but excluded the missing information from our analysis.

Other issues we dealt with as we encountered. For example, the biggest tender in our data set, issued in 2022 by the Paraná state education department to procure shark meat and other foods for 2,250 schools, had a blurry list of recipient units. We could see how many schools there were but couldn’t read their names. We therefore added 2,250 schools to our tally of units that potentially received shark meat, but couldn’t assess how many offered early childhood education. In this case, the head of the department confirmed in an email that the shark meat was procured for all 2,250 schools.

Our analysis did not extend to Brazil’s federal transparency portal. Instead, we referenced a separate analysis by Sea Shepherd, done at the same time as our investigation, that looked at federal procurements issued from 2021-2024 and found an additional 866 shark meat tenders totaling 231 metric tons of cação. Our data set of municipal and state-level shark meat tenders does not include these procurements.

Authorities discovered an illegal processing station for angelshark and other protected species in a house in Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul state, earlier this year. Image courtesy of Igor de Almeida Sema-RS.

Authorities discovered an illegal processing station for angelshark and other protected species in a house in Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul state, earlier this year. Image courtesy of Igor de Almeida Sema-RS.

Lessons learned

Many governments tout their transparency portals as evidence of transparency and accountability. But if the portals are not user-friendly, they are merely window dressing. Our experience collecting procurement data from more than 60 Brazilian municipal and state transparency portals exposed various problems, including slow loading, poor usability (limited search functions), confusing interfaces, inconsistent data, and no options to batch download data. If a journalist or researcher wants to compile data from such databases, they should make sure to allocate the time and resources needed to figure out how to deal with each portal, as such operations are often harder than they might seem.

LLMs are still unreliable when it comes to complex, multistep tasks. Our attempt to use LLMs to verify if a school offers early childhood education did not yield satisfactory results despite iterating the prompts through both chat interfaces and application programming interfaces (APIs), which translate requests between different applications. Although most results seemed accurate, hallucinations and mistakes still occurred, which could have affected the accuracy of our analysis had we used them.

We used ChatGPT Pro for one simple task, which was to understand the different acronyms in school names and whether early childhood education is offered by different school categories. We then reviewed the results and found that they were accurate.

While we were able to establish that shark meat tenders are in fact widespread in Brazil, and which government agencies and public institutions are buying and receiving shark meat, it was less clear from the portals what species of shark were being procured. The vast majority of tenders asked simply for cação, without specifying a species. This itself became a major finding in our story, as experts told us that the lack of clarity in the tender process meant endangered species could be making their way into government procurements. As we scoured the tenders, moreover, we realized that some agencies in Rio Grande do Sul state were asking for peixe anjo, which literally means “angel fish” and is a reference to threatened angelsharks (genus Squatina). This became the subject of a follow-up story. Some government officials in charge of these procurements told us they weren’t aware they were buying angelshark and they wouldn’t purchase it going forward. Some government nutritionists also told us they didn’t know cação meant shark. The word tubarão, meaning shark in Portuguese, was virtually never mentioned in these tenders.

We wrote this article and explained our methodology in detail with the hope that other journalists reporting in different states and municipalities in Brazil — and, perhaps, in other countries where shark meat consumption is known to be widespread — can replicate or adapt the approach to investigate purchases of shark meat (or other goods). If you have questions about the methodology, please get in touch with us.

Banner image: Shark meat is prepared for distribution at CEAGESP in São Paulo, the largest food warehouse in Latin America. Image by Philip Jacobson.

Mongabay shark meat exposé sparks call for hearing and industry debate