A new study shows the Bird’s Head Seascape in West Papua is a crucial nursery for juvenile whale sharks, where most sightings involved young males feeding around fishing platforms.Researchers documented 268 individuals over 13 years, with more than half showing injuries tied to human activity, raising concerns about fisheries, tourism and emerging mining pressures.Scientists warn that protecting these habitats with stricter rules and better management is essential for the survival and recovery of the endangered species.

See All Key Ideas

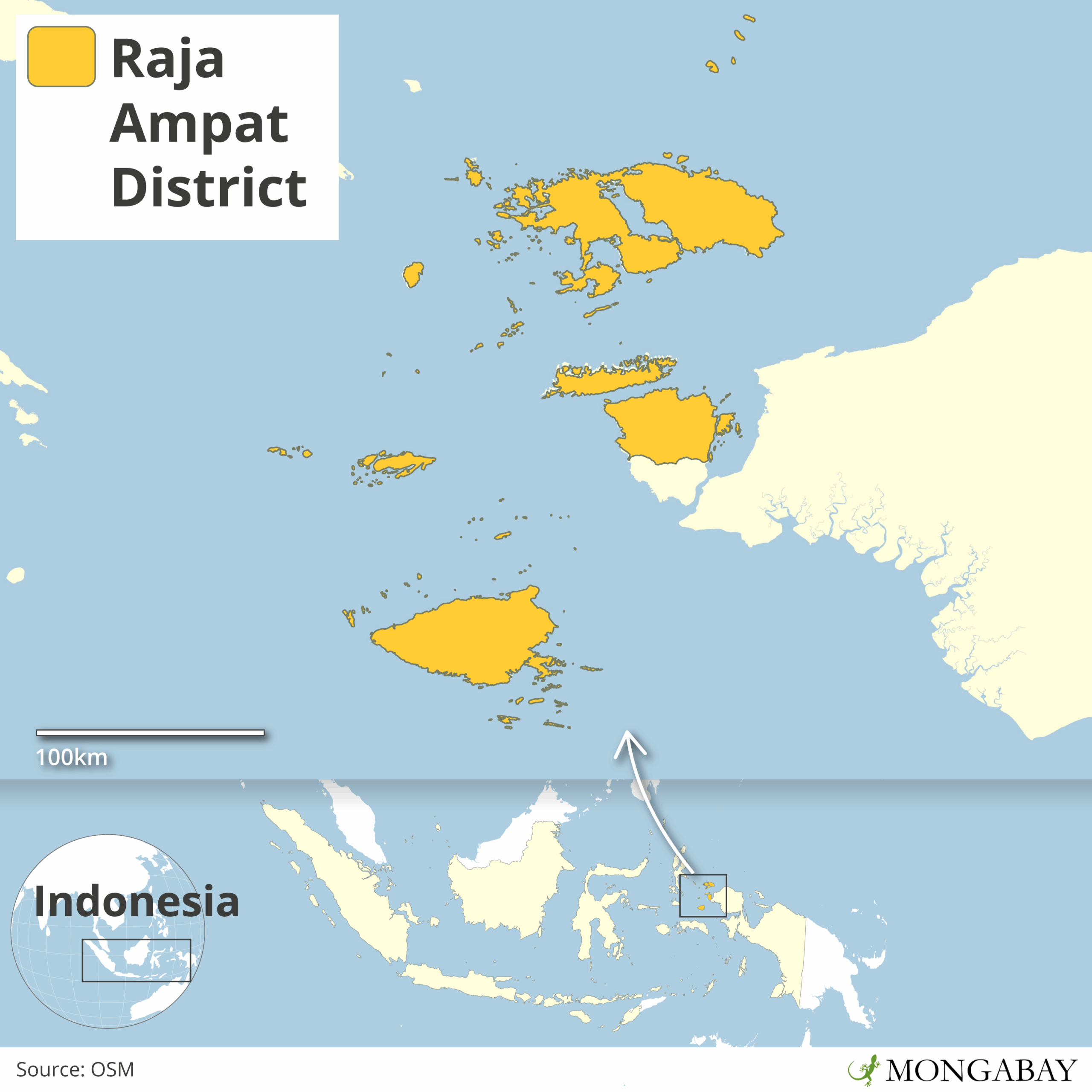

A new study reports that the Bird’s Head Seascape off Indonesia’s West Papua serves as a vital habitat for juvenile male whale sharks, but lift-net fisheries, tourism boats and emerging mining activities in the region underscore the urgent need for stronger protection and management.

The population demographics of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) within the four key BHS regions (Cendrawasih Bay, Kaimana, Raja Ampat, and Fakfak) showed a dominance of juvenile males that use these habitats as nursery or foraging grounds and reducing predation risk while growing, according to the research published Aug. 28 in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. The international group of researchers also found that more than half of the whale sharks in the study had injuries from preventable human causes.

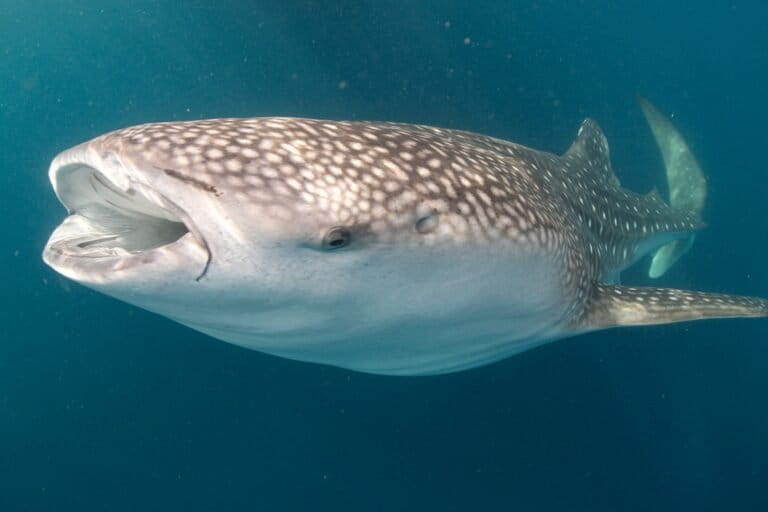

“The scars and wounds we see on whale sharks are like a diary of their encounters with people,” Edy Setyawan, lead conservation scientist at the Elasmobranch Institute Indonesia who is the lead author of the paper, told Mongabay in an email.

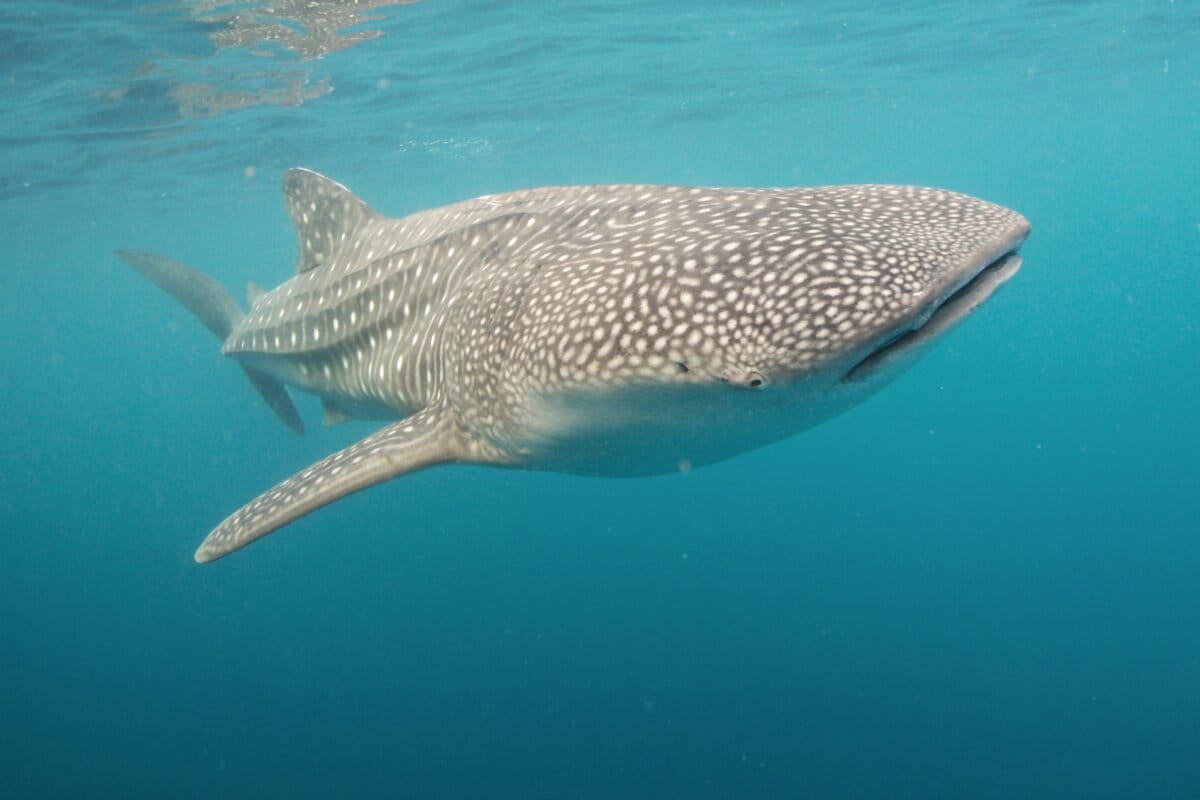

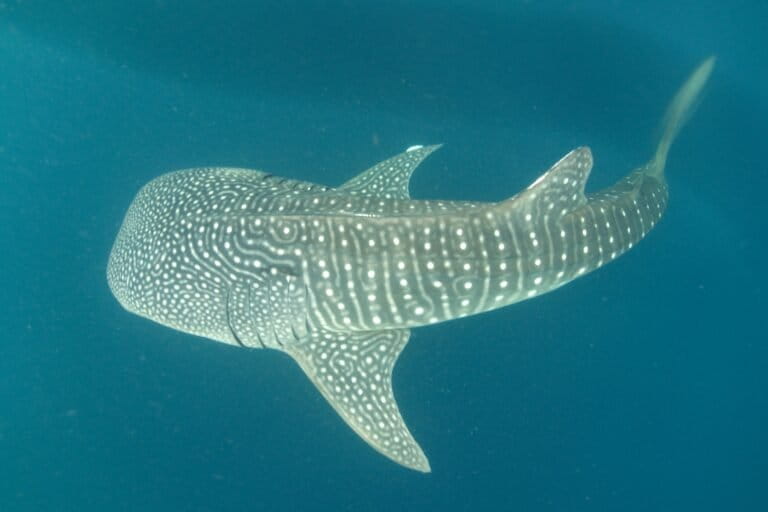

The Bird’s Head Seascape is a vital nursery for juvenile male whale sharks. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

The Bird’s Head Seascape is a vital nursery for juvenile male whale sharks. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

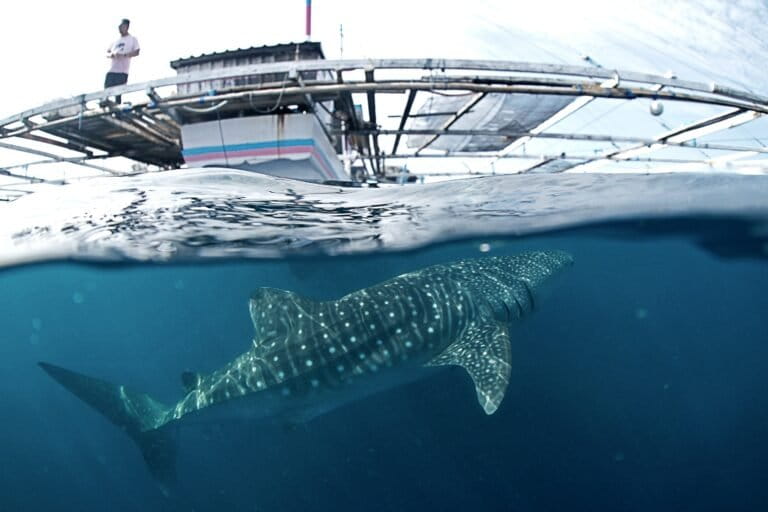

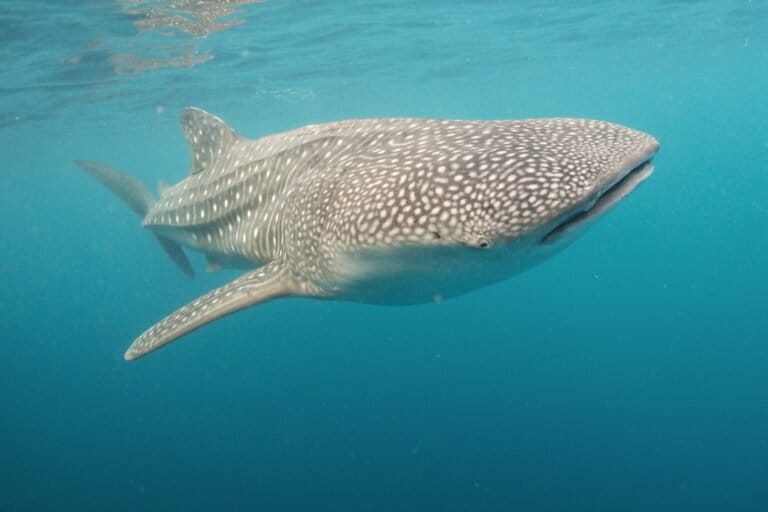

Most whale shark sightings occurred in Cenderawasih Bay and Kaimana. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

Most whale shark sightings occurred in Cenderawasih Bay and Kaimana. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

From 2010-23, the researchers tracked 268 whale sharks across the BHS — a region hosting a network of 26 marine protected areas and a hotspot for marine megafauna and tropical marine biodiversity — using photos from scientists and citizen divers. Nearly all sightings were in Cenderawasih Bay and Kaimana, where the sharks often fed around lift-net fishing platforms called bagans. Most were young males about 4-5 meters (13-16 feet) long, and more than half were spotted more than once, sometimes years apart. While many bore minor abrasions from boats and nets, serious injuries were less common but still linked mostly to human activity.

Whale sharks, the world’s biggest fish, are endangered and their numbers have dropped sharply by more than half globally and nearly two-thirds in the Indo-Pacific. They take around 30 years to reach adulthood, making it hard for populations to bounce back from threats such as hunting, habitat loss and getting caught in fishing nets. Setyawan said that every injury had a cost: It can slow them down, make feeding harder or divert energy away from growth and maturity toward healing.

“By keeping juveniles safe as they grow, we give them the chance to reach adulthood, reproduce with females and ultimately support the recovery of whale shark populations across the Indo-Pacific,” he said.

While not accounted for in the original study, the Raja Ampat archipelago is particularly facing an emerging threat of nickel mining on several of the islands, including Gag, that many experts fear will exacerbate sedimentation, pollution and potentially habitat destruction of the surrounding marine ecology. The nickel from Gag Island is shipped 250 kilometers (155 miles) to Halmahera’s Weda Bay industrial park, a hub for stainless steel and electric vehicle battery production.

Setyawan said allowing nickel mining around Gag Island in Raja Ampat to continue could threaten whale sharks by polluting waters, disrupting their food supply and adding heavy metals to the food chain. He added that increased ship traffic from mining raises the risk of collisions and disturbance. “For whale sharks, that combination means less food, poorer water quality and greater danger,” he said.

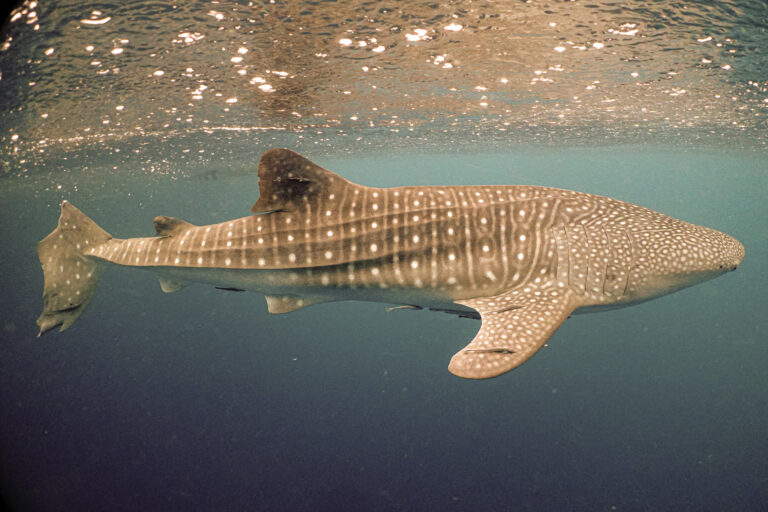

More than half of whale sharks showed injuries from human activity. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

More than half of whale sharks showed injuries from human activity. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

Whale sharks are endangered and recover slowly. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

Whale sharks are endangered and recover slowly. Image courtesy of Edy Setyawan.

The study’s authors said their findings of the whale shark demographics in the BHS should lay the groundwork for more advanced analyses (such as research of sites preferred by the females and older, sexually mature individuals) and for developing better management strategies for conservation and economic development.

For instance, Setyawan suggested stricter year-round protections, including boat speed limits, propeller guards, tourism caps and safer fishing platforms to reduce injuries in Cenderawasih Bay and Kaimana, which have high rates of whale shark residency and resighting. He added seasonal tourism closures in Cenderawasih Bay and stronger safeguards for whale shark migratory routes and feeding grounds beyond Kaimana.

“These straightforward steps can make a big difference in reducing harm to whale sharks,” Setyawan said.

Nickel mining and ship traffic pose rising threats to whale sharks. Image courtesy of Abdy Hasan/Konservasi Indonesia.

Nickel mining and ship traffic pose rising threats to whale sharks. Image courtesy of Abdy Hasan/Konservasi Indonesia.

Scientists call for stricter protections and better management of whale shark habitats. Image courtesy of Abdy Hasan/Konservasi Indonesia.

Scientists call for stricter protections and better management of whale shark habitats. Image courtesy of Abdy Hasan/Konservasi Indonesia.

Citations:

Setyawan, E., Hasan, A. W., Malaiholo, Y., Sianipar, A. B., Mambrasar, R., Meekan, M., Gillanders, B. M., D’Antonio, B., Putra, M. I. H., & Erdmann, M. V. (2025). Insights into the population demographics and residency patterns of photo-identified whale sharks Rhincodon typus in the Bird’s Head Seascape, Indonesia. Frontiers in Marine Science, 12. doi:10.3389/fmars.2025.1607027

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Follow Basten Gokkon on Twitter to see his latest work via @bgokkon.