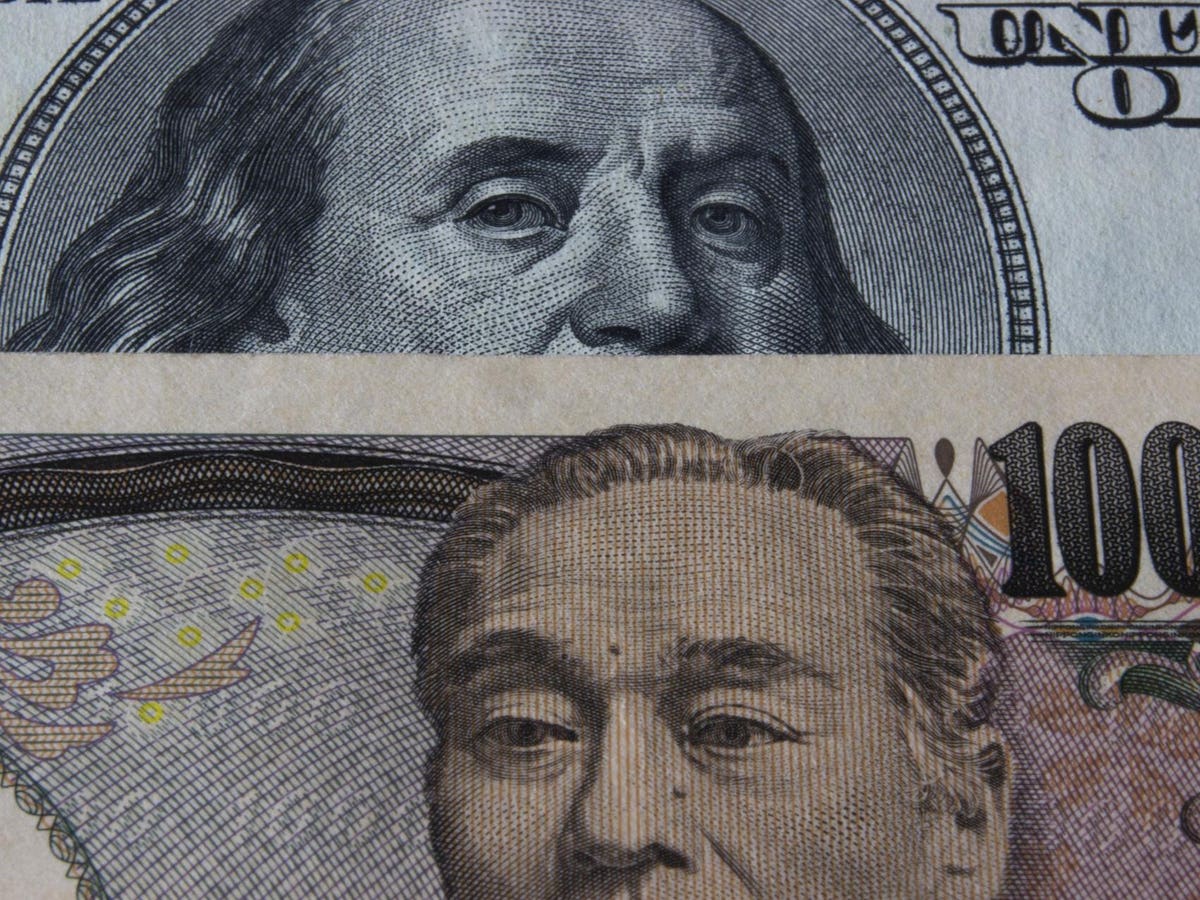

If you’re looking for another reason why the Bank of Japan won’t be hiking rates anytime soon, the number $338 trillion sure fits the bill.

That’s the debt level milestone the global economy reached in the second half of 2025. And it’s after a $21 trillion surge in the first six months of the year. Japan, not surprisingly, is one of the nations that the Institute of International Finance flags as places where “markets fear fiscal strains could deepen.”

Already, Japan has the largest debt load among developed nations, roughly 260% of gross domestic product. And, already, 20-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yields are trading near the highest since 1999.

That, of course, is the year the Bank of Japan cut its benchmark to zero — the first Group of Seven economy to do so. The return of 20-year rates to 1999 levels is a genuine problem for a nation serving such a crushing debt load.

Things are almost certain to get worse. On October 4, the Liberal Democratic Party will choose a new prime minister following Shigeru Ishiba’s resignation. Yet the only way the LDP can maintain power is to partner with pro-tax-cut opposition parties.

The specter of lower taxes deeply worries the “bond vigilantes.” In recent weeks, they sent Japanese yields 26-year highs, making global headlines for all the wrong reasons. The worry is that the biggest debt burden in the developed world is about to get even bigger.

This, of course, is a global problem. In recent weeks, investors have been betting that either the U.K. or France might need an International Monetary Fund bailout as borrowing costs get out of control. The U.S. national debt, meanwhile, has topped $37 trillion.

Japan is an example of a developed economy that’s lost the plot of growing without stimulus. Think an athlete whose performance is only thanks to steroids and other short-term enhancers. Eventually, those boosts lose potency and require bigger and bigger doses.

China is there at the moment. Asia’s biggest economy is finding that the usual fiscal and monetary bursts aren’t doing the trick in 2025 as a 5% growth pace becomes hard to sustain.

In Japan’s case, any 2% or 3% gain in GDP requires an asterisk. That’s because the growth isn’t organic or earned. It’s a product of the economic equivalent of blood doping. Thing is, how a top economy is growing matters just as much as the pace.

Two years after the BOJ first cut rates to zero, it pioneered quantitative easing. Though the U.S., U.K, the Eurozone and other top economies gave QE a try for a while, particularly after the 2008 Lehman Brothers crisis, all found an exit.

Not Japan, which remains stuck in the QE quicksand for going on 25 years now. One reason is Japan’s contribution to the earlier-mentioned $338 trillion of global debt. Each step the BOJ takes to withdraw from the bond market, an army of debt traders push back.

By 2018, the BOJ’s balance sheet was larger than Japan’s $4.2 trillion of annual output. That’s a first for a top-10 economy. And it explains why BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has shelved Tokyo’s tightening cycle.

Turns out, 0.5% is as high as Japan Inc. is collectively willing to let short-term rates go. A previous BOJ team got rates to current levels in 2007, only to cut them back to zero.

Is Ueda headed for a similar fate? Only time will tell. But the titanically large buildup in debt in Japan and everywhere else is giving central banks less and less latitude to raise rates.