Lions are more than charismatic megafauna shaping the balance of species in the savannah food web. As such, their presence or absence can tell us a lot about the health of an ecosystem.Annual lion surveys offer a disciplined way to pair concern with action, writes Jon Ayers, board chair of wild cat conservation group Panthera and major supporter of lion conservation.Such surveys do not guarantee recovery. They make it possible to know, sooner and more accurately, whether recovery is under way.This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily of Mongabay.

See All Key Ideas

On a dawn drive through a savannah reserve in Zambia, a ranger slows the truck and points to a faint trail in the dust. It is not the spoor of an antelope or a stray cow. It is the print of a lioness moving with her cubs toward a waterhole. In another era, such sightings were a matter of pride and anecdote. Today, they are data points. Each paw print, each camera image, and each confirmed pride member feeds into a growing network of annual lion surveys across sub-Saharan Africa. Those surveys are telling managers and funders something that budgets and patrol logs cannot: whether protected areas are holding their ground or slipping.

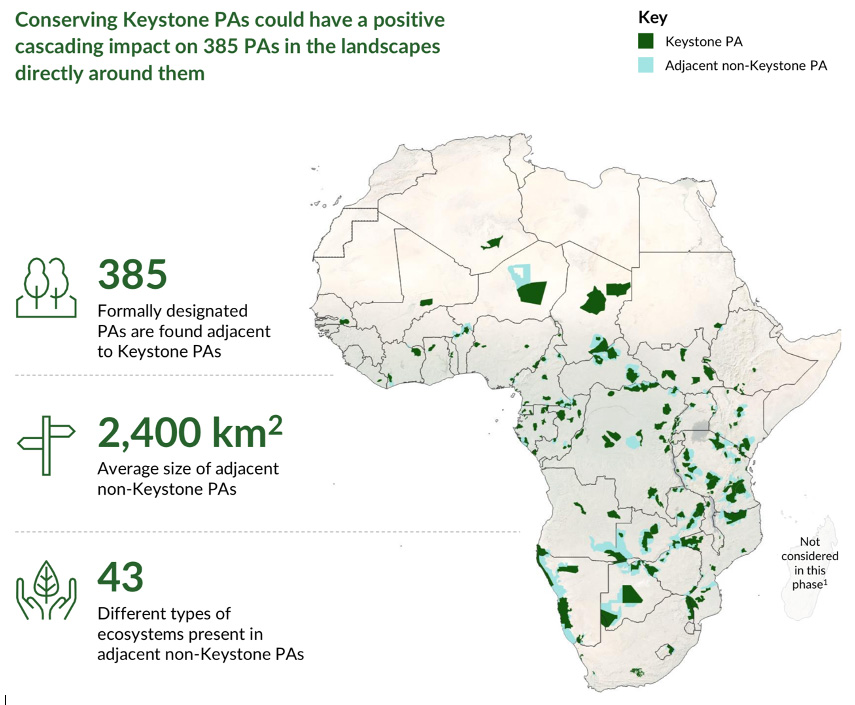

Lions are more than charismatic megafauna. They are architects of ecosystem dynamics in the savannah food web, shaping the balance of species and the landscapes they inhabit. One apex predator can influence hundreds of plant and animal species by shaping grazing pressure, predator competition, and the movement of prey. When lions vanish, the balance frays. Herbivores boom or crash, vegetation shifts, and even fire regimes change. Reintroductions rarely restore the original equilibrium. In ecological terms, the “king” is a keystone.

Lions in South Africa. Photo by Rhett Ayers Butler

Lions in South Africa. Photo by Rhett Ayers Butler

That makes lions a uniquely revealing indicator of management effectiveness. Unlike rare endemics confined to a single park, lions occur naturally in a number of Africa’s large protected areas. Unlike elephants, whose numbers can mask habitat degradation, lions decline quickly when prey is overhunted or corridors are severed. Unlike birds or insects, they are visible and countable. And unlike many metrics, a lion survey can engage communities and funders rather than bewilder them with abstractions.

The method is not guesswork. Over the past decade, Spatially Explicit Capture–Recapture (SECR) techniques have matured into a reliable way to estimate lion abundance and density. Teams directly photograph lions and their distinct characteristics or deploy camera traps, capturing images along known travel routes, identifying and cataloging each unique lion. Statistical models then correct for detection probability and movement, producing estimates accurate enough to compare year-over-year. In well-run programs, the margin of error can be within 10 percent — enough to see trends rather than noise.

Keystone Protected Areas: https://www.wcs.org/keystone-protected-areas-in-africa This paper is the result of a research collaboration between African Parks Network, Frankfurt Zoological Society and Wildlife Conservation Society, as well as independent experts Ashley Robson and Peter Lindsey—supported by the Rob Walton Foundation. This statement is currently being validated by further work by WCS as of August 1, 2025.

Keystone Protected Areas: https://www.wcs.org/keystone-protected-areas-in-africa This paper is the result of a research collaboration between African Parks Network, Frankfurt Zoological Society and Wildlife Conservation Society, as well as independent experts Ashley Robson and Peter Lindsey—supported by the Rob Walton Foundation. This statement is currently being validated by further work by WCS as of August 1, 2025.

Cost is no longer the barrier it once seemed. A properly designed SECR survey generally accounts for less than five percent of a protected area’s management budget. Managers who initially viewed it as a luxury have found it indispensable once results feed back into patrol planning, prey management, and funding proposals. Specialized lion monitoring funding facilities, such as those supported by the Lion Recovery Fund and Panthera, have catalyzed adoption by underwriting annual surveys and training local staff. Some landscapes in Kenya, Zambia, South Africa, and Senegal now conduct annual counts, creating time-series data that was unthinkable a decade ago.

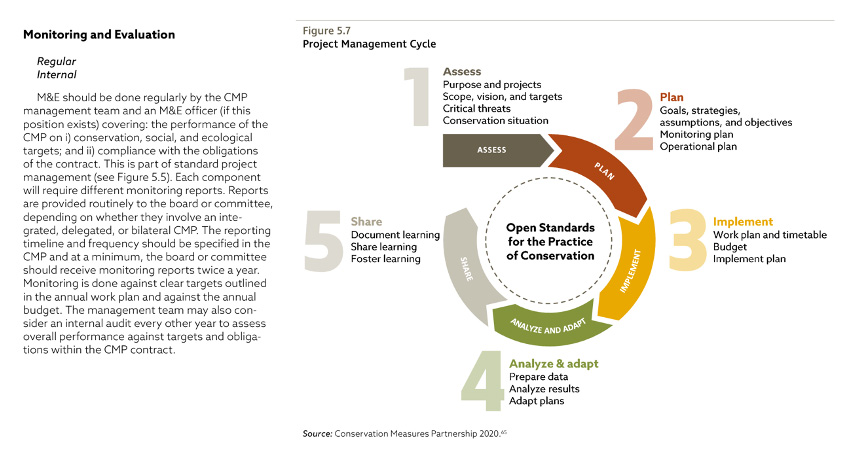

That data does more than decorate reports. It strengthens the adaptive management cycle that the World Bank’s Collaborative Management Partnership Toolkit and similar frameworks call for. Accurate lion numbers give sponsors and range states objective evidence that their investments are protecting the species that define these ecosystems. They also give managers early warning when poaching, livestock incursions, or drought push populations down. Adjustments can follow while there is still time to act.

Surveys also build local human capital. Tracking lions or setting camera traps is skilled work best done by people who know the terrain. Programs typically recruit, employ, and train local field personnel, including community members. Over successive surveys teams gain competence until the entire process — from project management to fieldwork and analysis — is handled in-country. That capacity endures beyond any single donor cycle.

For funders, the appeal is obvious. Lions command attention and imagination. They are “bankable” in a way that, say, soil invertebrates are not. A clear, affordable, repeatable metric tied to a species everyone recognizes offers a credible yardstick for conservation effectiveness. It also supplies a narrative that communities can share with visitors and officials alike: “Here is what our prides looked like last year, and here is how they are doing now.”

None of this argues against monitoring other species. Elephants, ungulates, other predators (leopards, wild dogs, and hyenas), and migratory herds matter in their own right and sometimes require different methods. But the lion stands out as an overarching indicator where it naturally occurs, and where technology and field practice have evolved to provide accurate counts. In mixed savannah systems, knowing the status of the apex predator goes a long way toward knowing the status of the web beneath it.

Male lion. Photo by Rhett Ayers Butler

Male lion. Photo by Rhett Ayers Butler

There are caveats. Lion surveys are no panacea. They cannot substitute for habitat connectivity across parks or for the political will to enforce anti-poaching laws. In forested habitats where lions are absent, managers must choose other species indicators. Even in open savannahs, SECR requires careful design, consistent methodology, and transparent reporting to avoid misleading precision.

Yet the trend is encouraging. More and more keystone protected areas are incorporating regular SECR lion surveys. With experience, what began as an experiment becomes routine. Managers come to anticipate annual results. Funders gain confidence. Communities see their work reflected in hard numbers. And a quiet feedback loop takes shape: data informs decisions, decisions improve outcomes, and outcomes justify support.

The broader lesson is that conservation gains ground not only through new laws or new money but through better information loops. When managers know in real time how their apex predator is faring, they can adjust before declines become crises. When funders see verified trends rather than anecdotes, they can invest for the long term. When communities participate in gathering the data, they become co-authors of the story rather than its subjects.

The sight of a lioness at dawn is thrilling. But in an era of constrained budgets and mounting pressures, thrill alone is not enough. Counting kings is a way of counting the health of the realm. Done well, it can turn a symbol into a signal — and give Africa’s protected areas, and the people who defend them, a clearer path to resilience.