Gender testing will come to FIS sports. | Image: Meta AI

Gender testing will come to FIS sports. | Image: Meta AI

The International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS) announced on September 24 that its Council has approved a new eligibility policy for men’s and women’s competitions, based on the presence or absence of the SRY gene, which is located on the human Y chromosome. While FIS states that the gene-based test applies to both men’s and women’s competitions, it realistically only affects women’s competitions as it essentially means that under the new policy, only SRY-negative athletes will be eligible to compete in women’s events. There is no proposal to exclude SRY-negative athletes from competing in the men’s events.

The SRY gene is a small but decisive section of DNA found on the Y chromosome. It triggers the development of testes in embryos, which then produce male sex hormones—known as androgens—leading to male physical traits. While the Y chromosome generally indicates male biological sex, the presence or absence of the SRY gene is the key determinant of male development. Rare conditions exist in which individuals have a Y chromosome without a functional SRY gene—leading to female development—or an SRY gene present in atypical locations, such as on an X chromosome.

Gene-based genetic tests look for the SRY gene which can typically be found on the Y-chromosome. | Image: Meta AI

Gene-based genetic tests look for the SRY gene which can typically be found on the Y-chromosome. | Image: Meta AI

“This policy is the cornerstone of our commitment to protect women’s sport, and we are convinced that there is only one fair and transparent way to do that: by relying on science and biological facts.”

— Johan Eliasch, FIS President

FIS says the policy followed “a period of thorough consultation with leading experts,” including medical, genetic, and sports science authorities. The eligibility conditions are explicitly grounded in genetic criteria, specifically focusing on whether an athlete carries the SRY gene. The decision marks a shift toward codified, biological definitions of eligibility in snow sports.

Benjamin Ritchie of Team United States in action during the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup. | Image: Christophe Pallot/Agence Zoom

Benjamin Ritchie of Team United States in action during the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup. | Image: Christophe Pallot/Agence Zoom

With Council approval now secured, FIS plans to work with National Ski Associations and other stakeholders—athletes, technical committees, and medical advisors—to create a detailed implementation plan. The rollout is expected to include timelines, testing protocols, appeals processes, and privacy safeguards.

This move aligns FIS with a broader trend among international sports federations wrestling with questions of gender, fairness, and inclusion. Some other federations have adopted SRY-based or hormone-based eligibility rules, though reactions have been mixed. Critics argue that biological sex is complex and that reliance on a single gene may oversimplify human diversity. The Human Genetics Society of Australasia, for example, has cautioned that the presence of SRY alone does not invariably correlate with function or physical advantage.

The German Ski Federation (DSV) expressed its surprise at the announcement. Stefan Schwarzbach, spokesperson for the DSV, told the German Press Agency (dpa) that “the press release surprised us a bit because we had no information on this topic to date.” However, due to the lack of concrete plans, the DSV sees no grounds for taking any actions ahead of the 2025-26 World Cup season, Schwarzbach continued. There could even be legal constraints on the implementation of said gene-based gender tests. France, Spain, and Norway for example have laws that heavily restrict genetic testing for non-medical uses.

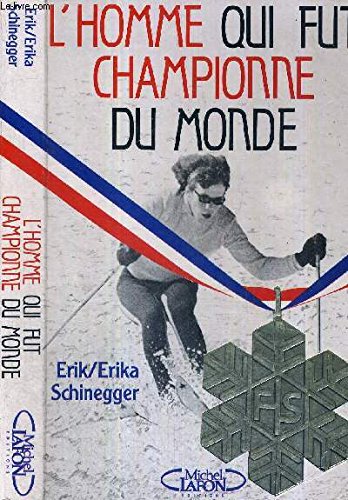

There are no publicly known cases of FIS World Cup athletes that would currently be affected under this rule. In the past, Erika Schinegger, who became the women’s downhill World Champion in Portillo, Chile in 1966, discovered during genetic testing ahead of the 1968 Olympics in Grenoble, France, that she was in fact born genetically male. Schinegger changed the first name to Erik and while he was not stripped of the medal, second-ranked Marielle Goitschel from France was awarded a gold medal retrospectively. Schinegger gave his gold medal to Goitschel, but she returned it to him after reading his autobiography, which was published in 1988. Schinegger details the struggles he faced after the discovery of his genetic gender. He suffered discrimination and prejudice for many years and could not transition to men’s alpine skiing due to the lack of acceptance of his circumstances.

Erik Schinegger’s book in French “The man who became a (female) World Champion.” | Image: Amazon

Erik Schinegger’s book in French “The man who became a (female) World Champion.” | Image: Amazon

In the coming months, FIS and national associations must map out the operational details about how and when testing will take place, the appeals mechanism for female athletes who test positive, and how to handle existing athletes whose status may change under the new rule. A successful approach must take into consideration aspects such as data privacy, consent, and counseling. The exclusion of any existing athletes could have disastrous effects for the respective athlete and needs to be handled with the utmost discretion to ensure the athletes’ dignity and privacy.