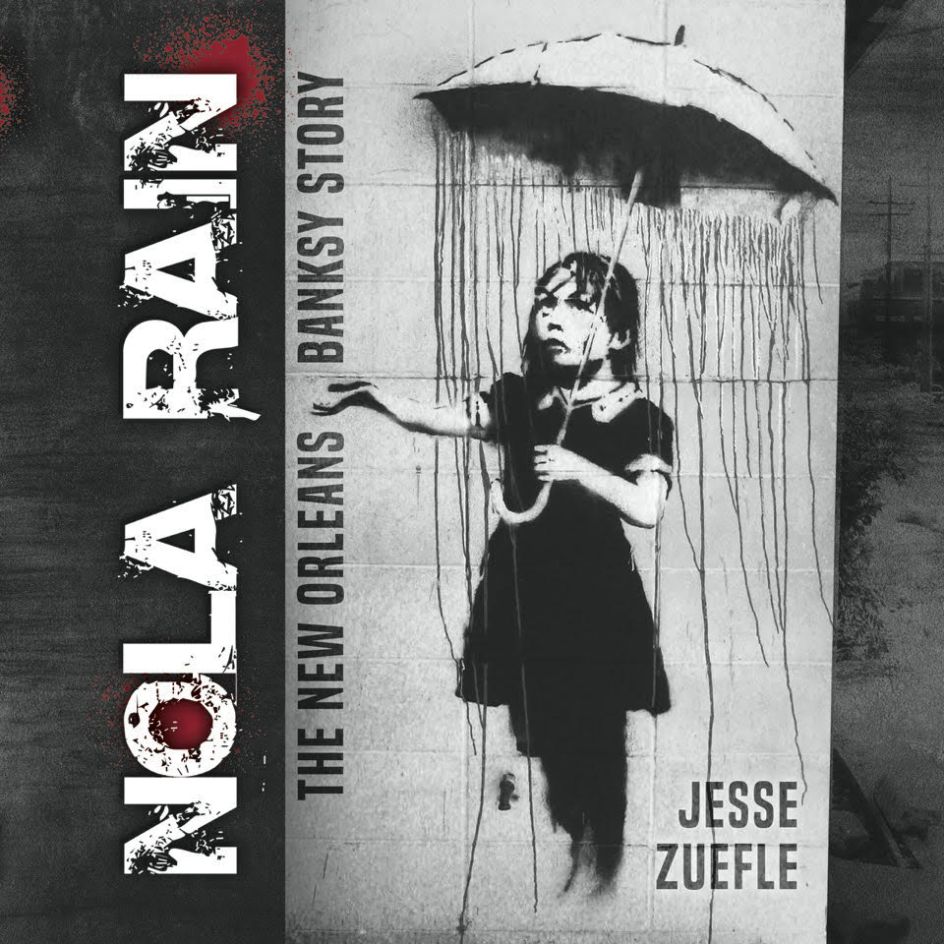

In the summer of 2008, the world’s most enigmatic street artist slipped into New Orleans like a ghost. Three years after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city, commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy, Banksy left behind 17 murals: a visceral commentary on government failure and human resilience. Now, NOLA RAIN: The New Orleans Banksy Story, by Jesse Zuefle, offers the most comprehensive account yet of this iconic intervention.

Jesse, who operates under the street art pseudonym Banksy Hates Me, brings unique credentials to this project. For over a decade, he served as self-appointed guardian of Banksy’s Umbrella Girl mural, replacing protective plastic sheeting and cleaning off vandalism. This role set him up perfectly to unravel the complex web of stories surrounding Banksy’s Louisiana adventure.

The book arrives at a particularly poignant moment. As I explained in last month’s article The unlikely story of how Banksy’s artwork took root in New Orleans, the fate of these pieces has been as dramatic as their creation. From Ronnie Fredericks’ midnight rescue of Boy on a Life Preserver Swing to Sean Cummings’s elaborate restoration involving Italian chemistry breakthroughs, the afterlife of Banksy’s New Orleans work reads like a thriller.

The mystery deepens

Sifting the truth from the myth, though, isn’t always easy. And with refreshing honesty, the author admits upfront: “The stories you will read in this book are often hearsay. Due to the natural mystery of all things Banksy-related, verifying nearly anything has been close to impossible.”

What’s not in question, of course, is how devastated the city was by the disaster. The Lower Ninth Ward, where several pieces appeared, was among the areas worst hit by Katrina’s flooding, and this predominantly African American neighbourhood became a symbol of both government abandonment and community resilience. Treme, where Boy with Trumpet was discovered, is one of America’s oldest African American neighbourhoods and the birthplace of jazz; cultural details that underscore the symbolic weight of Banksy’s chosen locations.

But more than anything else, it’s Jesse’s decade-long stewardship of the Umbrella Girl that provides the book’s emotional core. His maintenance duties—cleaning everything from graffiti tags to human waste from the protective covering—reveal the gritty reality of preserving street art. It was a role that connected him, he notes, with “land owners, police, tourists, the homeless, art lovers, neighbours, and nosy people”; a true cross-section of New Orleans society that enriches his storytelling.

Key revelations

A 54-year-old Buffalo native, Jesse originally fell in love with the city’s “architecture and arty vibe” during a 1999 visit. In 2011, he bought a house in the Marigny neighbourhood and began creating his own Banksy-inspired stencil work. His pseudonym emerged from a desire to distinguish his tribute pieces from potential counterfeits. Again, it’s a refreshingly honest approach in a field often clouded by opportunistic imitators.

Jesse’s book is packed full of intriguing detail and fascinating discoveries that will intrigue seasoned Banksy watchers. For instance, he investigates the stories behind three portraits of Abraham Lincoln that Banksy allegedly gave as gratuities to local helpers, as well as exploring the curious tale of a panel van that crashed into the building housing the Umbrella Girl; possibly in an attempt to destroy the artwork.

Most dramatically, Jesse tracks down the long-lost Boy with Trumpet piece. According to his investigation, two New York collectors flew to New Orleans in 2008 specifically to acquire a Banksy work. They allegedly pried the painting from the clapboard siding of a Treme house and transported it to Manhattan. When Jesse finally located the piece in 2024, the owners insisted he be blindfolded and surrender his phone before viewing it.

All of this drama connects to broader questions about ownership and preservation. When hotelier Sean Cummings invested significant resources in restoring Boy on a Life Preserver Swing, he framed it as preserving “public good”, making the work accessible in his hotel lobby. The contrast with this approach and the secrecy of other collectors highlights the tension between commercial exploitation and cultural stewardship.

Twenty-year perspective

Publishing NOLA RAIN to coincide with Katrina’s 20th anniversary adds historical weight to Jesse’s project. Three years after the disaster, Banksy’s 2008 visit came during a crucial period in New Orleans’ recovery, when the initial emergency response had given way to the complex work of rebuilding communities. Banksy’s murals served as both artistic commentary and an international attention grabber, forcing viewers to confront ongoing struggles largely overlooked in mainstream media coverage.

Most of the original works have now disappeared due to vandalism, demolition, or removal, making Jesse’s photographic documentation invaluable. This visual record becomes especially poignant considering that, as Jesse explains, no New Orleans Banksys survive in their original states or locations.

More broadly, this chronicle captures a pivotal moment in the evolution of street art from a subculture to a mainstream cultural force. Banksy’s New Orleans sojourn reveals a chapter that’s had scant attention on this side of the Atlantic. But for New Orleans, a city where culture serves as both an economic engine and spiritual sustenance, these interventions represented both an artistic gift and a political challenge; a legacy now preserved through the dedication of one passionate fan.