GENETIC improvement, and in particular the systems used to inform selection decisions, depend on a large way, on data collected in paddocks.

Performance records are essential as they underpin every genetic evaluation. This applies just as much to long-measured traits such as weight at 200, 400 or 600 days, as it does to harder-to-measure traits like days to calving.

While genomic technology has accelerated progress, it is important to remember that without a strong reference population the accuracy of breeding values can be constrained.

However, the importance of this data often raises a question from producers who are not producing registered cattle. That question is: “If they are collecting data on weights, fertility, or carcase traits, why can’t that information be included in genetic evaluations?”

It is not a uniquely Australian concern. Across most countries, routine evaluations rely heavily on seedstock herds. These herds provide the pedigrees, structured management cohorts and performance records that evaluation systems require. Commercial data, though potentially valuable, is not often used.

This is the focus of a recent paper published in the Journal of Animal Science by Matthew Spangler (University of Nebraska–Lincoln), Donagh Berry (Teagasc, Ireland) and Larry Kuehn (US Meat Animal Research Centre).

Single largest source of information in the industry

Their paper examined the differences in genetic recording between the US and Ireland and argued that that excluding commercial carcase data is a missed opportunity. They concluded that, in the absence of commercial data, it is dangerous to equate seedstock performance directly with a commercial situation.

They add that by dismissing the single largest source of information in the industry, accuracy is compromised and consequently true profit determinants, including fertility, longevity and adaptability are not fully accounted for.

In the US, breed evaluations are done almost solely with data from seedstock programs. This leads to a useful level of breeding values, but the lack of commercial records restricts the quantity of data.

In contrast, Ireland operates a system where every calf is tagged and recorded at birth, pedigree is verified using genomics and all data from the seedstock herd and commercial herd contributes into one national database.

This feature allows multi-breed evaluations and provides estimates of breeding values and indices of management on an across-population basis. The experience of Ireland demonstrates that it is feasible to successfully incorporate commercial data, given the suitable infrastructure and governance.

Australia’s foundation

In Australia, BreedPlan has also been built on the foundation of seedstock herds. The reliability of breeding values is due to known pedigrees, clearly identified contemporary groups and strong genetic connections that extend beyond herds. These standards are not only needed to guarantee accuracy, but they also illustrate that most commercial data cannot yet be incorporated.

In the absence of pedigree, defined cohorts or linkage by common sires, records obtained on commercial herds may lower instead of increase accuracy.

The problem is not that a need for more data; rather that data is required in a form that can meet the standards of the evaluations. Standardising data collection on common practices such as controlled joining, so that calves are comparable; weighing animals on the same day; recording management groups in a consistent manner through to using sires to create these linkages across herds are the structures that give value to data. Without them, more information – however well-intentioned – is of less value.

Potential of genomic breeding values

This does not mean commercial herds will always be excluded. Research led by Professor Ben Hayes at the University of Queensland has demonstrated the potential for genomic breeding values to be applied in commercial cattle.

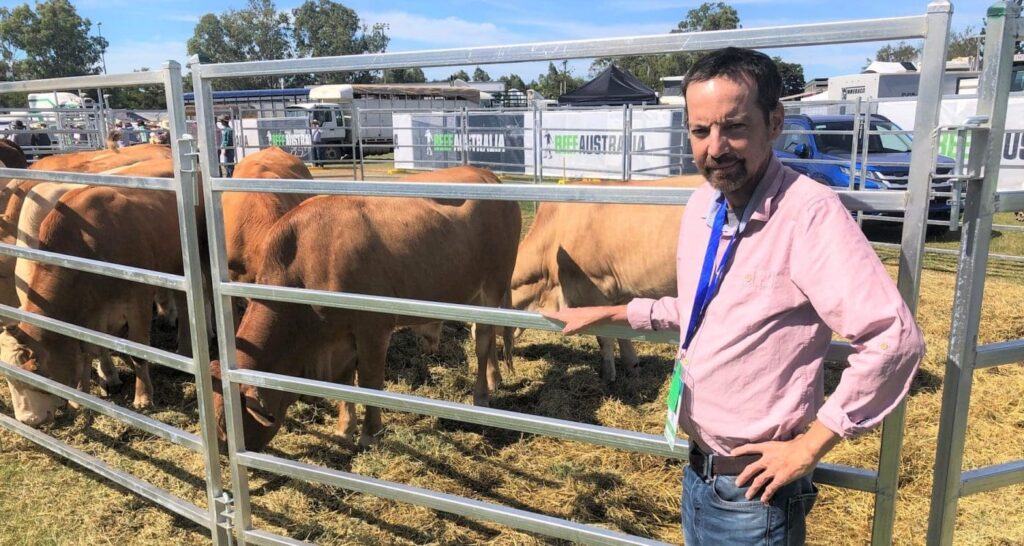

Prof Ben Hayes

By developing reference populations of genotyped and phenotyped animals, Prof Hayes (pictured at top of page, and left) and his team have shown that genomics can help fill pedigree gaps and extend evaluations into crossbred and commercial populations.

Combined with accurate on-farm performance recording, these tools provide a pathway for broader participation.

While the international research highlights the value that commercial data could add, in many cases the risks of introducing records that have not been collected under strict protocols are substantial.

Without pedigrees, defined management cohorts, and genetic linkages, additional data has the potential to weaken evaluations rather than strengthen them. The research published by Spangler, Berry and Kuehn shows us that commercial herds can contribute meaningfully, but only if their data is gathered with the same discipline as seedstock herds.

That means accurate parentage, consistent performance recording, and structures that allow animals to be fairly compared across herds and years.

Genetic progress will always depend on the quality of data collected in paddocks. The challenge now is to broaden the sources of that data while protecting the robustness and integrity that give breeding values their credibility.

Alastair Rayner

Alastair Rayner is Principal of RaynerAg and an Extension & Engagement Consultant with the Agricultural Business Research Institute (ABRI). He has over 28 years’ experience advising beef producers and graziers across Australia. Alastair can be contacted here or through his website: www.raynerag.com.au