Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Read more

Scientists have discovered a way to fertilise eggs made from the genetic material of human skin cells for the first time.

While the research is still in its early stages, experts said the finding could one day “transform” the understanding of infertility and miscarriage, and even pave the way for creating egg or sperm-like cells for people who have no other options.

In some cases, infertility can be caused by the body’s inability to produce healthy sperm or eggs and treatments such as IVF are ineffective in these patients unless a donor is used.

An emerging process, known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), involves reprogramming skin cells to become a type of stem cell.

This has “immense therapeutic potential” for people who have no viable eggs or sperm, researchers said.

It involves taking the nucleus – the control centre of the cell which stores its genetic material – from a patient’s own skin cells.

These are then implanted into a donor egg with its nucleus removed in a process known as somatic cell nuclear transfer.

However, cells generated in this way would cause any future fertilised egg to have too many chromosomes.

Humans typically have 46 chromosomes, organised into 23 pairs – half from the sperm and half from the egg.

Cells created using somatic cell nuclear transfer have two sets of chromosomes.

A method to remove this extra set of chromosomes has been studied in mice, but never using human cells.

To combat this, researchers in the US removed the nucleus in skin cells and implanted it in a donor egg.

To remove the extra chromosomes, they carried out a process they have called mitomeiosis.

This mimics natural cell division that causes one set of chromosomes to be discarded, leaving behind a healthy reproductive cell capable of being fertilised.

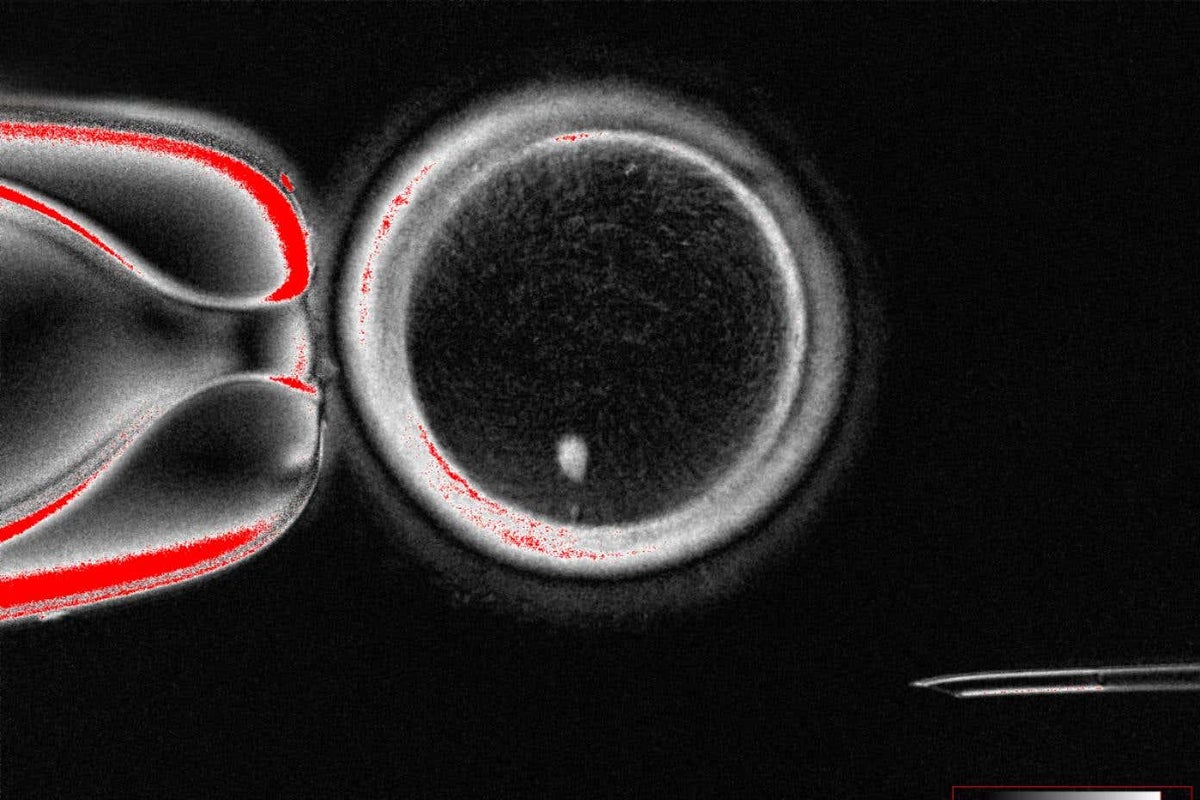

The team was able to create 82 functional developing eggs known as oocytes, which were fertilised using sperm in a lab.

Almost one in 10 (9%) of the fertilised eggs went on to develop to the blastocyst stage, which is when cells rapidly divide around six days after fertilisation.

No blastocysts were developed beyond this point, which coincides with the time they would usually be transferred to the uterus in IVF treatment.

UK experts expressed excitement at the finding but stressed further work is needed.

Ying Cheong, a professor of reproductive medicine and honorary consultant in reproductive medicine and surgery at the University of Southampton, said: “For the first time, scientists have shown that DNA from ordinary body cells can be placed into an egg, activated, and made to halve its chromosomes, mimicking the special steps that normally create eggs and sperm.

“This breakthrough, called mitomeiosis, is an exciting proof of concept.

“In practice, clinicians are seeing more and more people who cannot use their own eggs, often because of age or medical conditions.

“While this is still very early laboratory work, in the future it could transform how we understand infertility and miscarriage, and perhaps one day open the door to creating egg- or sperm-like cells for those who have no other options.”

Professor Richard Anderson, Elsie Inglis professor of clinical reproductive science and deputy director of the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, said: “Many women are unable to have a family because they have lost their eggs, which can occur for a range of reasons including after cancer treatment.

“The ability to generate new eggs would be a major advance, and this study shows that the genetic material from skin cells can be used to generate an egg-like cell with the right number of chromosomes to be fertilised and develop into an early embryo.

“There will be very important safety concerns but this study is a step towards helping many women have their own genetic children.”