Credits

Benjamin Bratton is the director of the Antikythera program at the Berggruen Institute and a professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Europe has had a conflicted relationship with modern technology. It has both innovated many of the computing technologies we take for granted — from Alan Turing’s conceptual breakthroughs to the World Wide Web (WWW) — and has also fostered some of the most skeptical and elaborate critiques of technology’s purported effects. While Europe claims to want to be a bigger player in global tech and meet the challenge of AI, its most prominent critics are quick to second-guess any practical step toward that goal on political, ethical, ecological and/or philosophical grounds.

Some policymakers envision a continental megaproject to construct a fully integrated European tech stack. But this approach is inspired by an earlier era of computational infrastructure — one based not on AI but on traditional software apps — and moreover, the political and “ethical” qualifications they also impose upon it are so onerous that the most likely outcome is further stagnation.

Lately, however, something has shifted. The wake-up calls are becoming louder and more frequent, and they have been arriving from sometimes unlikely sources. Emmanuel Macron, J.D. Vance and Berlin artist collectives may seem like unlikely allies, but they all agree that Europe’s “regulate first, build later (maybe)” approach to AI is not working. The propensity for Europe to operate this way has only resulted in greater dependency and frustration, rather than the hoped-for technological sovereignty. While Trump’s erratic approach to U.S.-European relations may be the proximate cause for the strategic shift, it is long overdue. But unless that groundswell is able to gain permanent traction in the realm of ideas, this momentum will dissipate. Given the considerable effort by tech critics across the political spectrum to prevent this progress, securing it is easier said than done.

Internet meme response to the European Union AI Act.

A “Eurostack” can be defined in different ways, some visionary and some reactionary. Italian digital policy advisor Francesca Bria and others define it as a multilayer software and hardware stack, in a plan that draws inspiration from my 2015 book, “The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty.” Specifically, it builds on a diagrammatic vision of critical infrastructure, with a stack that includes chips, networks, the variety of everyday connected items known as the internet of things, the cloud, software and a final tacked-on layer called data and artificial intelligence. This is, however, a variation of the stack of the present, not the future. My book’s “planetary computation stack diagram” will soon be republished in a 10th anniversary edition. A decade is a lifetime in the evolution of computation.

Bria’s vision is not future-facing. The European stack she proposes as a plan for the next decade should have been built 15 years ago. Why wasn’t it? Europe choked its own creative engineering pipeline with regulation and paralysis by consensus. The precautionary delay was successfully narrated by a Critique Industry that monopolized both academia and public discourse. Oxygen and resources were monopolized by endless stakeholder working groups, debates about omnibus legislation and symposia about resistance — all incentivizing European talent to flee and American and Chinese platforms to fill the gaps. Not much has changed, which is why the momentum of the moment is both tenuous and precious.

If contemporary geopolitics is leading us to think of stack infrastructure more in terms of hemispheres than nations, then unsurprisingly, the hemispherical stack of the future is built around AI — and not through the separation of AI into some “final layer” as Bria has it. Just as classical computing is different from neural network-based computation, the socio-technical systems to be built are distinct as well. This is not a radical or contentious argument, but it’s one that many prominent intellectuals fail to fully grasp. As such, it’s worth reconstructing how Europe got to where it is. The conclusion should not be that it’s too late for Europe to be a major player in the tech world, especially where AI is concerned, but rather that it will need to commit to the coming opportunities as they arise and to their implied costs.

As we’ll see, that’s easier said than done.

Merchants Of Torpor In Venice

Recently, I had the pain/pleasure of joining a panel at a conference called “Archipelago of Possible Futures” at the Venice Architecture Biennale organized by Bria and cultural researcher José Luis de Vicente, to discuss the prospects of a new Eurostack. The other panelists were two of the most well-known technology and AI skeptics, Evgeny Morozov and Kate Crawford, as well as the architect Marina Otero Verzier.

The conversation was … lively.

It was also confusing. By the end, I think I was the only one arguing that Europe should build an AI Stack (or something even better) rather than insisting that, in essence, AI is superproblematic and thus Europe should resist doing this superproblematic thing. There are many reasons for caution, including questions of power, capitalism, America, water, energy, privacy, democracy, labor, gender, race, class, tradition, indigeneity, copyright, as well as the general weirdness of machine intelligence.

“Emmanuel Macron, J.D. Vance and Berlin artist collectives may seem like unlikely allies, but they all agree that Europe’s “regulate first, build later (maybe)” approach to AI is not working.”

The maneuverable space that would satisfy all these concerns is visible only with a microscope. Remember, this was ostensibly a panel on how to actually build the Eurostack. The other panelists likely see it differently, but to me, it’s not possible to rhetorically eliminate all but a few dubious and unlikely paths to an AI Eurostack and still claim to be its advocate. That self-deception is an essential clue about Europe’s stack quandary.

During the panel, I made my case by first asking why Europe doesn’t already have the Eurostack it wants, by recounting the disappointing recent history of techno-reactionary instincts (such as anti-nuclear power politics as discussed below), the hollowness of the now orthodox critical-academic stances about AI, the problems with this approach for Europe’s plans and made a truncated plea for reason and action. In short, Europe should build AI — focusing on AI diffusion rather than solely new infrastructure — and stop auto-capitulating to elite bullies and fearful reflexes. The panel’s responses were animated, predictable and mutually contradictory.

Morozov is the author of many serious books and articles published across Europe’s left-leaning media, and therefore one of the most widely-read pundits on the dangers of American internet technologies and the need for strong “digital sovereignty” for Europe (and others). He is also the instigator of several interesting projects, including an in-depth podcast series on British cybernetician Stafford Beer’s failed Cybersyn project that was meant to govern Salvador Allende’s socialist Chile through a vast information economic matrix linking into a futuristic control center. Cybersyn was never built as it was envisioned, in reality, but it is up and running in the dreams of intellectuals in some purified alternate reality where cybersocialism runs the world. Morozov popularized the term “technological solutionism,” which, due to inevitable semantic decay, is now a term used by political solutionists to denigrate any attempt to physically transform the infrastructures of global society that demotes their own influence.

As the panel wore on and voices grew louder and more self-revealing, it became clear that Morozov does indeed want robust European AI but only on narrow, rarefied terms that resemble something like Cybersyn, and which would, in principle, sideline large private platforms, especially American ones, with whom the Belarusian émigré is still fighting his own personal Cold War.

Crawford is an Australian researcher and author, most notably of “Atlas of AI,” a book that superimposes the American culture war curriculum, circa 2020, onto the amorphous specter of global AI. She is adept with one-liners like “AI is neither artificial nor intelligent,” a statement that has been so oft-quoted in her interviews that no one stops to ask what it means. So, what does it mean? Crawford’s explanation is that “Artificial intelligence is both embodied and material, made from natural resources, fuel, human labor, infrastructures, logistics, histories, and classifications.” This is, however, exactly what the term “artificial” means. She says that AI is not actually intelligent because it works merely through a bottom-up anticipatory prediction of next instances based on global pattern recognition in the service of means-agnostic goals. Again, this is a central aspect to how “intelligence” (from humans to parrots) has been understood by everyone from William James to the predictive processing paradigm in contemporary neuroscience.

Along with visual artist Vladan Joler, Crawford is co-creator of “Calculating Empires,” a winner of the Silver Lion award at the Biennale and an ongoing diagrammatic exercise in correlation and causality confusion that purports to uncover the dark truth of what makes computational technologies possible. The sprawling black wallpaper looks like it is saying something profound, but upon more serious inspection, one discerns that it simply draws arrows from your phone to a copper mine and from a data center to the police. The work resembles information visualization but attempts to make no analytical sense beyond a quick emotional doomscroll. It is less a true diagram than stylized heraldry built of diagramesque signifiers and activist tropes freely borrowed from others’ work. Crawford’s concluding remark on this panel was that Europe has a clear choice when it comes to AI: to passively acquiesce to American techbro hegemony or to actively refuse AI. As she put it bluntly, accept or fight!

For her part, Otero, a Spanish architect teaching at Harvard and Columbia, shared her successes in helping to mobilize resistance to the construction of new data centers in Chile. When asked for her summary position, she initially, somewhat in jest, summed it up with one word: “communism.”

“If Europe builds the Eurostack that it wants — and that it says it needs — it will be because it creates space for a different culture, discourse and a theory of open and effective technological evolution.”

So there you have it. On a panel on how Europe might build its own AI Stack, we heard highlights from the last decade of an intellectual orthodoxy that has contributed upstream to a politics through which Europe talks itself out of its own future. How to build the Eurostack? Their answers are: hold out for the eventual return of an idealized state socialism, declare that AI is racist statistical sorcery, “resist,” stop the construction of data centers and, of course, “communism.” By the end, I think the panel did a very good job exploring exactly why Europe doesn’t have the Eurostack that it wants, just not in the way the organizers intended.

The Actual (Sort-Of) Existing Eurostack

What to make of this? If Europe builds the Eurostack that it wants — and that it says it needs — it will be because it creates space for a different culture, discourse and a theory of open and effective technological evolution that is neither a copy of American or Chinese approaches nor rooted in its own moribund traditions of guilt, skepticism and institutionalized critique. The “Eurostack” that results may not even be the reflection of Europe as it is, or as it imagines itself, but may rather become a means for renewal.

The answer to the oft-posed question “Why doesn’t Europe already have a Eurostack?” is that it does — sort of. Successful European AI companies do exist. For example, Mistral, based in Paris, is a solid player in the mid-size open model space, but it is not entirely European (and that’s OK!) as many of its key funders are West Coast venture capitalists and companies. Europe is also an immensely important contributor to innovation, implementation and diffusion of some of the most significant platform-scale open source software projects: Linux, Python, ARM, Blender, Raspberry Pi, KDE and Gnome, and many more. This, however, is not a “stack” but rather, as the Berggruen Institute’s Nils Gilman puts it, “a messy pile.” Crucially, the success of these open-source projects is not because they fortify European sovereignty, but rather because they are intrinsically anti-sovereign technologies, at least as far as states are concerned. They work for anyone, anywhere, for any purpose; this is their strength. This goes against the autarchist tendencies of much of European technology discourse and symbolizes the internal contradictions of the “sovereignty” discourse. Is it sovereignty for the user (anywhere, anytime access), sovereignty for the citizen (their data cozy inside the Eurozone and its passport system), or sovereignty for the polis (the right of the state to set internal policies)?

Europe’s interests and impulses are conflicted. It wants a greater say over how planetary technologies and European culture intermingle. For some, that means expunging Silicon Valley from its midst, but Europe also wants the world to use its software and adopt its values. For those who make up the latter position, the vision of the EU as a “regulatory superpower” setting the honorable rules that we all must adhere to is a tempting substitute for a sufficient, defensible geopolitical position. “Sovereignty for me, Eurovalues for thee.” For others, the hope is for Europe to get on with it and build its own real infrastructural capacity. Heckling from the front is a commentariat fixated on the social ills of AI, social media, data centers and big technology in general. For them, mobilizing endless proclamations as to why a Eurostack is preferable in theory will somehow facilitate building the very thing itself, or for others, prevent such an atrocity altogether.

Put plainly, for Europe to succeed in realizing its most impactful contributions to the planetary computational stack, it must stop talking itself out of advancement and instead cultivate a new philosophy of computation that invents the concepts needed to compose the world, not just deconstruct it or preserve it like a relic. The Eurostack-to-come cannot just try to catch up with 2025, and it cannot be manifested simply by harm-reducing legislation or by “having the conversation” about new energy sources, new chip architectures, new algorithms, new modes of human-AI interaction design, new user/platform relations, but rather by harnessing the depth of European talent to make them. Many Europeans get this and are eager to build. It’s time for European gatekeepers to get out of their own way.

I would love to see Europe build its own stack technologies — amazing new things that are impossible to conceive of or realize here in California. I am eager to use them. But as the Venice Biennale panel demonstrated, many esteemed intellectuals offer only reasons why any path to doing so would be problematic, unethical, dangerous and/or require projects to first pass ideological filters so fine-grained that they are disqualified before any progress is possible.

“Europe must stop talking itself out of advancement and instead cultivate a new philosophy of computation that invents the concepts needed to compose the world, not just deconstruct it or preserve it like a relic.”

The end result is that today the EU has AI regulation but not much AI to regulate, leaving European nations more dependent on U.S. and Chinese platforms.

This is what backfiring looks like.

How It Started

Speaking of backfiring, this isn’t the first time that Europe has found itself deeply conflicted over the development of a powerful new technology that holds both great promise and peril. Nor is it the first time that such a conflict has been motivated or distorted by prior cultural and political commitments. Europe’s cultural preservationist instincts –becoming only more acute as populations age and demographics shift–push it toward caution, and so it ultimately loses out on the benefits of the new technology while also suffering the losses brought by the chosen alternative. Unfortunately, Europe may be making many of the same errors when it comes to AI. To get to the root of the matter and to understand this as a more general disposition, we must revisit the early 1970s.

Amid a Cold War-divided Germany and cultural-political unrest across the continent, nuclear power plants were an emerging technology that promised to bring carbon emissions-free electricity to hundreds of millions of people, but not without controversy. Health and safety concerns were paramount, if not always objectively considered. Thematic associations of nuclear power with nuclear weapons, military-industrial power and with The Establishment all contributed to a psychological calculus that made it, for some, a symbol of all that must be resisted. Nowhere was this more true than in Germany, and for this they have paid a heavy price.

Remember the “Atomkraft Nein Danke” sticker? This smiling yellow message, which originated in Denmark and spread globally, was emblematic of a movement that helped define an era. West German anti-nuclear and anti-technocratic politics coalesced in the 1970s with protests against the construction of a power plant in Wyhl that drew some 30,000 people. Protestors successfully blocked the plant and from there gained momentum. In 1979, the focus turned to the United States, where an odd mix of fiction, entertainment, infrastructural mishap and groupthink defined the cultural vocabulary of post-Watergate nuclear energy politics. March of that year saw the theatrical release of “The China Syndrome”, a sensationalistic thriller about a nuclear plant meltdown and deceitful cover-ups that stars Jane Fonda as the heroic activist news reporter who sheds light on the dangers. As if right on cue, 12 days after the film’s release, the nuclear plant Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania suffered a partial meltdown in one of its two reactors. Public communications around the incident were catastrophically bad, and a global panic ensued. Nuclear energy infrastructure was now seen with even more suspicion.

In the United States, folk-pop singer Jackson Browne co-led the opposition against the use of nuclear energy reactors, organizing “No Nukes” rock mega-concerts — solidifying anti-nuclear power politics and post-counterculture yuppie-dom as interwoven visions. In Bonn, Germany, 120,000 marchers responded by demanding that reactors be shut down, and many were. The spectre of future mass deaths was a paramount concern. Surely, Pennsylvania was about to suffer a horrifying wave of cancers over the coming years. In fact, the total sum of excess cancers was ultimately tallied to be zero. (The total number at Fukushima, other than a single worker inside the plant? Also zero.) This fact did not matter much for the public image of nuclear power, then or now.

The terminology used by those opposing nuclear energy is familiar to our ears today: “technocratic,” “centralized,” “rooted and implicated in the military,” “promethean madness,” “existential risk,” “extractive,” “techno-fascist,” “toxic harms,” “silent killer,” “waste,” “technofix delusion,” “fantasy,” etc. Across visual culture, the white clouds billowing from large concrete reactors became an icon of industrial “pollution” — even though water vapor does not pollute the air. The cultural lines had been drawn.

How It’s Going

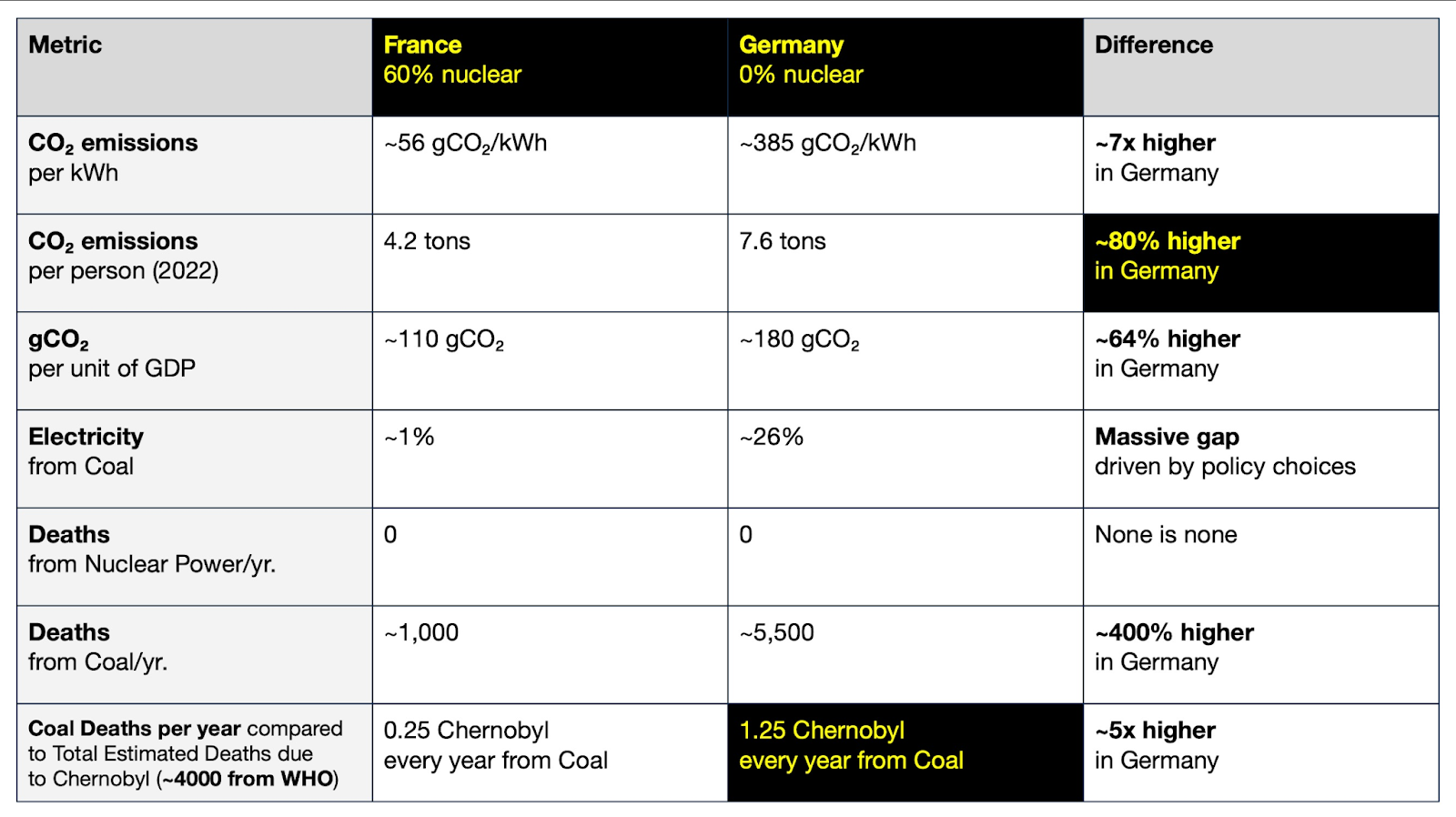

One can discern the impacts of Germany shutting down its nuclear plants for environmental, health and safety reasons by comparing it with France, which gets roughly 70% of its electricity from nuclear power. The results are stark and, spoiler alert, bad for Germany. Germany’s average CO2 emissions per kWh today are seven times higher than France’s, and its CO2 emissions per person are 80% higher. Germany turned to solar and wind (great) and oil and gas (not great) for electricity, a transformation that has had extremely negative health effects. It now gets roughly 25% of its electricity from coal (France is close to zero). Because of this disparity, Germany tolerates roughly 5,500 excess deaths from coal-related illness annually, while France’s number is closer to 1,000. That’s 450% higher.

“The same terms used to vilify nuclear power — ‘techno-fascist,’ ‘extractive,’ ‘existential risk,’ ‘Promethean madness’ and ‘fantasy’— are now regularly voiced by today’s Critique Industry to describe AI.”

One might surmise that this has nevertheless prevented the deaths from large nuclear power accidents such as Three Mile Island, Fukushima and Chernobyl. Once more, the total population deaths officially attributed to radiation-induced cancers at the first two combined add up to zero. The latter was much more serious. In 2005, the World Health Organization estimated that around 4,000 deaths were attributable to Chernobyl. Still, those deaths are less than the total number of excess coal deaths per year in Germany attributable to having shut down its nuclear power capacity.

Think about it: In order to prevent the deaths that a once-in-a-generation nuclear plant accident may cause, Germany’s Green Party-led policies inflict the equivalent of 1.25 Chernobyls per year on the population.

A comparison of the relative performance on several ecological metrics of the French nuclear baseload energy grid and German baseload energy grid that has eliminated nuclear power.

The consequences for Germany have also been political. Some of the indirect accomplishments of the anti-nuclear power, anti-megatechnology, anti-“promethean techno-fascist fantasy” movement were, for Germany, greater greenhouse gases, more deaths and more nationalist populism. Shutting down nuclear plants led to greater dependency on imported Russian oil and gas to power the economy, which in turn allowed Russia to use its ability to turn its pipelines on and off as a tool to influence Germany’s politics and charge more for energy. This has contributed to economic downturn and stagnation, which in turn has decisively helped the rise of the far-right nationalist party, Alternative für Deutschland.

What happened? A well-meaning popular movement, backed by intellectuals and influencers, motivated by technology-skeptic populism and environmental concerns, successfully arrested the development and deployment of a transnational megatechnology and ended up causing even larger direct and indirect harms.

This, too, is what backfiring looks like.

AI Nein Danke?

Two images showing different generations of a common German technopolitical subculture, each mobilized around the popular refusal of complex large-scale infrastructure, both with self-defeating consequences.

The takeaway from what happened with nuclear power would be to learn from this history and, most importantly, not do it again. Do not ban, throttle or demonize a new general-purpose technology with tremendous potential just because it also implies risk. The precautionary principle can be literally fatal. And yet that is precisely what is happening around the newest emerging technological battleground: artificial intelligence.

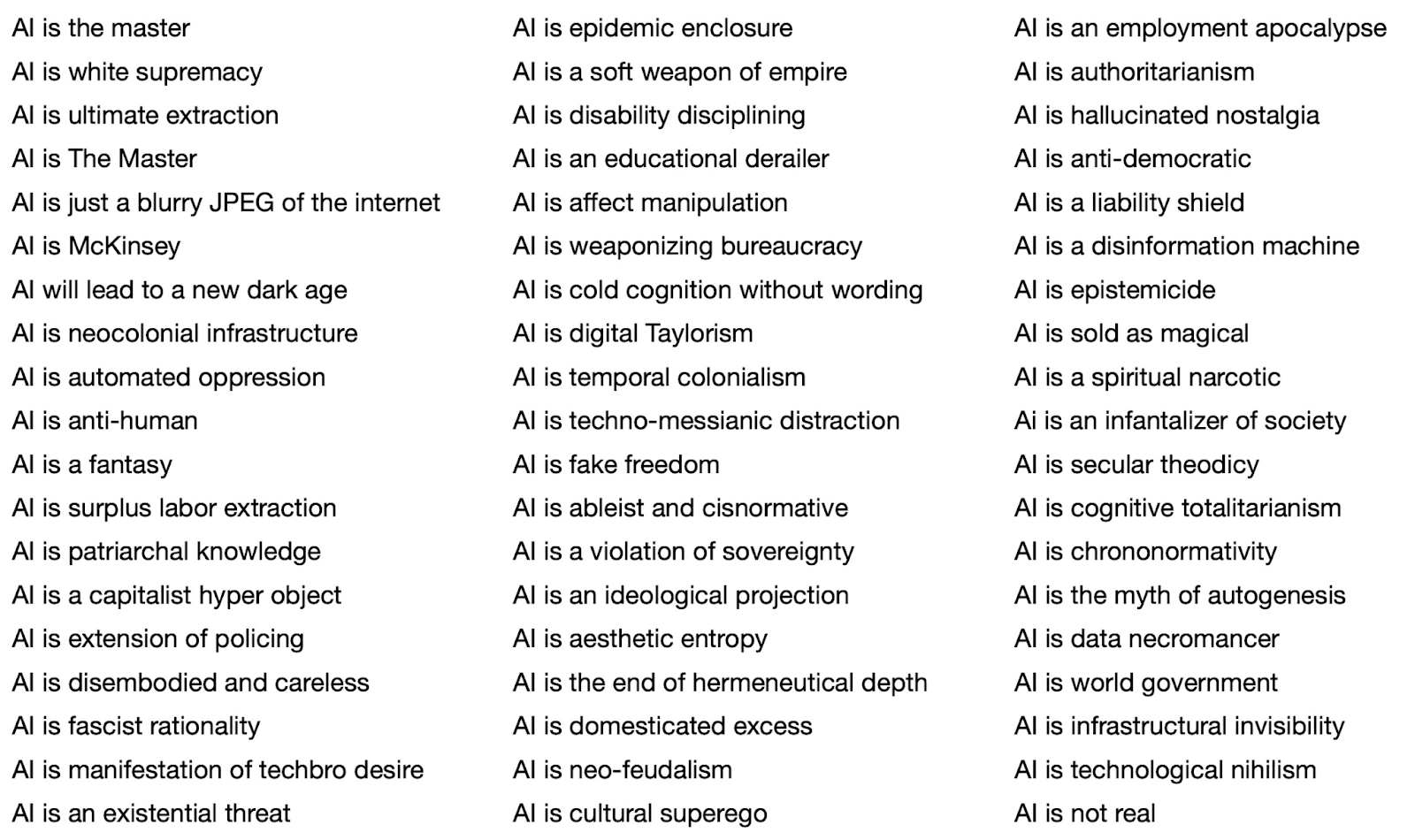

The same terms used to vilify nuclear power — “techno-fascist,” “extractive,” “existential risk,” “Promethean madness” and “fantasy”— are now regularly voiced by today’s Critique Industry to describe AI. To map the territory, I collected some of the greatest hits from contemporary academics in the humanities.

“AI is …” A representative but non-exhaustive selection of provocative characterizations of AI from contemporary Humanities books, articles and lectures. A representative index of the authors from whose work these ideas are sampled includes: Matteo Pasquenelli, Kate Crawford, Emily Bender, Alex Hanna, Dan McQuillan, Jordan Katz, Ruha Benjamin, James Poulos, Ted Chiang, Vladan Joler, Ruben Amaro, Shannon Vallor, Safiya Noble, Meredith Whitaker, Evgeny Morozov, Timnit Gebru, Byung-Chul Han, Yvonne Hofstetter, Manfred Spitzer, Gert Scobel, Nicolas Carr, Geert Lovink, Éric Sadin, James Bridle, Helen Margetts, Carole Cadwalladr, Adam Harvey, Joy Buolamwini, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Yuk Hui, and of course Adam Curtis.

Looking this over, my first thought is “Ask an academic what they think is wrong with the world and I can tell you what they think of AI.” Quite clearly, for many of them, AI seems to be not just a technology but what psychoanalysis would call a fetishized bad object. They are both repulsed and fascinated by AI; they reject it, yet can’t stop thinking about it. They don’t know how it works, but can’t stop talking about it. These statements above are less acts of analysis than they are verbalized nightmares of a 20th-century Humanism gasping for air and clawing for a bit more life.

In many cases, these eschatologies, often issued from Media Studies departments and Op-Ed pages, are not only non-falsifiable claims, but also aren’t even meant to be debated. This is Vibe Theory: an expression of elite anxiety masquerading as a politics of resistance. It is also exemplary of what the tragic ur-European philosopher Walter Benjamin once called the “aestheticization of politics,” which in this case is the result of the odd incentives that ensue when the art world makes the invitations, pays the speaker fees and publishes the essays about how culture will save us. The aesthetic power of the critical gesture is confused with reality.

More importantly, the cumulative effect of this academic consensus is not ethical rigor but general paralysis. Fear-mongering is not the way to convince people to find agency in emerging machine intelligence and incentivize creating and building. It is how a few incumbent cultural entrepreneurs try to fill the moat around their own increasingly tenuous status within institutions struggling to keep up with profound changes.

Your Personal ‘Oh Wow’ Moment

European AI should not just focus on building copycat models, but on society-scale AI diffusion, such that everyone gets to use AI for what is most interesting and important to them. But getting there is an uphill battle because, unfortunately, those who should be promoting this sort of diffusion are impeding it.

“European AI should not just focus on building copycat models, but on society-scale AI diffusion, such that everyone gets to use AI for what is most interesting and important to them.”

As a member of a faculty committee at the University of California, San Diego, I recently experienced some of the downstream effects of AI abolitionist ideas, but also how quickly the story changes when people actually use AI to do something meaningful for them. The committee has been charged with writing a statement of principles for how AI should be used in research and teaching. I was shocked by some of my colleagues’ thoughts on the matter.

Here is a sampling of (anonymous) comments I wrote down from my conversations with my university faculty: “I don’t want my students using a plagiarism machine in my class”; “The university should ban this stuff while we still can”; “It has been proven that AI is fundamentally racist”; “The techbros stole other people’s art to make a giant database of images”; “You know who likes AI? The IDF and Elon Musk, that’s who.”

Remember, these are the people responsible for determining how a top university puts these technologies to use. However, at some point in our conversations, the tide shifted. It began when a 70-year-old history professor spoke up, “I don’t know, last night I spent four hours with it talking about Lucretius. … It came up with things I had never thought of. … It was the most fun I’ve had in a long time.”

This is not atypical. Over the past several months, I have noticed a change. More and more people have told me — confiding in me as if admitting to something naughty — of a singular, interesting engagement with AI that really delighted them. They saw something they could do with AI that is important for them. They figured out how they personally could make something with AI that they could not before. After that, their opinion changed. I saw this on the faculty committee, too. A once very skeptical theater professor told me how she was now using Anthropic’s Claude to generate written score notations based on ideas for new dance performances. She was thrilled.

As of August 2025, OpenAI claimed 800 million unique users of ChatGPT per week. It’s hard to gaslight 800 million people by telling them this stuff is bogus and bad. Yet the term I have heard from some esteemed critics when presented with such moments of agency-finding is seductive. “Yes, of course, the technology is seductive.” They dismiss what you feel — wonder, curiosity and awe — and say that it is actually merely desire, and “as we all know, desire is deception.” Ultimately, this awe-shaming is paralyzing.

So What Now?

There are many reasonable ways to question my provisional conclusions, some more productive than others. Robust debate is important, but sometimes it seems as if “having the conversation” is all that Europe truly wants to do. It is excellent at this, and the necessarily global deliberation on the future of planetary computation often comes to Europe to stage itself, and for this, we should be grateful. For Europe, however, the conversation must eventually rotate into building; otherwise, it degrades into increasingly self-fortifying critique for its own sake.

Some may argue that if “critique” is exactly what is most under attack by the rise of populist nationalism, then isn’t critique what is most needed, now more than ever? Won’t the autonomy of culture lead us away from this malaise? I am doubtful. If anything, the present mode of populism and nationalism overtaking much of the world can be seen as what happens when a culture’s preferred narrativization of reality overtakes any interest in brave rationality and the sober appreciation of collective intelligence as a technologically mediated accomplishment. If populist nationalism is the “cultural determinist” view of reality in a grotesquely exaggerated mode, it is unclear why doubling down on culture’s autonomy is the obvious remedy.

Arguably, the self-defeating anti-nuclear politics of past decades were essentially a cultural commitment more than a policy position. A pre-existing cleavage between generations, classes, counter-elites, and ensuing tribal psychologies was imprinted onto the prospect of generating electricity from steam power driven by nuclear fission. In parallel, the political right’s dislike of solar power, which it views as a hippie-granola, fake solution, is based not on any real analysis of photovoltaic panel supply chains and baseload energy modeling, but rather on the fact that public infrastructure is now culturally overcoded. Maybe “culture” is another culprit, not a panacea?

“Europe has the right to put its AI under ‘democratic control’ and supervised ‘consent’ if it wants to, but it does not have a right to be insulated from the consequences of doing so.”

When extreme voices declare that Europe is “colonized” by foreign technology and must cast out the invasive species from Silicon Valley, their energy doesn’t exactly contradict the ambient xenophobia of our moment. As a placebo policy, import substitution tariffs do not work (someone please tell Trump). Autarchy is the infrastructural theory of populists, including but not exclusively autocrats. At its worst, the EU stack discourse lapses into dreams of absolute techno-interiority: “European data” about Europeans running on European apps on European hardware, perhaps even a European-only phone made solely from minerals mined west of Bucharest and east of Lisbon that runs on a new autonomous European-only cell standard and powered by a Europe-only wall plug for which by law no adapters exist. Blood and Soil and Data!

Europe surely can and should regulate the emergence of AI according to its “values,” but it must also be aware that you can’t always get what you want. Europe is free to attempt to legislate its preferred technologies into existence, but that doesn’t mean that the planetary evolution of these technologies will cooperate. If, as some economists estimate, EU AI regulations will result in a 20% drop in AI investment over the next four years, that may or may not be a good premium on digital sovereignty. It is up to Europe to decide. That is, Europe may have strong AI regulation, but this may actually prevent the AI it wants from being realized at all (again making it more reliant on American and Chinese platforms). Europe has the right to put its AI under “democratic control” and supervised “consent” if it wants to, but it does not have a right to be insulated from the consequences of doing so.

What We All Want?

In the end, it may be that all of the Venice Biennale panelists’ hopes (mine included) for what a global society mediated by strongly diffused AI looks like is more similar than different. As I put it to the panel, we might define this roughly as “a transnational socio-technological utility that is produced and served by multiple large and small organizations that provides inexpensive, reliable, always-on general synthetic intelligence and related services to an entire population who build cities, companies and cultures with this resource in an open and undirected manner, raising the quality of life and standard of living in ways unplanned and not limited by the providing organizations.” Diverse functional general intelligences on tap may have similar social implications as electricity on tap (nuclear or not) did for previous generations. More than a “tool” in and of itself, AI makes new classes of technologies possible. We should want more value to accrue through the use of a model than by the creation of the model itself. Broad riches built upon narrow riches.

So then why all the panic and misinformation? Think of it this way. What if I told you there there was a hypothetical machine that integrated the collective professional information, processes and agency that have been made artificially scarce, concentrated not just in the “Global North” but in a dozen cities and two dozen universities in the Global North, and which now makes available functional, purposive and simple access to all this through intuitive interfaces, in all languages at once, for a monthly subscription rate similar to Netflix, or even for free? This machine is less a channel for multipoint information access than a generative platform for generative agency as open as collective intelligence itself.

Would you not be suspicious of gatekeepers who demand the arrested evolution of this machine’s global diffusion because, in their words, it is not worth the electricity necessary to power it? Because it makes people dependent on centralized infrastructure or because it was developed by capitalism (and lots of publicly funded research)? Because it will transform the educational and political institutions on which democratic societies have depended, and may especially destabilize the social positions of those who have piloted those institutions? Yes, you would be right to be suspicious of them and their deeper motives, as well as the motives of their funders. You would be right to be suspicious of ideological entrepreneurs from across the political spectrum who demand to personally “audit” the models, who demand legal “compliance” to be constantly certified by political appointees, who seek to bend the representations of reality that models produce, and who seek to use them to further medievalist visions and totalitarian impulses. I hope that you are indeed suspicious of them today.

“This is a net gain for those outside of Bubbleworld but a net loss for the Ivy League (Sorry, not sorry).”

The biggest potential beneficiaries of this resource are those whose own intelligence and contributions are at present destructively suppressed by the artificial concentration of agency. They may be mostly from the same “Global South” that the gatekeepers use as a rhetorical human shield to plead their case for their own luxury belief system — affordable only to those for whom access is all they have ever known. Everywhere, the biggest benefits of on-tap functional general intelligence may accrue to individuals working outside those zones of artificially scarce agency. Large corporations already have access to a diverse range of expert agents; now so does everyone else – in principle. This is a net gain for those outside of Bubbleworld but a net loss for the Ivy League (Sorry, not sorry).

Perhaps then my goals are not the same as those of the other panelists, after all. Perhaps there is a disagreement not only about means but also about ends. Perhaps their Lysenkoist reflexes are non-negotiable, unwilling to grant that large capitalist platforms could innovate something fundamentally important, because of or in spite of their being large capitalist platforms. Perhaps the tight embrace of the conclusion that AI is intrinsically racist, sexist, colonialist and extractivist (or, for other ideologues, intrinsically woke, globalist, elitist, unnatural) is so devout that they must dismiss any evidence to the contrary, convincing themselves and their constituents not to be seduced by the reality they see before them.

Convincing people that AI is both about to destroy their culture and is also fake does not result in more agency, more universal mediation of collective intelligence, but less. The result is paralysis, lost opportunities, wasted talent and greater European dependency on American and Chinese platforms, as well as on the entrenchment of entrepreneurial tech critics defending their turf and drawing boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable alternatives.

This is what it looks like to backfire in real time.

Editor’s Note: Noema is committed to hosting meaningful intellectual debate. This piece is in conversation with another, written by Italian digital policy advisor Francesca Bria, that will be published on Thursday.