Tim Murphy was born into a working-class family in Liverpool and his parents wanted him to become a Catholic priest.

But he had different ideas and after leaving grammar school he took an admin job at the city’s stock exchange paying £2,130 a year. Over the decades, he worked his way up to eventually manage billions of pounds of investors’ money.

Now, with a seven-figure pension to his name, he believes that his life’s work is being undermined by the chancellor’s decision to charge inheritance tax on pensions from 2027.

To beat the tax trap, Murphy, 62, is giving his children £36,000 from his retirement savings each year. He said: “When I die I’m hoping the only thing that I’ll have to leave that will be taxable is my house.”

Murphy, who now lives in Kent, learnt how to trade from a colleague he knew from the company cricket team and by the time Liverpool’s trading floor closed in 1985, he had a successful career. “I went to London, Tokyo, New York. All because someone gave me a chance,” he said.

Murphy prioritised hiring young people from underprivileged backgrounds or without a university education. He remembers how, when he started, “you had to be Oxford, Cambridge, Durham or LSE yet the kids who [only] had A-levels were the hungriest people you’ve ever seen”.

• Read more money advice and tips on investing from our experts

Murphy’s achievements may be less likely now; a study in 2023 by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a research institute, found that social mobility in the UK was at its lowest in 50 years, with each generation struggling to move into higher income brackets than their parents.

Conscious of the wealth he had created, Murphy, whose father was a bus driver, spent his career carefully saving and planning the best way to pass on his legacy to his two sons. He moved from a defined benefit pension scheme, which guarantees you an income in retirement, to a more flexible self-invested personal pension (Sipp) over which he had more control.

But now he feels that he is being penalised for his success. In the October budget it was announced that pensions would be subject to inheritance tax from April 2027. Murphy decided then that there was “ no point having a pension”.

“I’m very happy paying tax at the right level, but not on something that you’ve already been taxed on.”

• Can I give my pension to the grandchildren inheritance tax-free?

Since the budget he has been giving his sons, aged 34 and 37, about £18,000 a year each from his pension pot, making use of the “gifts from surplus income” rule. Inheritance tax rules allow everyone to pass on £325,000 from their estate tax-free (£500,000 if you are leaving a main home to a direct descendant on an estate worth less than £2 million). Gifts made in your lifetime can become subject to inheritance tax if you die less than seven years after making them, but regular gifts from income (not savings or the sale of assets) can be exempt from inheritance tax if you can show that they had no effect on your standard of living. Murphy is keeping a strict record of all his transfers.

While Murphy still has to pay income tax on the pension payments that he is giving to his sons, he is still saving money by gifting it now. This is because if he died after the age of 75 and his sons were to inherit the money then, they would have to pay both income tax on their withdrawals, potentially at a higher rate, and inheritance tax on the pot.

Murphy wrote to Mike Tapp, the Labour MP for Dover and Deal, to tell him how disappointed he was. “I consider myself to be working class,” he wrote, “being brought up in Liverpool to a left-wing bus driver and stay-at-home mum, they always voted Labour.”

He told Tapp his concerns about the budget’s policies on pensions and inheritance tax. He had a reply months later. “I appreciate your concerns regarding the farming industry,” Tapp’s office wrote. “I can assure you that my commitment to farmers remains steadfast.”

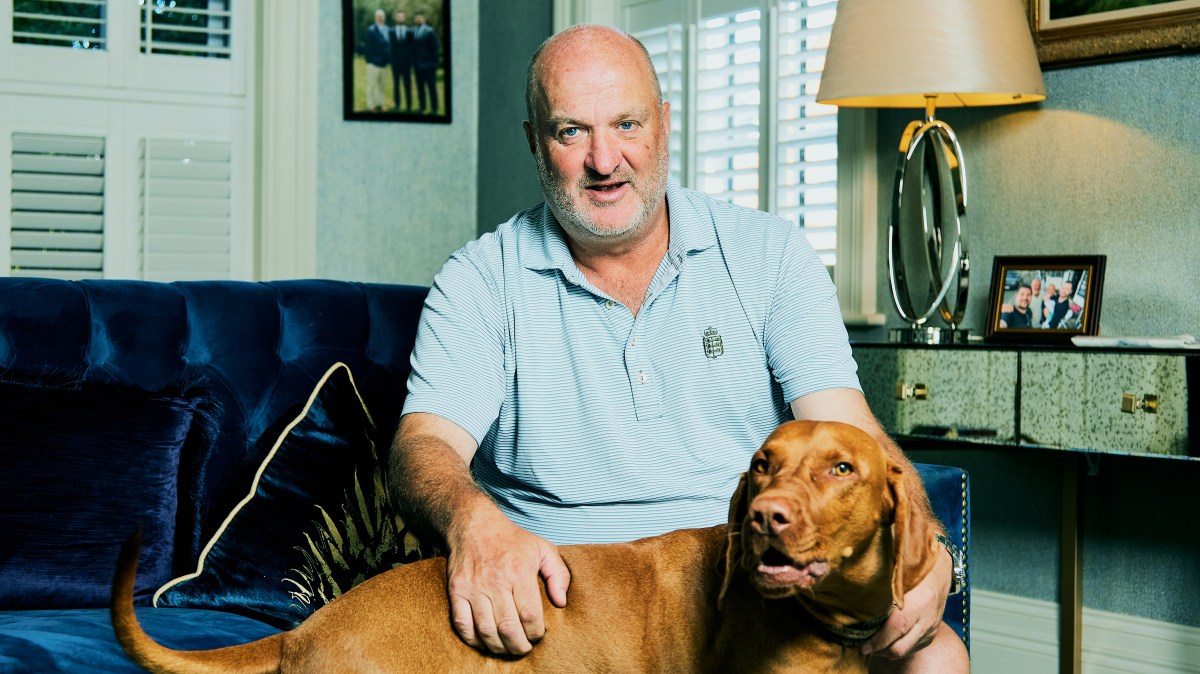

Murphy feels he is being penalised for his success

CHRIS MCANDREW FOR THE TIMES

A spokesman for Tapp apologised for the initial error but said that the MP had raised Murphy’s points “directly with Treasury ministers, and a letter was sent from a Treasury minister to Mr Murphy on March 28”.

In July, he took a tax-free lump sum from his pension pot to make a bid on a business coming up at auction. Before finalising the withdrawal, he had a letter from his investment manager reassuring him that he qualified for the 30-day “cooling-off period” in case he wanted to return the money to his pot.

After losing out on the business at auction, he decided to return the sum to his account, four days after withdrawing it. His investment manager, however, said that the rules had changed and would not allow it to be returned.

• ‘Our carefully laid financial plans are now up in the air’

“I’ve got £75,000 now sitting in a low-return interest rate environment because people don’t really know where they are and what they want to do,” Murphy said.

Craig Rickman from the wealth manager Interactive Investor said: “Consistency is so important, there needs to be a very clear message from the government. If the goalposts keep shifting, savers are understandably going to be nervous about making decisions.”

Jo Welman from the investment firm Quilter Cheviot said that sudden changes could ruin the long-term plans of diligent savers. “You’ve paid taxes on all your earnings over the decades, and you had a plan in place, and now a lot of clients are approaching retirement and all of a sudden the rules are different.”

She said that changes can discourage saving and investment. “We can’t afford to pay state pensioners but we’re disincentivising people from saving for their retirement, adding burden to the state.”

For Murphy, passing his wealth to his sons in this way had not been the plan. “I’d never intended to touch my pension at all,” he said. “I’m hoping that they invest this money themselves, but I think they’ll spend it on golf clubs.”

When interviewed for this article, Murphy said that he gave £36,000 a month from his pension to his sons. He has since been in touch to say that the correct sum is £36,000 a year. The article was amended three hours after initial publication to make this clear.