“Mind reading” often sounds like science fiction. But a new study shows it may only take a simple video.

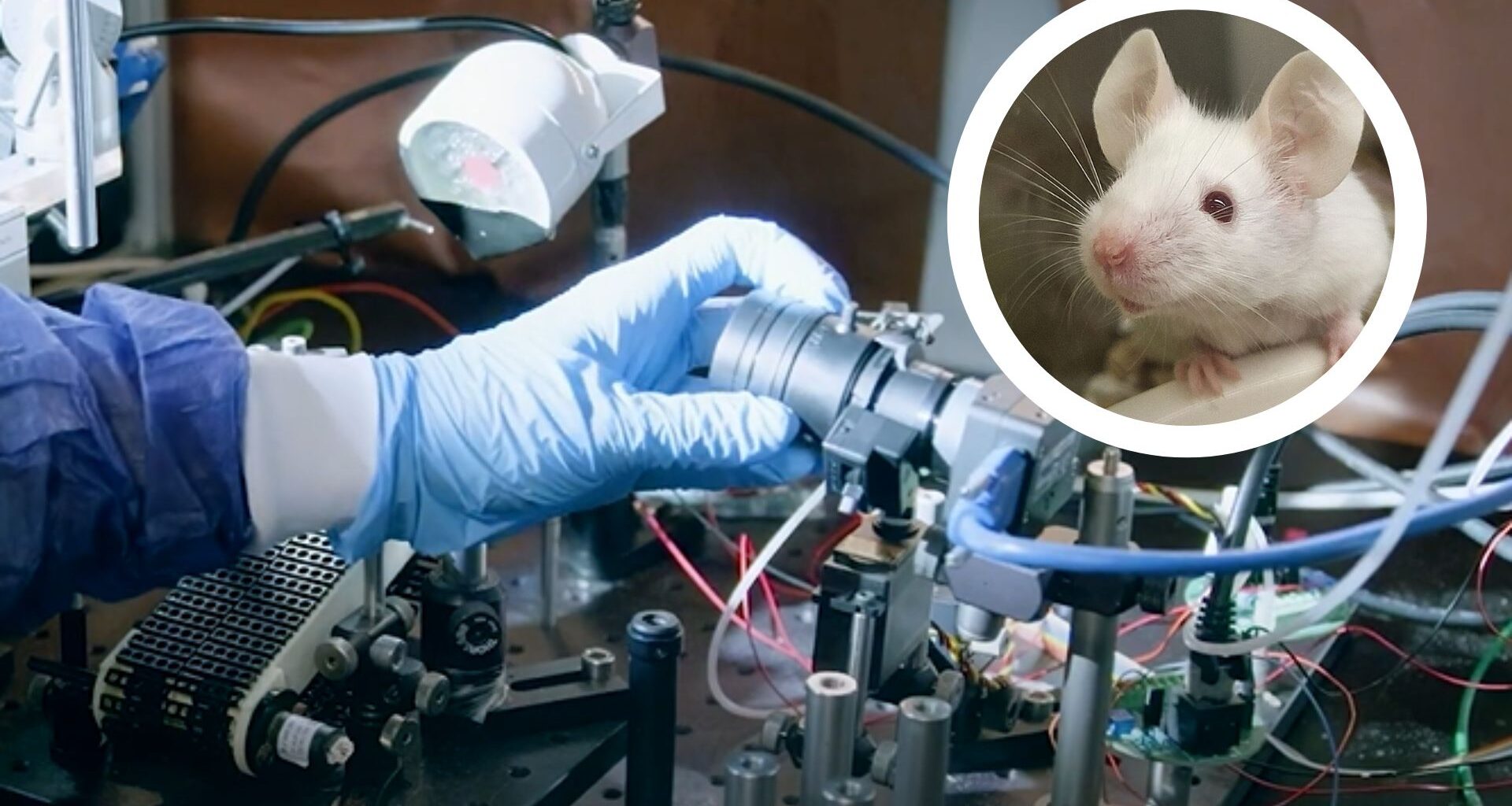

Researchers at the Champalimaud Foundation in Portugal discovered that mice’s facial movements reveal their internal thought strategies. The finding could open a non-invasive way to study brain activity while raising new concerns about mental privacy.

In earlier work, the team set up a puzzle for mice. The animals had to figure out which of two water spouts provided a sugary drink.

Since the reward switched between spouts, the mice had to adjust their strategy to get it right.

“We knew that mice can solve this task using different strategies, and we could identify which strategy they were using according to their behaviour,” said first author Fanny Cazettes, now at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Aix Marseille University.

The researchers expected neurons to reflect only the active strategy. Instead, they found all strategies represented in the brain at once, regardless of the choice made.

This prompted a new question: could those strategies also appear in the animals’ faces?

Faces mirror brain activity

The team recorded both facial movements and brain activity. They then analysed the data with machine learning. The results surprised them. Subtle facial cues proved as informative as neuron populations.

“To our surprise, we found that we can get as much information about what the mouse was ‘thinking’ as we could from recording the activity of dozens of neurons,” said Zachary Mainen, a principal investigator at the Champalimaud Foundation.

“Having such easy access to the hidden contents of the mind could provide an important boost to brain research.”

Even more striking was the consistency across animals. “Similar facial patterns represented the same strategies across different mice,” said co-author Davide Reato, now at Aix Marseille University and Mines Saint-Etienne.

“This suggests that the reflection of specific patterns of thought at the level of facial movement might be stereotyped, much like emotions.”

Promise and privacy concerns

According to the authors, the work offers a way to study brain function without invasive tools.

This could help researchers better understand health and disease. But the ease of access also raises ethical questions.

“Having such easy access to the hidden contents of the mind… also highlights a need to start thinking about regulations to protect our mental privacy,” Mainen noted.

Alfonso Renart, also a principal investigator at the Champalimaud Foundation, stressed the broader implications.

“Our study shows that videos are not just records of behaviour – they can also provide a detailed window into brain activity. Even though this is exciting from a scientific perspective, it also raises questions about the need to safeguard our privacy.”

The authors argue that facial videos may become a powerful scientific tool.

At the same time, they urge policymakers to consider safeguards before such technology moves beyond the lab.

The study is published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.