Image generated by Archinect using AI

In our latest Archinect survey, we asked architects, recruiters, and job seekers whether or not they see cover letters as valuable in the architecture job market of 2025. The response from readers exposed a range of views and divisions among job seekers and employers, and perhaps among generations. Below, we unpack your views in more detail.

Readers divided

Are cover letters still important? Earlier this month, we put this question to our readers as part of our wider study on the architecture recruitment and job-seeking process; a study headlined by our experiments on whether or not artificial intelligence could write a cover letter equal to or better than humans. According to you, it could, and it wasn’t even close.

Throughout the experiment, readers offered thoughts and reflections that went beyond AI and questioned the very function of cover letters themselves. Some told us that they detest writing cover letters and that they were cumbersome to read. Others questioned the entire purpose of cover letters, with one asking: “Who reads cover letters anymore?”

We therefore decided to step back and look at cover letters within the broader context of architectural employment in 2025. Are they valuable? Are they necessary? Are they a relic? This is what this most recent survey hoped to uncover.

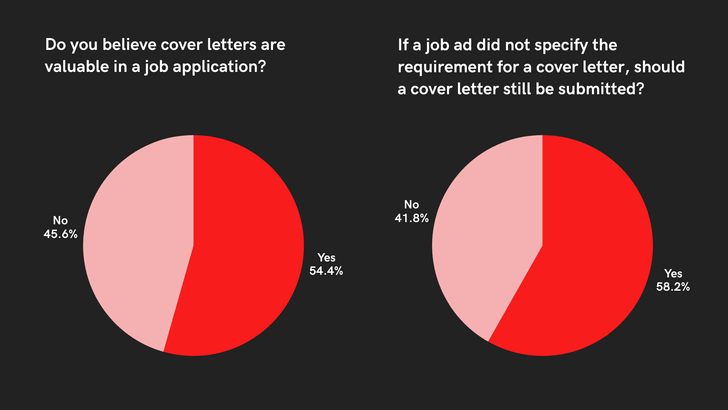

Archinect cover letter survey results, September 2025: Overall results. Image by Archinect

What we uncovered was a fractured landscape, with our community effectively split down the middle. When asked if cover letters were valuable to an architecture job application, 54% of respondents said yes, with 46% saying they were not. In parallel with our survey on Archinect’s own website, we asked our LinkedIn and Instagram audiences the same question. The results showed a similar split. On LinkedIn, 45% of respondents said cover letters were valuable, with 55% saying no. On Instagram, 56% responded yes, while 44% responded no.

The cover letter may endure not because of its utility in conveying information, but of conveying intent simply by being.

Meanwhile, our survey on Archinect’s website went further, and asked if a cover letter should still be submitted to a job ad even if the ad did not specify the requirement for one. Here, 58% said it should, while 42% said it shouldn’t.

There was, in other words, a small group of respondents who told us that even though they did not think a cover letter was valuable for a job application, one should still be included, even if not explicitly asked for. There are several reasons why this may be the case. Applicants may not want to run the risk of signalling carelessness, of ‘under-delivering’ in a competitive job market, or of being filtered out when compared to another candidate who did supply a letter. The cover letter may endure not because of its utility in conveying information, but of conveying intent simply by being.

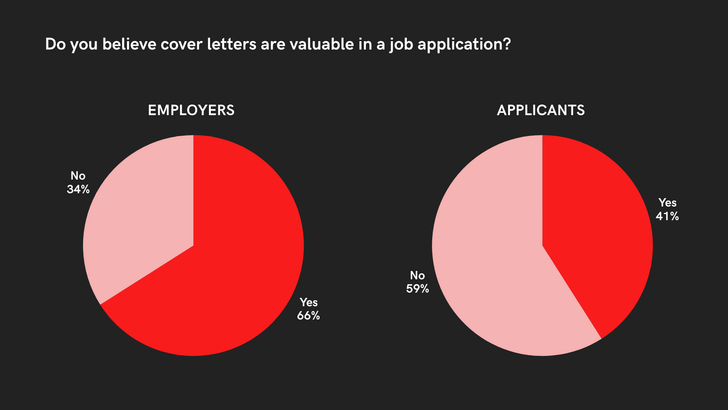

Archinect cover letter survey results, September 2025: Question 1 breakdown by employers vs applicants. Image by ArchinectEmployers vs. applicants

The discrepancies didn’t end there. The most intriguing division from our survey came when isolating the views of employers and job seekers, each of whom made up approximately 50% of survey respondents.

On the question of whether cover letters were valuable, 66% of employers and recruiters said yes, with only 34% saying no. However, only 41% of job seekers said cover letters were valuable, with 59% saying no. Employers and recruiters were therefore 25 percentage points more likely than job seekers to view cover letters as valuable.

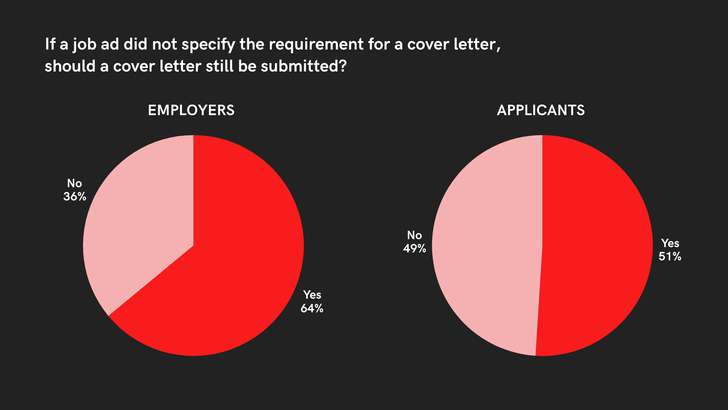

The same dynamics played out in our second question on whether a cover letter should still be submitted to a job ad even if the ad did not specify the requirement for one. Here, 64% of employers and recruiters said yes, with only 36% saying no. Job seekers were split down the middle, with 51% saying yes and 49% saying no. Employers and recruiters were therefore 13 percentage points more likely than job seekers to encourage sending a cover letter even when not requested.

Archinect cover letter survey results, September 2025: Question 2 breakdown by employers vs applicants. Image by Archinect

These divisions became clearer when respondents were asked to share their overall thoughts and reflections on cover letters. Many employers told us that a cover letter was a valuable tool for them to verify that the applicant would be a good fit for the firm, that they had good communication skills, and that they showed prior knowledge of the firm they were applying to. In an age where an applicant can send the same CV and portfolio to hundreds of firms seamlessly via email, some employers also told us they see the cover letter as a useful limiter. If an applicant must write a bespoke addressed letter to the firm, employers told us, the firm is more likely to receive applications from designers with a particular interest in the studio or its work.

“The cover letter is a chance for the candidate to tell us more about themselves in a personal way,” one employer from a large New York firm wrote in a comment that was representative of most employer respondents. “It can give context to the resume, and is an opportunity for them to say why they are interested in the firm, what they are seeking in their next position, and why they would be a strong candidate. The letter also allows us to assess written communication skills, which are still relevant with the emergence of AI.”

That said, a minority of employers did express dissatisfaction with cover letters in their current form. “Cover letters provide an additional chance to understand applicants better, yet frequently, the demand for a cover letter seems like companies merely want candidates to flatter them,” one employer told us, while another added: “Unnecessary resume padding and fluff piece is typical. Unique cover letters get attention, but generic boilerplate stuff is glossed over.”

Cover letters feel like humiliation rituals. — Survey respondent

Among job seekers, the dissatisfaction was more pronounced. While several echoed the positive notes of employers, such as cover letters offering an opportunity to introduce oneself in a more human way compared to a CV, many expressed scepticism and frustration over the role of cover letters in the hiring process.

“I think they are a holdover from another time,” one respondent wrote in a comment that captured the sentiments of many. “They were intended as an introduction to the candidate and a means of expressing interest in a position. Today, the resume and portfolio should contain concise overviews of a candidate’s experience and abilities with enough info for the employer to determine whether they want to schedule a formal interview. The interview itself is where you go into detail about your skills/experience. A cover letter is a dinosaur.”

Where some saw the cover letter as a holdover from another time, others voiced opposition to the dynamic created by job seekers writing bespoke letters to each employer, with one noting that “cover letters feel like humiliation rituals.”

“I think the whole process is just a waste of time for those who are seeking employment,” another added. “It’s truly saddening that we take our time and energy to put effort toward other people who never read our letters. It’s an unfair give and take. Why should we continue to waste our time and energy on firms that don’t read our letters? Why do we care to impress a firm that doesn’t even have the leadership quality of respect? Respect toward us, the applicants who take their time out of their lives to apply for jobs that we need to survive.”

Related on Archinect: AI Wrote a Better Cover Letter Than Me; I Don’t CareA generational shift?

Related on Archinect: AI Wrote a Better Cover Letter Than Me; I Don’t CareA generational shift?

The final quote above speaks to the inevitable power dynamic at play in the employment process, with competing applicants tasked with pitching themselves to a ‘decision-maker’ employer. To some applicants, this may indeed be a “humiliation ritual.” That same employer, however, will likewise find themselves in a frustrating scenario when pitching to a client for a commission. For every applicant asking why they should waste time and energy writing letters for firms that do not read them, there is likely an employer asking why they should waste time and energy bidding for work that doesn’t materialize.

As Archinect explored last year, frustrations over architects competing for commissions have been debated for over 100 years. The frustrations expressed through our cover letter survey, however, speak to more recent debates. Over the past five years, a new generation of designers has begun to publicly question longstanding norms within architectural labor. There are several driving factors behind this shift. Some are technological, including the impacts of social media and artificial intelligence, changing both how we communicate and organize. This technological shift will soon be the subject of an upcoming article accompanying this piece.

The 2020s have given rise to a new generation of architectural workers more naturally inclined to challenge the norms of the labor market and wider profession.

The mass move of remote work undertaken by the entire profession during the COVID-19 lockdowns should also not be underestimated as a driving force of this divide. Publications such as James Suzman’s Work: A Deep History, from the Stone Age to the Age of Robots describe how, before COVID-19, a person’s identity was deeply attached to their occupation, including in the professional services sphere that architects occupy. However, the fundamental disruption of working lives throughout the pandemic appears to have dismantled this link. A full 66% of unemployed Americans considered changing their occupation during the pandemic, a number far higher than during the 2008 recession. Even among those still employed, the raw distilling of one’s employment to eight hours in front of a home computer screen, without the frills of office gossip or socializing, caused a deep introspection over how meaningful or fulfilling our core roles and occupations really are.

As a result, the 2020s have given rise to a new generation of architectural workers more naturally inclined to challenge the norms of the labor market and wider profession. From unpaid overtime and internships to poor workplace conditions and remuneration, this generation is increasingly identifying exploitative aspects of the profession and, in response, both calling for and organizing reform.

The divide between employers and job seekers on the value of cover letters is perhaps a proxy for the divide between those who see applying for a particular job as an important step in a career that deserves time and energy, and those who are increasingly disenfranchised with the very job they use their cover letter to pitch for.