Leopard tooth marks found on the bones of our ancient ancestors reveal that humans did not rise to the top of the food chain as quickly as previously thought, a study has found.

Early humans had to survive in the wild alongside a range of fearsome beasts, including extinct creatures such as sabre-toothed tigers and dire wolves and those more familiar to us today, such as eagles, crocodiles and lions.

It was thought that the primates that existed before the evolution of the first human species were regularly preyed upon by such beasts, but that early humans, including homo habilis, became advanced enough to develop into predatory carnivores themselves. This led them to rise to the top of the food chain, learning to fend off attacks and avoid becoming dinner for other predators.

Homo habilis sharpened rocks to cut up game or scrape hides. The game would be trapped in a pit or run down by several men

BROWN BEAR/WINDMILL BOOKS/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP/GETTY IMAGES

Hyenas, lions, leopards and crocodiles remained powerful predators, but would have been seen more as competitors for food than as direct threats and may even have been hunted by humans in a reversal of the predator-prey relationship.

By two million years ago, it was thought that homo habilis had become a “dominant predator” in its environment, according to researchers from Spain and the United States.

However, a new analysis of homo habilis jawbones dating from 1.75 million years ago has identified marks left by leopard teeth.

“[This] shows leopards preyed on early humans, just as they had on earlier hominins,” researchers said. “These findings challenge the view that homo habilis had already become a dominant predator, suggesting instead that early humans were still vulnerable to large carnivores.”

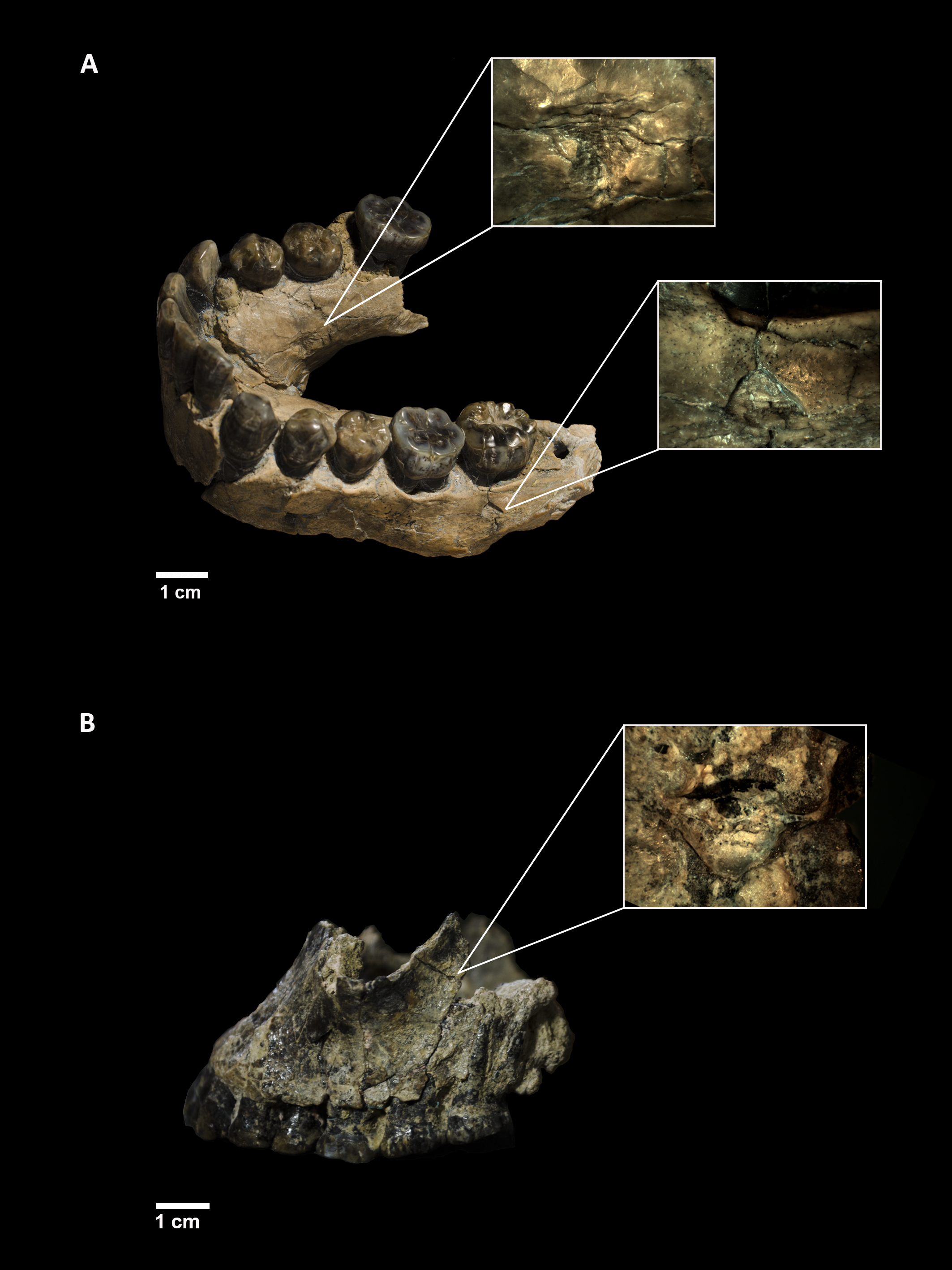

Tooth marks on the jaw bones of early humans

THE ROYAL SOCIETY

The study, published in the Royal Society Open Science journal, concluded: “Contrary to our expectations, these findings demonstrate that early Homo was still part of the prey spectrum, reinforcing the idea that the transition to dominant predator status occurred later in human evolution or [very shortly after] homo habilis through a different hominin.”

The research, led by Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo from Rice University in Texas, used artificial intelligence to analyse 1,296 tooth marks left on bones by African carnivores including leopards, hyenas, crocodiles and lions.

They applied this research to bones of homo habilis found in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. One was a lower (mandible) jawbone referred to as OH7 or Johnny’s child, thought to have belonged to a 12 or 13-year-old male. It still contains 13 teeth, plus unerupted wisdom teeth. Another was an upper (maxilla) jawbone with all of its teeth, known as OH 65, which belonged to an adult.

They found that two marks left in a mandible were “leopard-made” with a certainty of between 93.3 per cent and 99.8 per cent; while a mark left in the maxilla was also likely to have been made by a leopard gnawing on the human’s face, though with a lower probability of 53.3 per cent.

A reproduction of homo habilis in the Museum of Human Evolution in Burgos, northern Spain

CRISTINA ARIAS/COVER/GETTY IMAGES

The findings showed that the two individuals to whom the bones belonged were “preyed upon by leopards”, indicating that “felids, namely leopards, continued to be a hazard to hominins well into the early homo evolutionary stage”.

The researchers said: “It has been argued that homo habilis was responsible for the earliest episodes of stone tool-making, animal butchery, meat-eating and the reversal of the predator–prey relationship with carnivores.” However, their new findings may require a rethink of when the animal kingdom experienced a “shift in the balance of power between carnivorans and hominins”.