When Taurees Habib found out he’d won a Grammy earlier this year, he wasn’t in a tuxedo, standing under the glittering lights of the Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles. He wasn’t even watching the broadcast. Instead, he was in his kitchen, in his shorts, cooking a meal.

A friend texted him congratulations. Dune: Part Two had won in the category of Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media. That was how the first Pakistani sound engineer to ever win a Grammy, and only the second Pakistani after Arooj Aftab, discovered he’d made history. “I just wish I wasn’t standing in my kitchen, in my shorts,” he laughed, retelling the story. “But I guess that was my Grammy attire.”

For Habib, who has spent the last 13 years working alongside legendary composer Hans Zimmer on films such as Interstellar, Dunkirk, Blade Runner 2049, The Lion King, No Time To Die, Top Gun: Maverick, and both Dune films, the award was long overdue. After seven prior nominations with Zimmer’s team, the win felt almost surreal.

What he learnt through the whole process was “there’s no secret formula. The best musicians I’ve worked with all do the same thing: try something, keep it if it works, throw it out if it doesn’t. The only difference is they do that process relentlessly.”

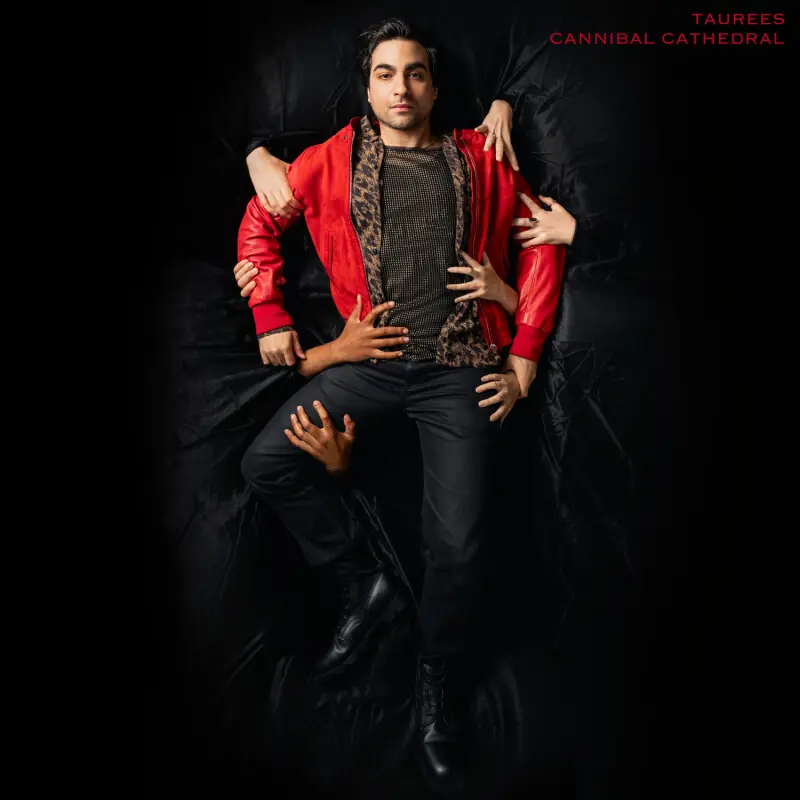

But while his Grammy has cemented his legacy as one of Hollywood’s best-kept behind-the-scenes secrets, Habib is now ready to step out front, this time under his own name. His new single ‘Cannibal Cathedral’ marks the official start of his solo career, a moody, cinematic, upbeat track that feels equal parts metal roots and something distinctly his own. A press release for the song describes it as “Trent Reznor and Alex Turner colliding inside a David Lynch fever dream”.

This isn’t his first attempt at solo work. Almost a decade ago, he put out an EP under the moniker Bedlam Jackson, even playing shows. “That was me proving to myself that I could do it all — write, record, produce, perform,” he said. But without marketing or support, it fizzled out. “I outgrew it quickly. Back then, I thought making music was enough. Now, I’ve got a team to help me actually get it heard.”

If Bedlam Jackson was proof of concept, ‘Cannibal Cathedral’ is a declaration. The song was born, fittingly, from another late-night kitchen moment in 2020, when a melody popped into his head while hunting for a snack. “I sang it into my phone immediately. That line just stuck around in my brain for years until I finally wrote it out,” he recalled. “For me, the song is about exploring your own darkness — it’s like going into the basement. Some people never come back from that, some bring something with them, and some never open that door.”

That fascination with darkness has deep roots. As a teenager in Karachi, Habib cut his teeth in the city’s underground metal scene — screaming through angst and shredding technical riffs. But he eventually grew restless. “At some point, I realised I didn’t want to just play fast or loud,” he said. “I wanted groove, mood, sexiness, something more expansive.”

One of his most formative moments came in music school, when he found himself in a “metal ensemble” with four other guitarists. “There should never be a band with four guitar players. And if it’s a metal band, even worse. It was just static because everyone was distorted and loud. I realised I was so focused on playing these complex parts that I wasn’t even listening anymore. That was the turning point.”

That expansiveness was shaped, oddly enough, by qawwali. After graduating from the Berklee College of Music, Habib returned to Karachi for eight months, studying intensively with Rauf Saami of the legendary Saami Brothers. “I hated the way my voice sounded in recordings. Training in qawwali gave me the technical control I’d been missing. I don’t think you’d hear it directly in my songs now, but it completely changed the way I sing.”

The result is a hybrid sound that sits somewhere between cinematic rock, industrial atmospherics, and an undercurrent of South Asian sensibility, not overt, but pulsing beneath the surface. It’s music that refuses to fit neatly into categories, much like Habib himself.

He is also wary of being reduced to the “Pakistani Grammy winner”. “I don’t sit down thinking, I need to do this for Pakistan. I just try to be the best version of myself, and let that speak for itself,” he explained. “For me, that’s how I represent my culture, my community — by showing up professionally, consistently, and authentically.”

He hopes the visibility he’s now getting opens doors for others. “I hope it’s not just, ‘hey, look at Taurees’ shiny new toy.’ I hope it makes people curious about where else this kind of music is happening under our noses. There’s so much incredible, eclectic music being made in Pakistan that people don’t even know about. If someone finds ‘Cannibal Cathedral’ and then goes looking for Alien Panda Jury or other local acts, that’s a win.”

And what’s next? More singles. He already has a few in the vault, written during a self-imposed isolation retreat in a mountain cabin during the Covid-19 pandemic. “Last time, I thought: I made the art, now people will just find it. This time, I want to make it easy for them to find it.”

Habib’s path has been anything but straightforward — from Karachi’s sweaty underground gigs and Berkeley College of Music to eventual qawwali lessons and Grammy gold. But as ‘Cannibal Cathedral’ signals, he’s finally stepping into the spotlight on his own terms, in his own kitchen.