Georg Baselitz has been looking back over his life. His latest exhibition, A Life in Print, is about to open at the Kode art museum in Bergen. It will prove the most comprehensive display of his printed images ever to be assembled.

How does it feel for the artist, now 87, to cast his eye back to the beginning? Does he stand by his earlier artworks? “Yes. When I see them, I think they are fantastic,” Baselitz proclaims. Germany’s art world megastar is not one for false modesty. What about his more recent pieces? Are they equally superlative? “I really morphed from a pig into a man with a tie,” he replies.

He won’t elaborate. Across the more than six decades of his career, the legendary painter has delighted in throwing the art world off balance — often quite literally. After all, he is the artist who, in his effort to “free painting from narrative” and so, escaping the “tyranny of meaning”, to thwart simple answers, became famous for painting pictures that are upside down. Images created from the late Sixties onwards have flipped on their head anything from human figures to flying eagles to pine forests. As a spectator it’s hard to avoid trying to make sense of them by twisting your head upside down. It can start off a bit of a blood rush and make you feel giddy.

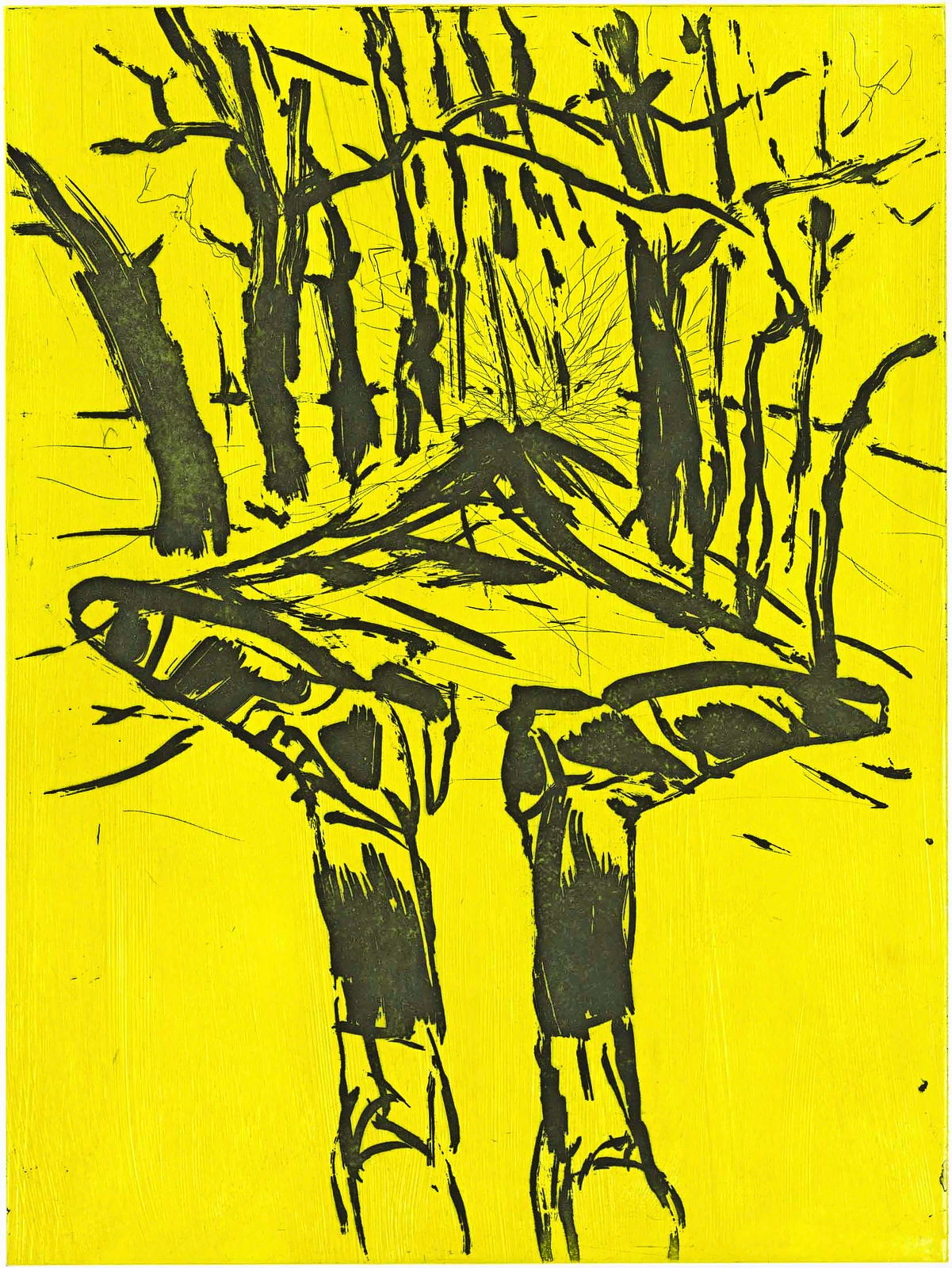

Waldweg — or “a walk in the woods”, 2004

JOCHEN LITTKEMANN

It’s hard to know quite how to approach this notoriously challenging figure. Speaking on Zoom from the book-lined study of his Salzburg home, a painting by Picasso on the wall behind him, he is sitting cross-legged, cross-armed and, to be frank, rather cross-faced. He seems annoyed by my need for someone to translate his German. Answers, as the interview goes on, grow increasingly brusque. From time to time he is stubbornly silent or offers a reply that seems intended to throw a question off course. I feel I am less meeting the man than confronting his suit of armour, which may not be surprising given the hard shell of myth that has accreted about him.

• Why I was wrong about Georg Baselitz and his upside-down paintings

Baselitz’s childhood biography has become part of his legend. Born in 1938 and named Hans-Georg Kern, he grew up in the village of Deutschbaselitz in Saxony, eastern Germany. His father, a schoolteacher, was a committed Nazi. But Hans-Georg was barely seven when the Third Reich fell. He remembers walking through the ruined streets of Dresden. He grew up amid “a destroyed order, a destroyed landscape, a destroyed people, a destroyed society”, he has said.

Expelled from art school in East Berlin for “sociopolitical immaturity” — he refused to conform to the Stalinist aesthetic of the GDR in which, by that time, he lived — he crossed to the West in 1958, three years before the wall was built. From then on he adopted the surname Baselitz, taken from his home town.

At the opening party for his exhibition at the Royal Academy with Sir Norman Rosenthal and Tracey Emin in 2007

ALAMY

It was while he was at art school in West Berlin that he discovered modernism, most dramatically in the landmark 1958 New American Painting exhibition which, showcasing the works of Pollock and De Kooning among others of the New York School, caused a sensation as it toured the cities of Europe. “It was like somebody beat me on the head with a big baseball bat,” was how he once described the experience.

You may have expected that, as with many of his contemporaries, he would have fallen into line with abstraction, or adopted the prevalent vogue for pop, or tried out the novelties of land art, or experimented with the conceptual. Instead he eschewed fashion. “I’ve never wanted to be a modern human being,” he says. “I’ve never wanted to be fashionable, to be in the time.” So although, as he says, “I’ve never met anyone who was happy to be German because of our history”, rather than trying to ignore or erase the past he did precisely the opposite.

Plunging straight back into the burnt-out ruins of his culture he confronted his German history head on. “I didn’t want to apologise for something that I had nothing to do with. I was seven when the war ended,” he says. But then, typically, he chucks a curve ball. “I was not even in the Hitler Youth … at the time I was not happy with that.”

Baselitz, at the vanguard of postwar Germany’s cultural rebirth, is considered (along with Markus Lüpertz) to be a pioneer of German neo-expressionism. Inspired by such predecessors as Max Beckmann, George Grosz and Edvard Munch, he embarked on a rough and often abrasively emotional return to paint. As a sculptor he used chainsaws and axes to hack crudely totemic figures out of lumps of wood; as a printmaker he shunned Andy Warhol’s voguish silk screens, adopting instead the rough woodcuts of his northern European ancestors. “I was once called a Kraut painter.” That, he suggests, says it all.

• Georg Baselitz: Sculptures review — I’m in awe of these raw wooden giants

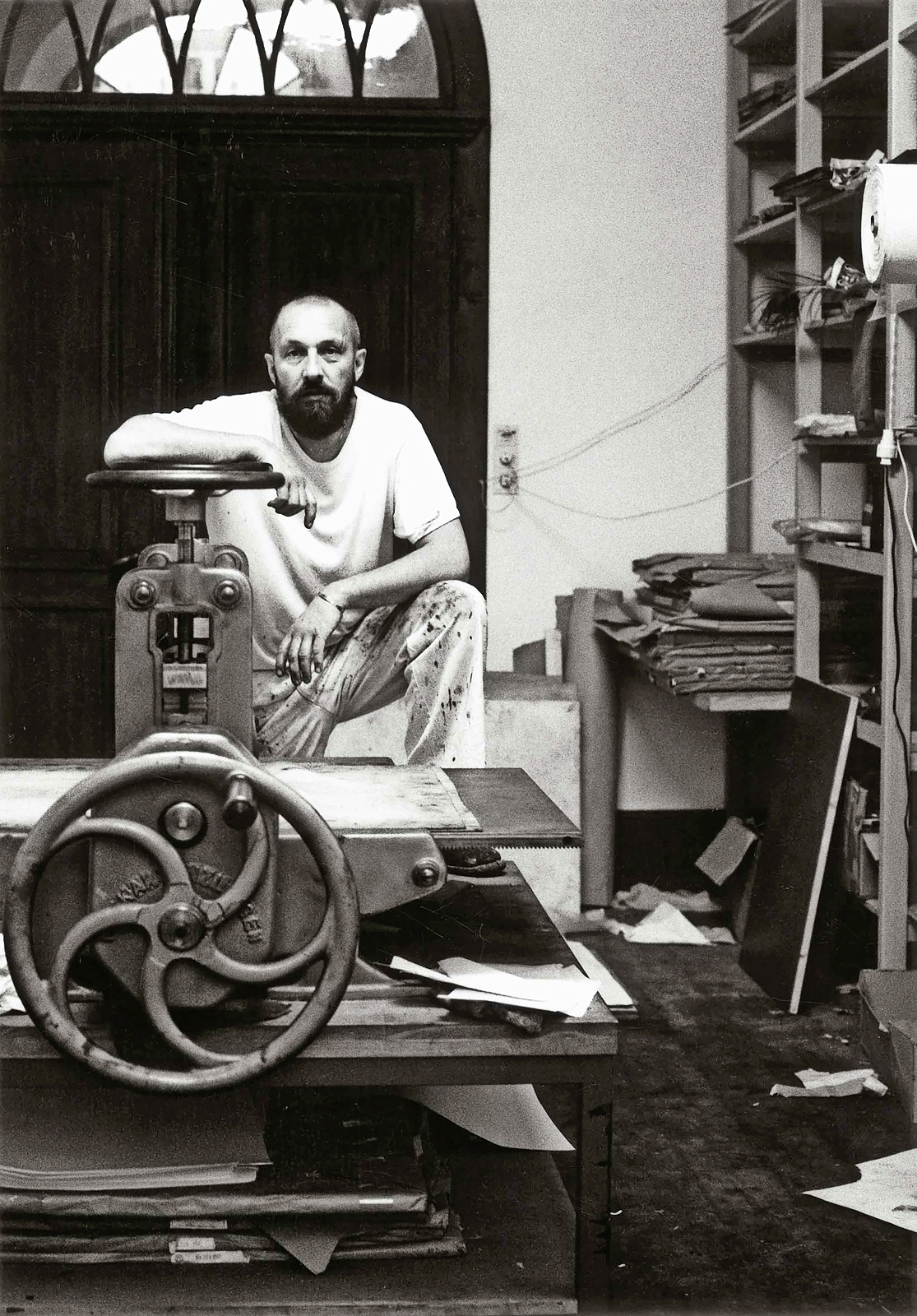

A portrait of Baselitz as he was coming to prominence in the 1960s

DANIEL BLAU/DIGITALISIERT

His images confront, inviting the spectator to see anew. “I don’t keep making works because I have sold out of the old ones,” he says. “It’s the newness of what I’m doing that interests me.”

His infamous 1963 work Big Night Down the Drain — an image to which he has returned several times — is all but magnificently repulsive. A boy with a massive head stands, stripped to the waist, against a dark background. His huge erect penis pokes, purple, from his shorts. Put on show, the work was seized by West Berlin police on suspicion of “obscenity”. Criminal proceedings ended only after two years of legal wrangling, at which point this and another impounded picture were finally returned. “Back then I thought it was unfair,” he says. “Now I almost think it’s funny.”

Was it wilfully provocative? “Not at all,” he insists. It may have made him well known, he admits, “but only with all the wrong people”. Besides, you can never predict the response to an artwork. When, 15-odd years ago, he decided for the first time to experiment with collage and started gluing pairs of nylon stockings on to his canvases, he thought, “Oh my God, people are going to react: they are so ugly. But they didn’t seem to notice at all.”

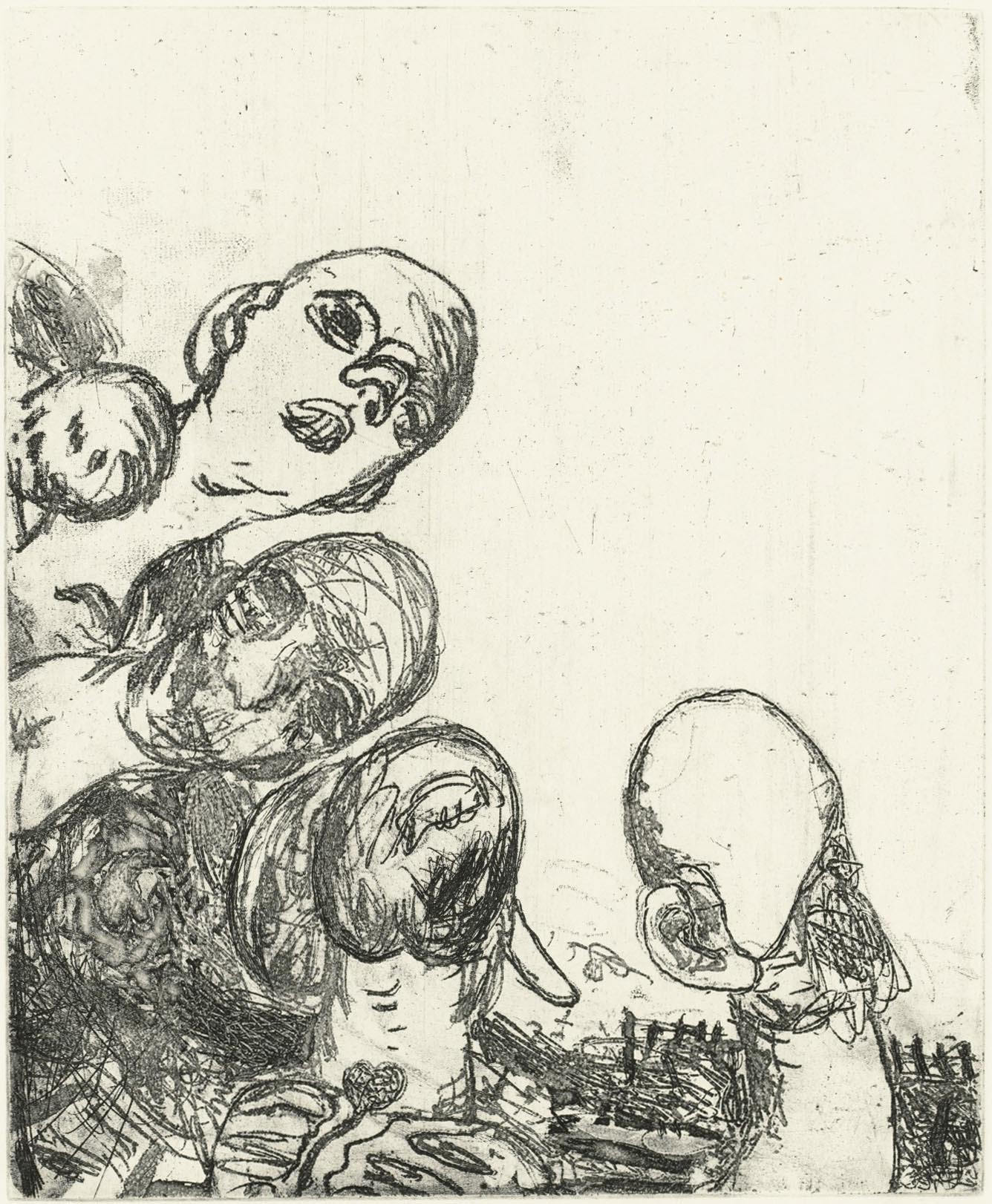

Oberon, 1964

JOCHEN LITTKEMANN

Notice was taken, however, at the 1980 Venice Biennale when his sculptures, exhibited in the German Pavilion, showed figures executing what looked like the Nazi salute. In 2015 he came under fire again for making sexist remarks in a magazine interview. “Women don’t paint very well. It’s a fact,” he apparently said, backing up his claim by declaring that women don’t pass “the market test” or “the value test”.

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

“A lot has changed since then,” he tells me, suggesting that his opinions were somewhat misrepresented. He was reacting, he implies, to a sudden faddish rush to trawl back through art history in search of overlooked female talent. “The addition of more women makes no difference,” he says. “There are good female artists and there are good male artists. The argument is about numbers.” Besides, he adds, the journalist neglected to report that “I said that Artemisia [Gentileschi] was the greatest artist of her time”.

Does he feel optimistic about the future? Sometimes, he says — but then he qualifies himself: “Sometimes I have too many depressions.” What has felt bleakest to him as he has looked back is that “nothing has changed. To enlighten myself, to try to understand life, I read thrillers like [those by the Belgian writer Georges] Simenon,” he says. “But they always have the same problems. Nothing has really changed. Only the guns have grown.”

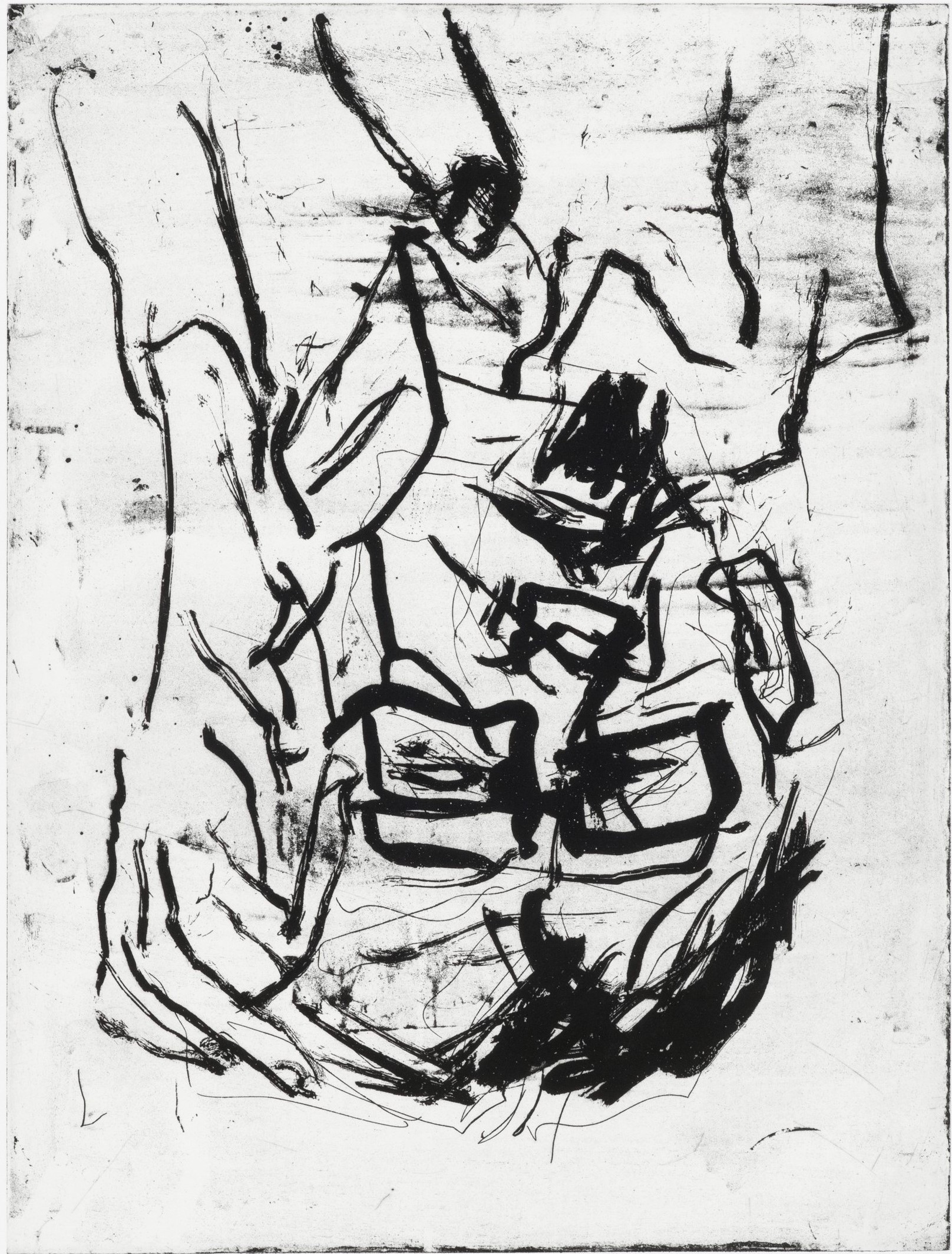

Schmidt Rottluff, 2018

COURTESY CRISTEA ROBERTS GALLERY/FXP PHOTOGRAPHY 2019

Still, Baselitz is far from ready to call it a day. It is commonly believed that the final works of great creative artists may be more mysteriously profound, more radically intransigent than anything else they have produced. Has he, as an octogenarian, reached this “late great” stage himself? “I really have thought about this,” he admits, “because I don’t want to disappear. I have looked a lot at the work of other great artists. But I haven’t reached that late stage yet.” Nor, he says, can he predict what it may be like. All he knows, he declares confidently when I ask him what, looking back over his career, he has discovered, is that “there isn’t a better artist than myself”.

Georg Baselitz: A Life in Print is at the Kode art museum in Bergen, Norway, Oct 3-Feb 22. An accompanying book will be published by Skira to coincide with the exhibition