Malaysia has seen a surge in book bans this year in what some publishers, academics and rights groups are calling a dangerous slide toward repression and conservative Islamic dogma.

The Ministry of Home Affairs has banned 24 books this year as of October, more than all the books it banned in the past six years combined and the most in any single year since 2017.

This year’s banned titles include thrillers and romance novels, a collection of poems titled “Masturbation,” non-fiction books about Islam, and guides on puberty for pre-teens.

Nearly half the blacklisted books touch on LGBTQ themes, including the internationally acclaimed novel “Call Me by Your Name,” which was adapted into a 2017 Oscar-winning film starring Timothee Chalamet.

Homosexuality is against the law in Malaysia, where all ethnic Malays are Muslim by law and renouncing Islam can be punished with jail terms by religious courts.

When announcing some of the embargoes, the ministry said it was banning the books “to prevent the dissemination of elements, ideologies or movements that may jeopardize national security and public order.”

PEN Malaysia, the local chapter of the international freedom of expression advocacy group, called the spike in book bans a “shocking” curb on Malaysians’ right to speak and write honestly about important issues, especially those dealing with race, religion and sexuality.

“That can only show how regressive we are becoming and how the democratic space is actually shrinking,” PEN Malaysia president Mahi Ramakrishnan told DW.

“We cannot have dialogue. We are told what to do and books are taken off the shelves, and all we can do is watch or protest. And if we protest, we can also get into more trouble,” she added.

Malaysia’s ‘reformist’ government tilts conservative

The uptick in book bans falls in the third year of the government of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim.

The veteran politician came to power in late 2022 after decades of building a brand around the promise of a more democratic, transparent and just government for all Malaysians, not only the country’s majority ethnic Malay Muslims.

Anwar’s governing coalition operates under a policy framework called “Malaysia Madani” or Civil Malaysia, that includes six “core values” such as respect and compassion.

In practice, however, the administration has proven far more reactionary and pro-Muslim, said Wong Chin-Huat, a political analyst and professor at Malaysia’s Sunway University.

“The increase of banned books might reflect growing conservatism within the state bureaucracy over years — not necessarily starting with Anwar’s ascendance to power — in which perceived deviant or heretical views are not intellectually challenged but just legally suppressed,” he said.

Wong said Anwar’s administration may be amplifying those conservative attitudes, whether out of conviction or for political gain.

“What is certain is Malaysia has not grown more openminded under the Madani government.”

The administration’s appetite for banning books actually looks more like Madani in reverse, said Ahmad Farouk Musa, director of the Islamic Renaissance Front, a local group that promotes a liberal interpretation of Islam.

The group also publishes books, and the Home Ministry banned three of them in 2017. It is currently deciding whether to ban two more, according to Farouk Musa.

“They call themselves Madani, meaning to say they are supposed to be more open, they’re supposed to be more receptive toward different ideas. The thing is that they have gone the opposite way,” he said.

Farouk Musa added the Anwar’s administration crackdown is a calculated ploy for Muslim votes.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim took office promising reformImage: Ajeng Dinar Ulfiana/REUTERS

Islam’s role in Malaysian politics

Although Anwar’s coalition won the 2022 elections, it did so with much help from non-Malay Muslim voters. The Islamist Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) meanwhile, won the most parliamentary seats of any single party in the race, more than doubling the share it won in general elections four years earlier.

In regional elections in 2023, an avowedly pro-Muslim coalition led by the ascendant PAS won 60% of the 245 seats up for grabs, flipping 71 of them and gaining ground in some of the ruling bloc’s strongholds.

Farouk Musa said the sudden spike in book bans is one way for Anwar’s coalition to try and win over more Muslim voters in elections to come, or at least hold on to those it has.

“That’s the main reason, because otherwise they are going to lose out,” he said.

Amir Muhammad, an independent book dealer and publisher, said the books bans are a way to curry favor with voters by “playing the card that they are helping to protect morals.”

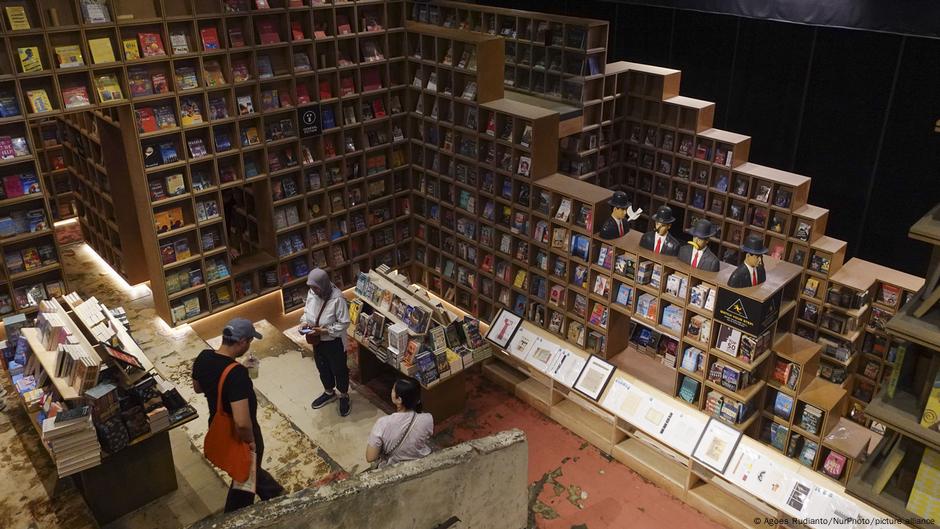

In June, officers from the Ministry of Home Affairs sporting neon yellow vests showed up unannounced at Muhammad’s tiny bookshop in Kuala Lumpur looking for three books.

Muhammad said the titles were two psychological horror novels and a romance, all by local authors, and that the officers left with one copy of each, without explaining why they were under suspicion.

Muhammad said it was at least the fourth time officers from the ministry have raided his shop, and called it an “occupational hazard” of selling books in Malaysia.

“It’s just one of the risks of going into this business,” he said.

The Ministry of Home Affairs did not reply to DW’s requests for comment.

More book bans around the world

By some accounts, book bans are on the rise globally as well.

On World Book Day this past April, PEN International said it had documented a “dramatic increase” in book bans worldwide. But it singled out Malaysia among the dozen-odd countries it highlighted this year for its focus on blocking publications with LGBTQ characters or themes.

According to PEN Malaysia’s Ramakrishnan, Malaysia has been banning more books of late than more liberal neighbors like Indonesia and the Philippines but was still not as strict a censor as Cambodia, Myanmar or Vietnam, countries ruled by authoritarian, communist or military regimes.

“The outcome of all of these [restrictions] converges in narrowing the space for dissenting ideas and … the insidious reenforcing of self-censorship among writers, publishers, distributers and also readers,” Ramakrishnan said.

Edited by: Wesley Rahn