Last month, The Oregonian reported that southern Oregon novelist Sandra Scofield had been nominated for the National Book Award for her second book, “Beyond Deserving.” All that day, bewildered Portland booksellers were calling each other up, asking, “Who the hell is Sandra Scofield?”

– The Washington Post, November 1991

The thrill of discovery faded fast.

Portland booksellers now knew who Sandra Scofield was, but even after news of the National Book Award finalists spread, sales of “Beyond Deserving” remained underwhelming. Few people showed up at her readings.

She quickly slipped back into obscurity.

Thirty-four years later, Scofield remains little-known, despite half a dozen more novels, the most recent arriving last year.

Is there some reason the former Ashland teacher, now 82 and living in Montana, never broke through to a wide audience?

“I did sort of wonder, ‘Why? What’s the difference?’,” she recently said of the period in the 1990s when “Beyond Deserving” and its immediate follow-ups, “Walking Dunes” and “More Than Allies,” scored critical acclaim but tepid sales. “Though it never bothered me deeply. I just shrugged and kept on with my life.”

Scofield always has been dedicated to the pursuit of complete honesty about herself. It’s been the driving impetus of her writing, shown most clearly in her lacerating 2004 memoir, “Occasions of Sin,” which documents her unstable childhood and shattered teenage self-esteem, the sexual assault she survived – barely – in college, and her lifelong struggle to come to terms with her mother’s premature death.

So an hour after she told The Oregonian/OregonLive that she’d shrugged off her stubborn low profile among the reading public, she sent off an email:

“I lied. I grind my teeth wondering why I fell between the cracks. There. But only once in a while!”

***

Portland booksellers back in 1991 may have wondered who Sandra Scofield was, but they weren’t the first. Scofield herself had wondered for years.

She thought the answer could be found by figuring out the secrets of her late mother’s life.

Young Sandra Scofield in Mykonos, Greece. (Courtesy of Sandra Scofield)Courtesy of Sandra Scofield

Young Sandra Scofield in Mykonos, Greece. (Courtesy of Sandra Scofield)Courtesy of Sandra Scofield

She could vividly recall what was supposed to be a turning point for Edith Hambleton. Scofield was a little girl sitting in a rundown car, her mom about to climb in.

“It’s my life, Mother!” Edith yells at the figure standing in the doorway of the house. Edith steps into the car and slams the door, the sound so loud and shocking there’s no doubt it means the end of something, maybe of everything.

Up until then, young Sandra Jean’s life had been tension-filled but predictable, living in her grandmother’s small house on a dirt street in Wichita Falls. Edith, a high-school dropout who became pregnant at 16, worked as a carhop at a drive-in restaurant called The Pig Stand. Her grandmother packed flour at a General Mills plant.

Edith was an odd duck in the small, conservative West Texas city, reading literary novels, raging at Sen. Joe McCarthy’s communist-hunting hearings on the TV. She doubled-down on her outsider status by converting to Catholicism.

As a first-grader, she later insisted, Scofield understood how her coming into existence had upended her mother’s life, that Edith “had lost something important because of me, a chance to choose a better path, and I vowed right then to make it worth her while to be my mother.”

It was a promise she couldn’t keep.

Her mother tried to strike out on her own and create a life for herself, but before long she fell ill. Edith had a hysterectomy, then contracted hepatis in the hospital. A debilitating depression followed. Soon – increasingly dependent on drugs, her body betraying her – Edith found herself in a mental ward.

Scofield has worked through these and other memories, in one way or another, in all of her books.

Her memoir opens on an unexpected scene: Edith, hollow-eyed, posing nude in her bedroom for a photographer, a neighbor, just weeks before she died at age 33.

The cover of Sandra Scofield’s novel “Plain Seeing” features a photograph of her mother.Handout

The cover of Sandra Scofield’s novel “Plain Seeing” features a photograph of her mother.Handout

Scofield found the photo proofs not long after Edith’s death. She would surreptitiously return to them over and over, trying to get a bead on the mother who left her far too soon.

“How many times I have studied those pictures, trying to guess what she was thinking,” Scofield writes. “Did she like showing her body to the camera? To the man [taking the pictures]? To those of us who would see it later? Was she remembering her youth, or did she think she still had that special something? She does not look like a woman anticipating death.”

When her mother died, the teenaged Sandra Jean began to spiral, convinced she wasn’t a good person, that she too was doomed. The nuns at her Catholic school told her that, to have any hope of being saved, she had to abandon pride and “blow away your fancies.”

“And I did,” Scofield would recall, “for years and years, until long after I stopped praying for anything else at all.”

***

Scofield turned to books as an escape.

At last she had found something that could take her out of her grief and fear – and ultimately out of her constricting circumstances.

She landed at Odessa Junior College, and she rode her academic momentum to the University of Texas. But her progress was derailed after she got drunk for the first time while hanging out with a group of frat boys. She passed out – and then suddenly “woke to the sensation of suffocation,” she wrote years later. She was naked, and one of the boys was on top of her. The others would follow suit.

Scofield blamed herself. She never told police or college officials.

She left school and traveled, through Europe and Mexico, trying to forget what had happened. But eventually she returned home, earned a bachelor’s degree and then attended graduate school in Illinois and New York.

She ended up in Eugene with a husband, Allen Scofield, and a young daughter, Jessica. She completed a Ph.D. at the University of Oregon, pulled the plug on her youthful marriage and began a career in educational research.

Through her work she met Bill Ferguson, then a teacher and education administrator in Montana, and fell hard. He did the same.

In 1975 she and Ferguson married, and the couple and Jessica moved to Ashland. Finally, Sandra Scofield was happy, comfortable in her own skin.

But her past, her long-gone mother, still haunted her.

At 40, even though she hadn’t published a book and didn’t have a literary agent, she decided to concentrate on her writing, giving up the grade-school and high-school teaching she’d been doing.

“Bill was solid as a rock, so I could flit a bit,” she said.

But she didn’t flit. She worked hard. She published short stories and poetry, winning a Katherine Anne Porter Prize, and hashed over her personal history in endless drafts.

She began to view herself as a character, thinking that she “lived in a story.”

She wrote in the middle of the night while her husband and daughter slept, and after five years she had a manuscript.

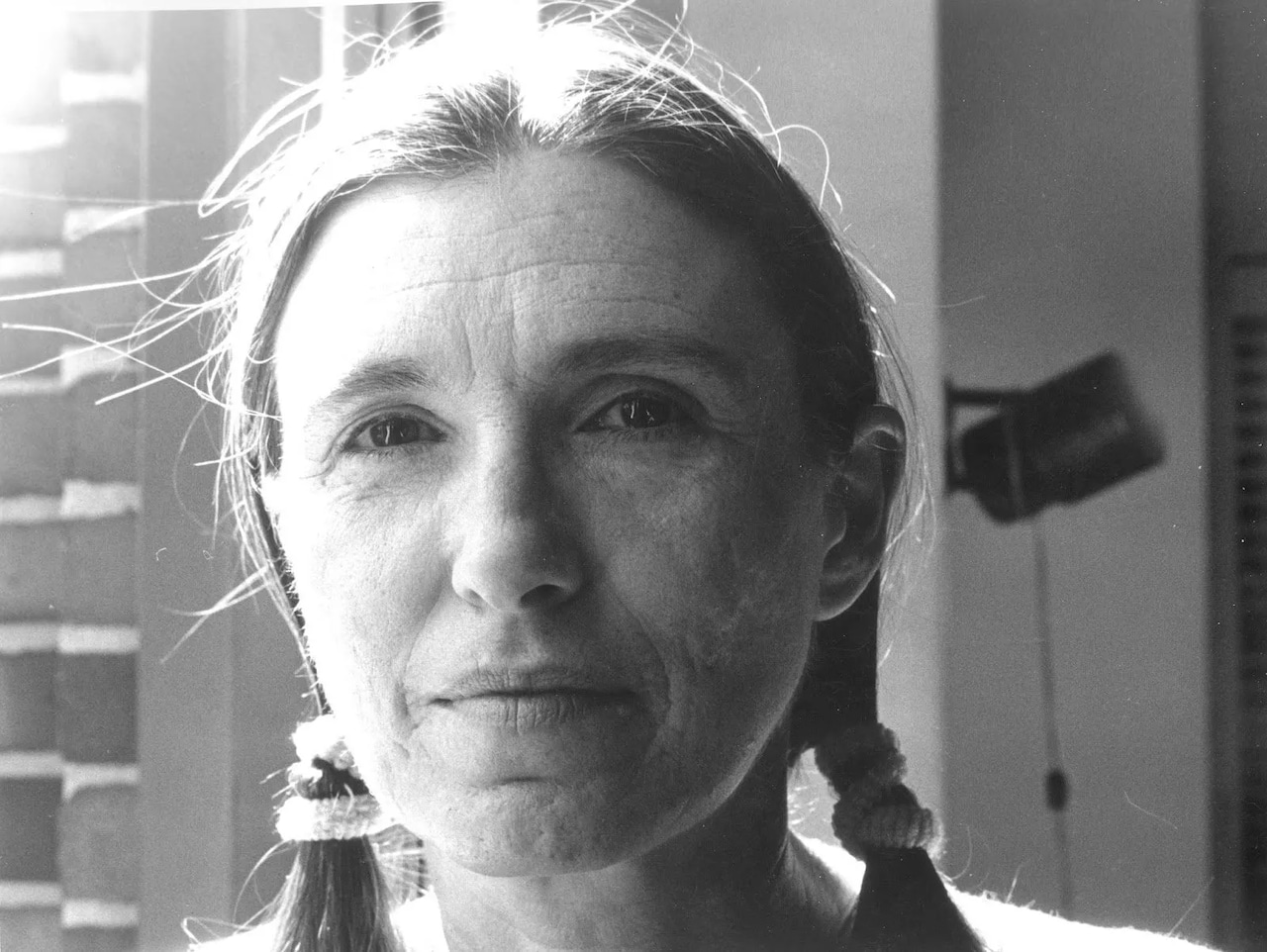

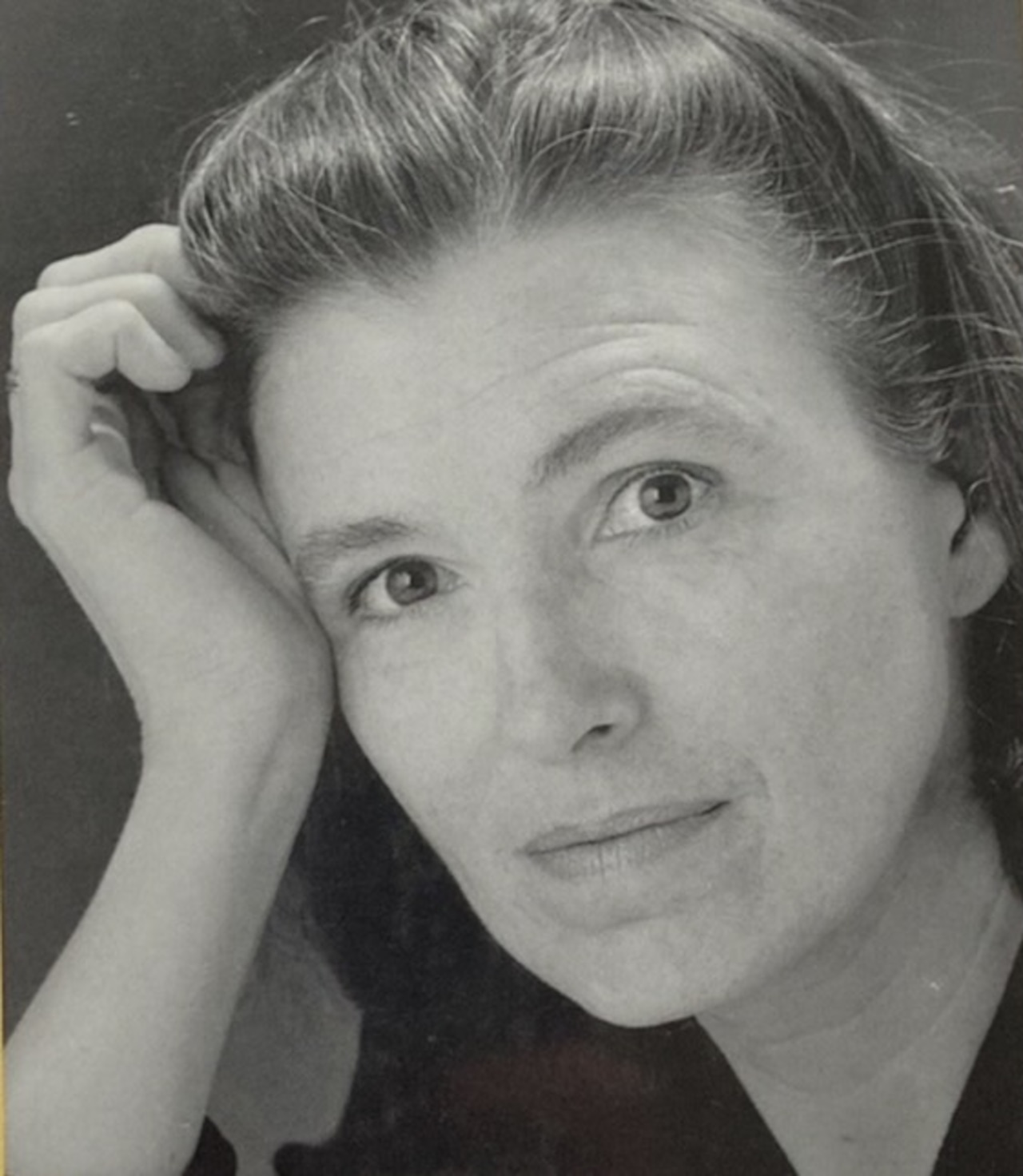

The author photo, by Christopher Briscoe, on the back cover of Sandra Scofield’s first novel, “Gringa.”Christopher Briscoe, from back cover of book

The author photo, by Christopher Briscoe, on the back cover of Sandra Scofield’s first novel, “Gringa.”Christopher Briscoe, from back cover of book

That first novel – “Gringa,” about a traumatized American woman trying to find herself in Mexico – hit bookstore shelves in 1989. Scofield gave tandem readings in Portland with another unknown Oregon author, Katherine Dunn, who was hawking her new novel, “Geek Love.”

“Geek Love” took off. “Gringa” didn’t.

Then, two years later, came “Beyond Deserving,” a family drama set in a fictional version of Ashland and dedicated to Bill and Jessica, as well as to her ex-husband, Allen, who had died in a car crash. The accolades rolled in.

The New York Times called it “an intelligent and observant novel.” The National Book Foundation, in naming its award finalists, described the book as “often funny, sometimes sad, always wise.”

But “Beyond Deserving,” like “Gringa,” remained an aficionado’s taste only, selling just 6,000 copies in early printings. And it didn’t win the National Book Award. (The prize went to Norman Rush’s “Mating.”)

It didn’t matter, Scofield told herself. Writing had saved her.

She had many regrets, an endless array of regrets from her youth and beyond, but now she didn’t stew over them like she used to. Writing released them, so she could “celebrate the good luck I’ve had in life – and focus on living another day.”

She poured out novels, short stories and essays throughout the 1990s and into the new century, while also leading creative-writing workshops. Her latest novel, 2024’s “Little Ships” – also set in Ashland, where she and Ferguson lived for nearly 30 years – was published by a small press in Denver.

Kirkus Reviews has called her work “potent – it could bring tears to your eyes.”

The New York Times wrote that she “is one of those writers who are as good at not saying things as they are at saying them.”

But that didn’t mean her books were easy to read. They required emotional fortitude. Her characters – real as well as imagined – were always working out entrenched trauma of one sort of another.

In a magazine essay, Scofield wrote about how she began screaming when she went into labor with her daughter – and unexpectedly found succor in the vocal release. “Once I started – it was easier than I anticipated – I could not stop.”

In her 1998 novel “Plain Seeing,” about a self-destructive woman and her mother who died young (and which features a photograph of Edith on the cover), her fictional alter ego “thought there was only pain, that it lasts forever, that she couldn’t give in, or show it to anyone.”

Though bestselling success continued to elude her, Scofield never considered taking the route paved by other literary novelists (such as Kate Atkinson, one of Scofield’s favorite writers) of penning genre novels on the side to broaden her audience.

“Commercial writers, who turn out one book after another, they have a special gift,” she said, citing Stephen King as the foremost example out there. “They have a gift for story, and it’s not personal. And then there are people like me, who walk around with a personal story inside that has to come out. That’s an entirely different thing.

“I only have my story,” she said.

Her current project, which she expects to be the last book she ever writes, is another autobiographical novel, called “All the Nuns Are Dead.” It’s inspired by her adolescent years at Catholic boarding schools in Texas.

But even if “Nuns” is the last book she writes, it might not be her last opportunity to pull her way back up through the cracks and into readers’ view.

Talking about her life and career with The Oregonian/OregonLive prompted her to dig out some old, dusty boxes she had stored in the house, she said. She found lots of “story starts” in them, ideas for novels, notes she hadn’t looked at for years. Her life, in her own hand.

She also discovered finished stories that she’d never published and had forgotten about – and, reading through them, realized they were pretty good.

“I’ve been wondering what to do with them,” she said. “I might type some of these out.”

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.