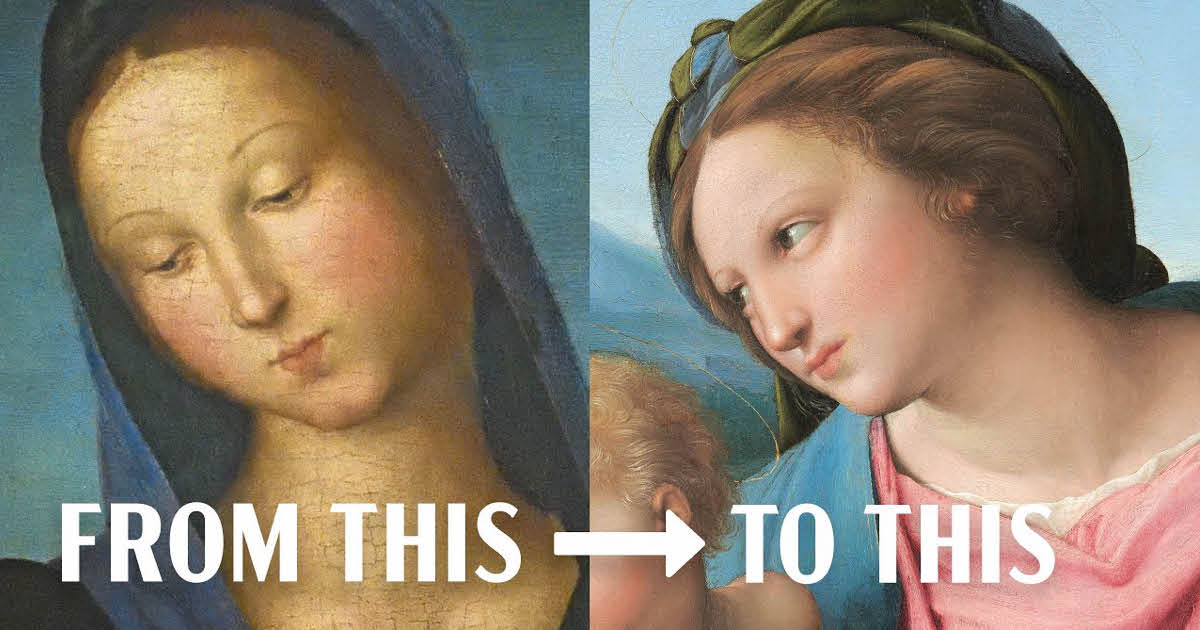

Even the world’s most talented old masters advanced their craft, skill, and vision across time. For Evan Puschak, that evolution can best be traced by comparing artworks that feature the same subject at different points in an artist’s career. A new video essay by Puschak, published through his Nerdwriter YouTube channel, explores exactly that through the lens of Raphael’s numerous Madonna paintings.

Raphael is widely considered to be one of the defining artists of the Renaissance period, alongside luminaries like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Like many of his contemporaries, Raphael often preferred biblical, religious, historical, and other mythological themes, as seen in such masterpieces as The School of Athens from 1509–1511 and the Deposition of Christ from 1507. That preference is also reflected in his various “Virgin and Child” compositions, the first of which he painted in 1502 at only 19 years old.

“You can see that Raphael has a sense of three-dimensional bodies and how to make them feel like they’re part of the space that they’re in,” Puschak explains in the video. “[But] there’s an awkwardness in the arrangement of the figures, especially St. Jerome and Francis, who are cramped in at the sides and pushed forward so that there’s no separation from the Virgin and Child in front of them.”

As Puschak continues, Raphael lacks a strong command over narrative, emotion, and relationship in this early painting, which merely echoes the thousands of other Madonna paintings circulating during this time. After all, these were a hallmark of devotional art both before, during, and after the Renaissance, seeing the Madonna “enthroned and, following the Byzantine style, backgrounded by a flat plane of gold with golden halos.”

By 1505, Raphael returned to the subject yet again, this time improving dramatically. With Madonna of the Meadow, he opted for a pyramidal structure, a method derived from da Vinci. He also introduced the sfumato technique, where transitions between colors and tones are softened to produce a seamless gradient. The result is a more immersive scene, where Raphael’s three figures seem to truly exist within their surroundings.

“The composition is sophisticated,” Puschak says. “There’s a narrative here. In the Florentine Madonnas of this period, Raphael is learning fast.”

Later, Puschak considers what he believes to be Raphael’s greatest Madonna: Alba Madonna from 1511. The circular canvas inherently adds a dynamism to the painting, only enhancing the movement of the three figures, grounding the composition. The details are tactile and rich, while the poses are expressive and incredibly three-dimensional. Above all, though, Raphael has finally achieved a distinct narrative.

“Everything Raphael has learned comes together in this image,” Puschak argues. “The arrangements of Leonardo, the physicality of Michelangelo, the serenity of Perugino, the geometry of Pierro, the clarity of the Netherlandish landscape—it’s all here, filtered through and augmented by Raphael’s genius.”

Impressively, there’s less than a decade between Raphael’s Alba Madonna and his first Madonna painting. To contrast both scenes is to illustrate the drastic improvements within his practice, all while showcasing what made him an old master to begin with.

Head over to Puschak’s YouTube channel to enjoy the full video and analysis.

A new video essay by Evan Puschak at Nerdwriter traces the artistic evolution of Raphael through his numerous Madonna paintings.

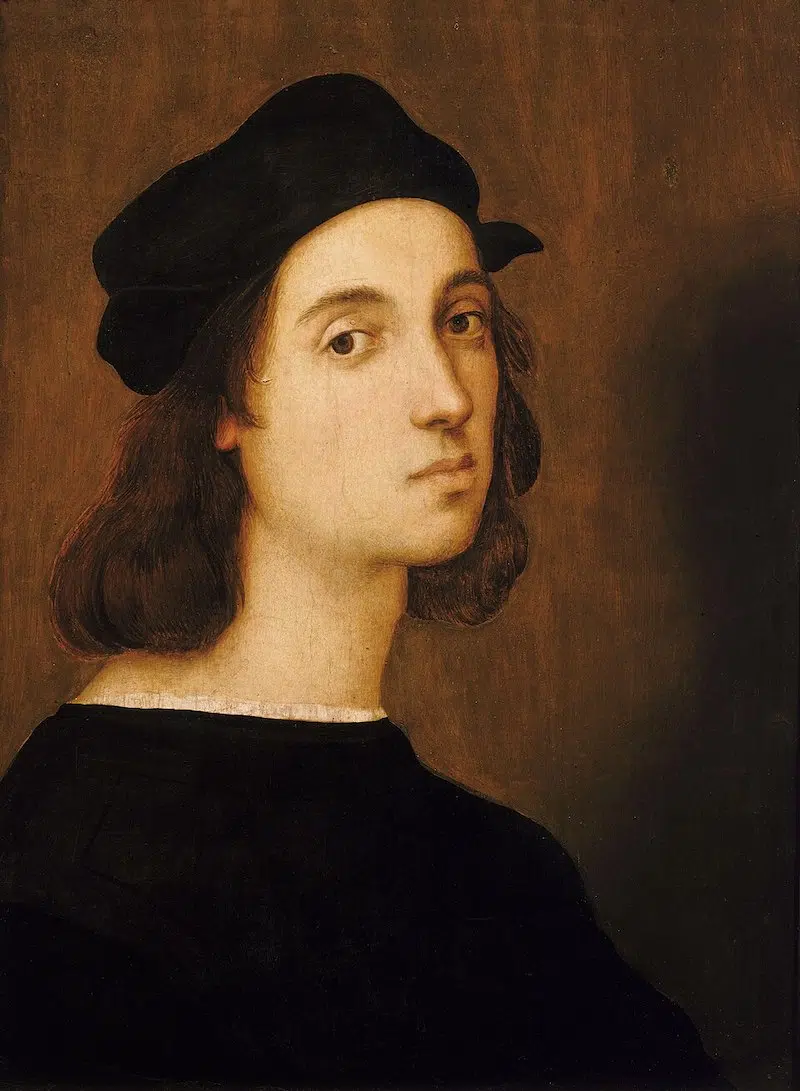

Self-portrait of Raphael, aged approximately 23, from between 1504-1506. (Photo: Nevsepic, Public domain)

The video begins with Raphael’s first Madonna composition, painted in 1502, and concludes with Alba Madonna, created in 1511.

“Madonna, Child, and Saints,” 1502. (Photo: Gemäldegalerie Berlin via Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0)

“Alba Madonna,” 1511. (Photo: Andrew W. Mellon Collection, Public domain)

Throughout, Puschak offers an exciting and comprehensive glimpse into how Raphael went from young genius to Renaissance master.

“Madonna in the Meadow,” 1505-06. (Photo: Google Arts & Culture, Public domain)

Nerdwriter: YouTube

Sources: How Raphael Became A Master

Related Articles:

Watch Two Art Historians Demystify Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’

Why Michelangelo’s ‘David’ Is an Icon of the Italian Renaissance

You Can Take a Walk Through the Sistine Chapel With This 3D Virtual Tour