He grew up in rural Surry County as the youngest of 12 children to a father who paid the bills with a 34-year career processing hog meat at the Smithfield plant.

Unlike his father, Antonio Charity chose a career that many considered unpragmatic: He became an actor.

As a young man, he left Virginia in search of big city stages. And like his father, he never gave up.

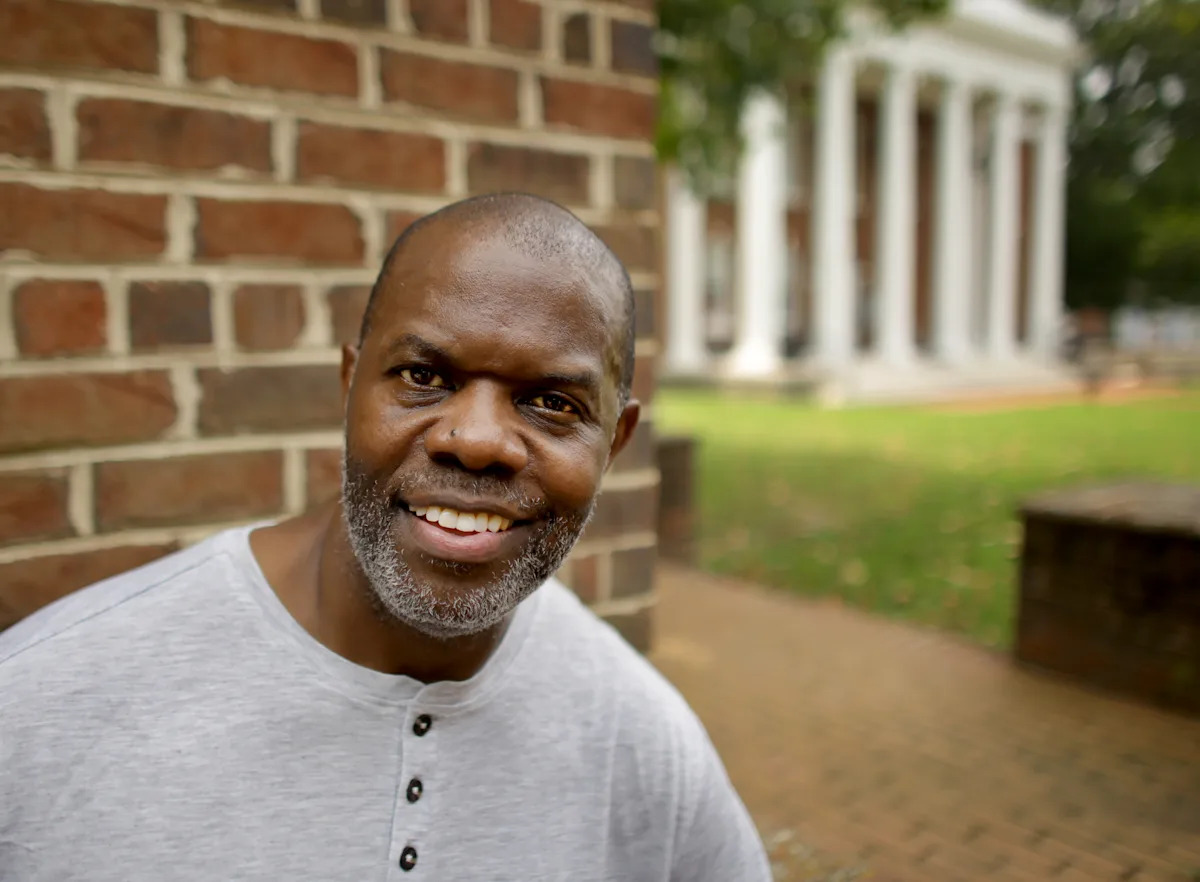

Thirty years later, Charity, 53, left Los Angeles in March and returned home with over 100 combined film and TV credits. Surry County is now the place he’s teaching a new generation of actors — and the setting for his forthcoming documentary.

Charity used his extensive industry experience and Hollywood connections to make “Where Charity Began” to explore his family’s 400-year history in Virginia.

He can’t remember a time when he didn’t want to be an actor. Forever called to the limelight, he’d stand on kitchen countertops as a toddler singing along to the radio. Older siblings still laugh about his renditions of Kool & The Gang’s “Hollywood Swing.” After graduating from Surry High School in 1990, he enrolled at Howard University as a theater major.

Senior year, he landed his first TV role, playing Kid Funkadelic on the NBC series “Homicide: Life on the Street” in an episode that guest-starred Robin Williams. For several years, he’d cling to that memory when times felt tough and parts were few. He’d worked alongside a star, he’d remind himself. He could do it again.

After college, he moved home and got a job at the meatpacking plant.

“My daddy did it for 34 years. I figured I could do it for one year. I couldn’t,” he said.

He moved to New York City at 23 and performed in off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway stage shows for the next nine years while booking TV parts, including roles on episodes of “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit,” a made-for-television film called “Something the Lord Made” starring Alan Rickman and rapper Mos Def, and the 2005 feature film “The Salon” starring Vivica A. Fox.

It was his recurring role as a corrections officer on the HBO series “The Wire” that boosted his confidence to move to Los Angeles. He’s not a celebrity, but with his dozens of appearances on TV and in indie and feature films, Charity has long maintained his status as a professional working actor. He never seriously considered making his own film until three years ago.

He was living in LA with his wife, Tige, and their daughter, Ebony Jewel, who was 10 the night she first heard the Charity family story that has been passed down from one generation to the next.

“Rumor has it that we were never enslaved,” the father told his daughter.

Despite the Black family’s having lived in the South and in Surry County for hundreds of years, he explained to his daughter, no one in their family with the surname Charity was ever a slave.

The dad recalled that his little girl, who listened to his words with wide eyes and peak attention, sat for several moments in silence before replying: “Why isn’t this known?”

“That’s what she asked me,” he said. “As in, she wanted to know why it was a lot of people were unaware of it. Why isn’t it widely known that we Charitys were never slaves?”

She had a point, he thought. People should know.

Prompted to make the documentary, Charity started digging into documents and researching his family’s American history that dates back to 1619. The Charitys, he discovered, are direct descendants of at least two of the first enslaved Africans in the English colony of Virginia. Their descendants were forced to toil on Tidewater plantations.

One of those descendants, a woman with the first name Charity, was enslaved on a Surry County plantation owned by Arthur H. Jordan at the time of his death in 1698. And Jordan freed her in his will: “I do also will and warmly desire that my Negroe woman Charity be and immediately after my decease quietly posses and enjoy her freedom …”

A generation later, her descendants took her first name as the family’s surname, and so, since 1698, no one in the Charity family of Tidewater was ever again a slave.

The documentary is in post-production and is expected to be released next year.

Colin Warren-Hicks, 919-818-8139, colin.warrenhicks@virginiamedia.com