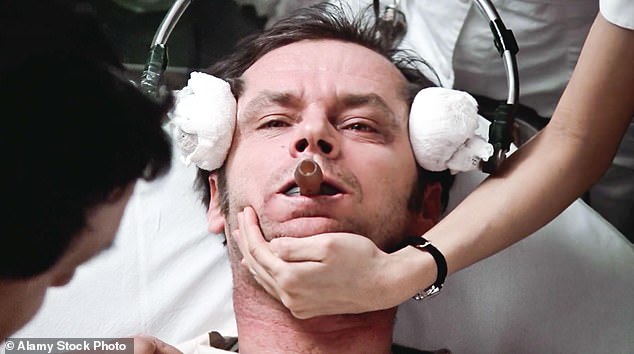

For many of us who don’t know better, the very mention of electric shock (or electroconvulsive) therapy (ECT) conjures up dark thoughts of locked wards, nightmares and Boris Karloff movies of the 1950s. And, of course, of Jack Nicholson being forcibly strapped to a gurney after feigning mental illness in the 1975 movie, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest.

We know the basics. Or at least, we think we do.

That it is a barbaric, basic and highly controversial procedure that has been used by some psychiatrists on their critically ill patients since the 1930s.

That before the current is switched on, their limbs must be secured to stop them thrashing about. A protector placed in the mouth to stop the tongue being bitten off. Electrodes are applied to the temples and electricity flows into the brain until the patient goes into seizure and everything starts twitching. All in the hope that – a bit like a car with a flat battery – the current jumpstarts the brain out of madness, and back into sanity.

So it goes without saying that most of us assumed ECT was very much a past procedure, safe in the annals of medical history, along with lobotomies and bloodletting with leeches.

But no.

In fact, every year, more than 11,000 patients are given ECT in 99 facilities around the UK. Last month, it was claimed that 1,081 doses of ECT were given to patients in Scotland against their will.

Recently, the World Health Organisation and United Nations warned that involuntary or forced ECT risked breaching patients’ human rights – and could be regarded as a form of torture.

And Dr John Read, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of East London and author of several studies into the effects of ECT, calls it ‘unethical’ and ‘unscientific’, claims there is no evidence that it works and called for its use to be suspended immediately.

‘ECT was developed decades before we had proper ethical standards,’ he says. ‘If it was introduced today as a new treatment, there’s no way it would be approved.’

For many of us, the mention of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) conjures up images of Jack Nicholson being forcibly strapped to a gurney in 1975 film One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest

Recently, the World Health Organisation and United Nations warned that involuntary or forced ECT could be regarded as a form of torture. Pictured: One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest

On the back of this, several former ECT patients – Andy Luff and Dr Sue Cunliffe – have popped up in the press, claiming ECT had had a catastrophic effect on their health.

Cunliffe says that after 21 sessions in 2005, she went from a high-functioning paediatrician and mother of three, to someone who couldn’t read, write, speak without slurring or work again.

‘My brain was frazzled. There was no coming back from it,’ she says.

Andy Luff, who had treatment in 2015, had to relearn how to brush his teeth, make a bed, run a bath and wash his hands. At one stage he was unable to recognise his own parents.

All of which sounds monstrous and extremely scary. And perhaps not surprising that there is a growing clamour for the treatment to be outlawed.

‘Why would anyone in their right mind run an electric current through someone’s brain without knowing if it actually worked,’ says Richard Bentall, professor of clinical psychology at Sheffield University, who is campaigning for more testing of its efficacy.

Which seems a valid question, so this week, I did a bit of digging into the world of ECT – and unearthed a few surprises.

For starters, that no one is thrashing about any more – patients are fully anaesthetised, carefully monitored, treated in hospital theatre conditions and any twitching goes on solely in the brain as milli-second pulses are applied at a frequency of 20 and 120 hertz, causing a seizure.

And that it is the seizure, rather than the current, that jolts the brain and, by encouraging neural connections, can cause a temporary improvement in critically ill patients – often catatonic, or deep in psychosis.

Professor George Kirov, clinical professor at Cardiff University, who has treated 455 patients with ECT, and has written several books on the subject insists that, while it does have adverse side effects, it is a safe and effective treatment and has transformed the lives of so many of his patients.

‘People say it is barbaric and simple, but it works.’

Sue Cunliffe says that after 21 sessions in 2005, she went from a high-functioning paediatrician and mother of three to someone who couldn’t read, write, speak without slurring

I also learned – rather alarmingly – that women in their 60s (who are more prone to depression than men) are most likely to be given the treatment, but apparently respond slightly better to it than men.

But, perhaps most importantly, that ECT is highly likely to erase sections of a patient’s memory – in both the short and long term. (Dr John Read’s research puts this at between 70 and 80 per cent of patients, but practitioners insist it is much lower.)

The loss can be anything from the weeks surrounding the treatment, to holidays, to major life events. By Dr Cunliffe’s account, she lost her entire medical training and the birthdays of her children.

Professor Kirov is quick to admit that many of his patients have suffered memory loss (though he points out that their depression or underlying condition can also be a factor). Some lost a few weeks here and there. One patient forgot he’d given a speech at his wife’s funeral a few years earlier. Another, that she’d had an operation.

But some insist this is small price to pay. Because they say that this extraordinarily basic treatment saved their lives. They also insist they’d have it again in a shot if their mental health spiralled.

Professor Robert Howard of King’s College London, has treated several hundred patients – often psychotic or catatonic – with ECT.

‘I use it bring them back from the brink so that I can treat them with other methods,’ he says. ‘And I can think of very few who haven’t shown some sort of improvement afterwards. Sometimes they become animated within a few hours.’

One of his former patients even has ‘If depressed give me ECT’ tattooed onto his chest, in case he’s ever too ill again to make his wishes clear.

Because for many patients, the alternative is bad enough to embrace the risk.

Today, Jan, 57, a senior NHS manager from West Yorkshire is extremely bright and articulate. But in the in the summer of 2016, she became hyper-manic, deeply depressed, delusional, psychotic and obsessed with suicidal thoughts – all thought to be triggered by hormone changes linked to the perimenopause.

‘All I could think about was ending my life,’ she says. ‘Endlessly researching methods online – what might be possible.’

She was admitted to an acute inpatient psychiatric ward in September 2016 and treated with drugs and therapy, but her condition worsened.

Professor Richard Bental says: ‘It’s a scandal. It is unproven after nearly 100 years of use, and I am baffled why that would be’

But Professor George Kirov insists it is a safe and effective treatment: ‘We don’t say the same for a cardiologist who uses a defibrillator to get the heart going again. It’s the same thing’

Over the next few weeks, she made two suicide attempts that saw her admitted to an acute medical ward. She also absconded from the ward and was found hundreds of miles away, wandering on the hard shoulder of the M1, barefoot in cropped jeans and a T shirt, having abandoned a car that she’d smashed into the central reservation.

‘Nothing was working,’ she says. ‘I’d had five months of looping suicidal thoughts, continuous black despair.’

So when doctors suggested ECT, she agreed. Not because she thought it would work, but because she felt it was her last chance.

‘I knew what it involved, and the stigma, but I had nothing to lose. I would have killed myself otherwise anyway,’ she says.

But within a couple of days, she was much more herself. Visiting friends saw a visible difference. She was able to take part in a conversation. She didn’t look so grey and emaciated.

Like many patients, she suffered memory loss, but hers was of the weeks she was in hospital.

‘It’s a complete blank, nothing! But I was in a psychiatric ward, so I don’t feel I’m missing out on anything,’ she says.

In total, she had 12 sessions, twice weekly and by early March was well enough to be discharged home. Two weeks later she started a phased return to her senior management role.

‘I went back to my children, my family. My life. It saved me and it was the only treatment that worked for me. The effect was like a miracle for me. I would be dead without it.’

Professor Howard admits that no one really knows how it works. ‘But we don’t really know how paracetamol works either. Or a general anaesthetic. But no one gets emotional about that,’ he says.

And he can list ‘tens of patients’ who would not have made it without ECT. Most of whom are now back in their lives.

As Professor Kirov puts it, ‘psychiatry is not like surgery. We don’t have quick fixes. But this is the only treatment that works so dramatically, so effectively.’

But while those who have been saved want to shout from the rooftops, there are many who disagree, fiercely.

Partly because it is so basic and brutal.

‘This is not a gentle treatment,’ says Professor Howard. ‘That’s why people have to be anaesthetised and given a muscle relaxant. Because otherwise the muscle spasms are so strong they could produce fractures in the spine.’

Critics claim the voltage used can be a bit hit or miss – calculated not on the size of the patient, but the excitability of their brain – how easy it is to induce a seizure. Whether they’ve had ECT before.

But it is also alarmingly untested.

As Professor Richard Bentall explains, there have been no large scale tests using a placebo – to see whether it does actually do anything.

‘It’s a scandal. It is unproven after nearly 100 years of use, and I am baffled why that would be,’ he says. ‘If you’re going to pass a big electric current through people’s heads then there is a prima facie case for saying it should be done with caution and with some evidence of effectiveness.’

He and Dr Read and many of those clamouring for its phasing out, also insist there is no evidence of long-term success after the end of the treatment window.

But practitioners disagree.

They say they don’t need it to work in the long term. For them, it’s about pulling a desperately ill patient back from the brink. Giving them a chance to treat them with more conventional methods.

Which is also why so many patients do not consent to the treatment. They are not able to. But due to The Mental Health Act of 1983, doctors are able to override patients’ wishes when they do not have capacity.

‘Yes, it feels crude,’ says Professor Kirov. ‘But we don’t say the same for a cardiologist who uses a defibrillator to get the heart going again. It’s the same thing. It’s an electric shock.’

While the debate rages in the UK, it is perhaps worth noting that more than 1.4million people are given ECT globally each year. And that treatment numbers are far higher in Sweden (five times the UK), Norway, Finland, France, Germany and the US than in the UK. All, of course, highly developed countries with sophisticated health care industries.

Here, however, numbers are falling and are likely to continue to do so. Much to the horror of Jan.

‘The thought this would not be available if I became so ill again is very scary. It is the only thing that worked for me.’

Karen, 60, a grandmother from Leicester, also had memory loss after four courses of ECT between 2010 and 2016. In the months after she was discharged she went on a family holiday to Cyprus. ‘I can’t remember any of it. I have the photos and can see myself there. But nothing,’ she says. ‘But thanks to the treatment, I can go on more holidays and make new memories. If I hadn’t had ECT I would have been dead.’

Of course some people have not been so lucky.

Dr Cunliffe has never been able to return to work. Today she tires easily and feels fuzzy, but most of all, she is furious.

That she wasn’t told of the extent of the risks – ‘they knew people were suffering life-changing injuries’. That the doctors kept upping and upping her dose. That she – and she claims many like her – didn’t realise that she was consenting to a catastrophic brain injury.

But also that, after her life imploded, she was given no support or help by the health service.

It is hard to think of a more polarising treatment. Or one that attracts more vitriol on X or other social media.

On one side, people who claim it has snapped them back from the brink and saved them from certain death. And on the other, people like Dr Cunliffe, whose life has been smashed to bits.

It is a nightmarish scenario and hard to know what we would do if, God forbid, one of our family members were as ill as some of these poor patients?

Would we want them knocked out, given a muscle relaxant, wheeled into an operating theatre where a paddle is held to each temple and the volts turned up to shock them into a potentially brain-damaging seizure?

Of course not. But we wouldn’t want them to be left to die, or left wandering around the M1 trying to kill themselves, either.