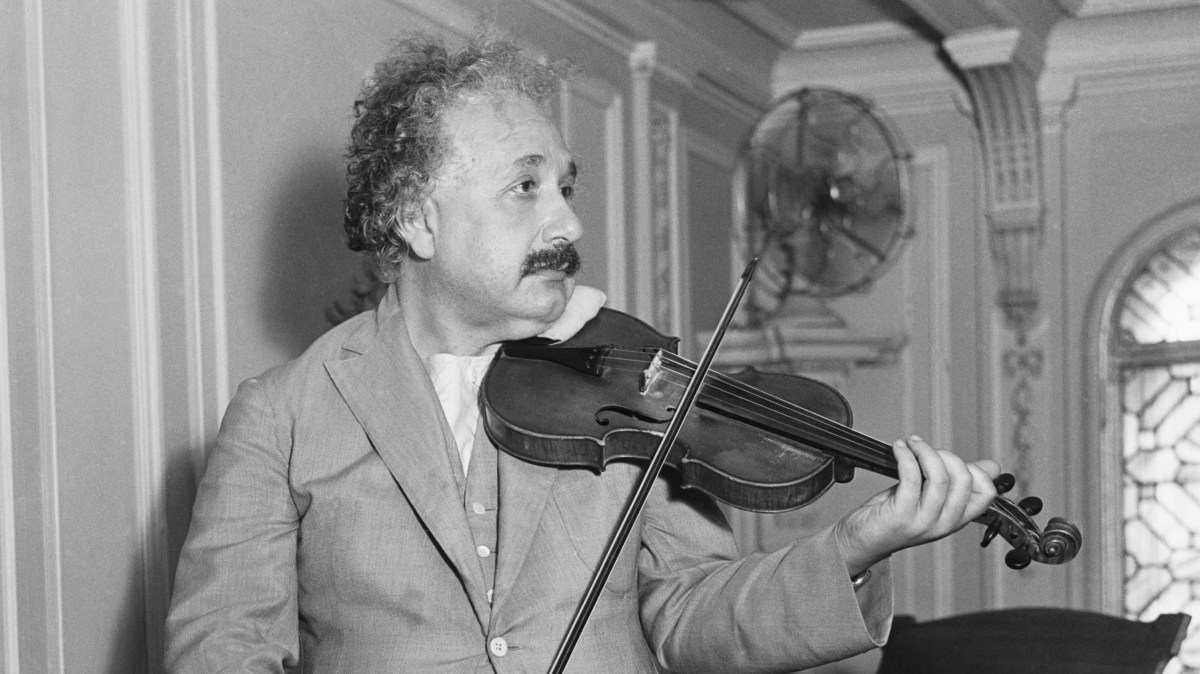

Albert Einstein said that if he had not been a physicist, he would have been a musician. “Most joy in my life has come to me from my violin,” he once confessed.

Now, 70 years after his death, the instrument he played while pondering his groundbreaking theory of relativity has been identified, by a Cambridge University scholar who never meant to go looking for it.

Dr Paul Wingfield, a musicologist and composer, set out to write a musical about Einstein’s life as a violinist and ended up tracing the provenance of a mysterious instrument.

The story began at a wake. In March last year, Wingfield attended the funeral of his brother-in-law, Joseph Schwartz, a lifelong Einstein enthusiast and co-author of Einstein for Beginners, an introduction to his life and thought. On a table lay Schwartz’s book and, beside it, a family photo album showing a young boy with a violin. “The juxtaposition sparked in my mind the idea of a musical drama in which Einstein tells the story of his life, not as a physicist but as a violinist,” Wingfield said.

He began composing Einstein’s Violin, a piece for violin, piano and actor, drawing on Einstein’s writing and recorded comments about music. “By the end of six months,” Wingfield says, “I’d learnt more about Einstein’s musical life than was probably healthy.”

The show premiered last April in Highgate, north London, starring the actor Harry Meacher, the violinist Leora Cohen and Wingfield on piano. After one performance, the theatre manager handed him a note that began, reassuringly, “I am not mad…”

It was from an auctioneer who had been asked to sell a violin purportedly owned by Einstein, who wondered whether Wingfield, having written Einstein’s Violin, would investigate its origins.

Over the following months, Wingfield found himself playing detective: poring over letters, analysing witness accounts, plotting Einstein’s movements across Europe and comparing handwriting samples from his schooldays. He learnt about violin varnish, Belgian customs rules and the exact span of Einstein’s hands.

The clinching detail was the inscription “Lina” on the instrument, the name Einstein gave all his violins.

“I am now as sure as anyone could be,” Wingfield said, “that this violin was indeed once Einstein’s. It cost him — or his parents, actually — 500 marks, which is about £4,000 in today’s money.” The instrument is due to be sold by Dominic Winter Auctioneers in Cirencester on Wednesday. It is expected to fetch between £200,000 and £300,000.

Einstein’s family are thought to have bought the instrument in Munich in 1894, before he left for Switzerland. He played it throughout the period in which he developed his theory of relativity before buying a new violin in Berlin in 1920.

In 1932, just before he fled Nazi Germany for the United States, he gave the Munich violin, along with a bicycle and two books, to his friend and fellow Nobel laureate in physics, Max von Laue. Twenty years later, Von Laue gifted the violin and other items to a friend, Margarete Hommrich, whose great-great-granddaughter now owns them.

Wingfield said: “There are stories … from when Einstein was developing his theory of relativity that whenever he got stuck, he’d practise Bach or Mozart on this violin.

“I think he used it as a way of mulling things over. He didn’t say that he thought there was any strong relationship between music and physics. It just really helped him order his thoughts.”

Philip Brown performs maintenance on the violin at his workshop in Newbury, Berkshire

PHIL CANNINGS/HARTLEY

Wingfield’s day job is director of studies in music at Trinity College, Cambridge. His scholarly interests run to Czech composers such as Janacek and Martinu and the intricacies of 19-century sonata form. By accident, rather than design, he now finds himself an authority on Einstein’s musical instruments.

“I’m not an expert on 19th-century violins,” he said. “But by a quirk of circumstance, my research into Einstein’s musical life made me the obvious person to investigate the story.”

In a twist the great physicist might have enjoyed, the man who wrote Einstein’s Violin ended up identifying the thing itself.