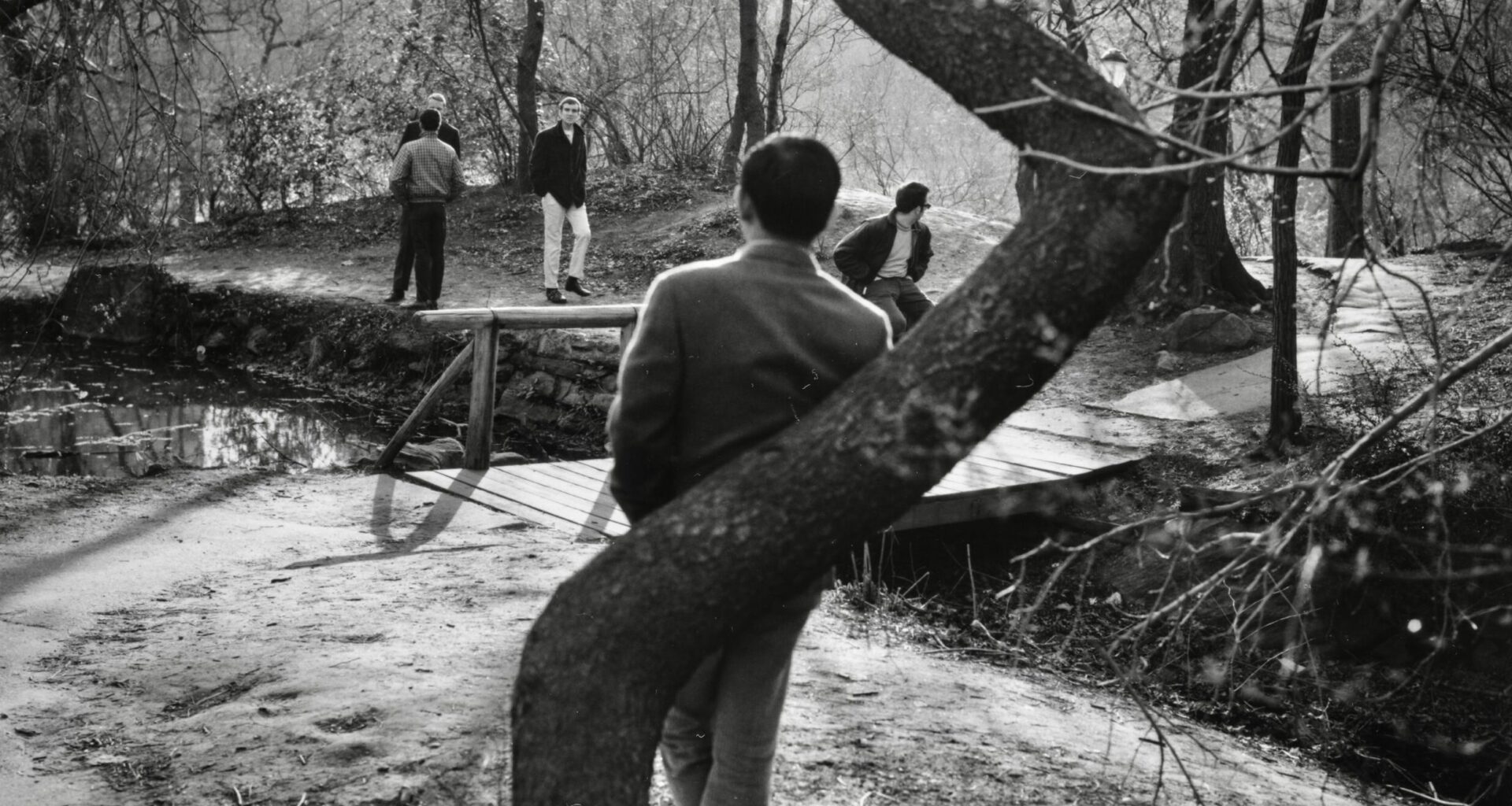

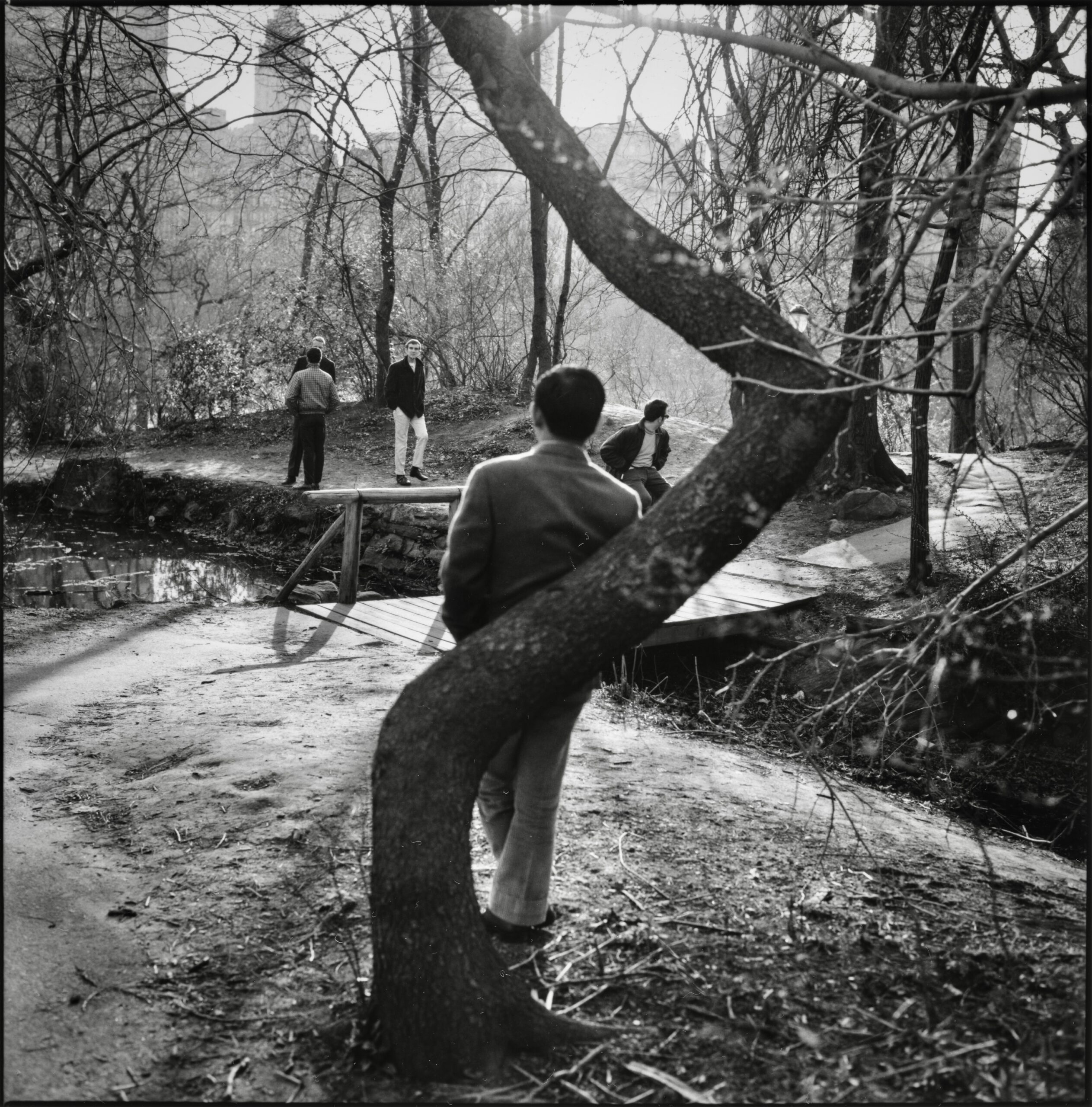

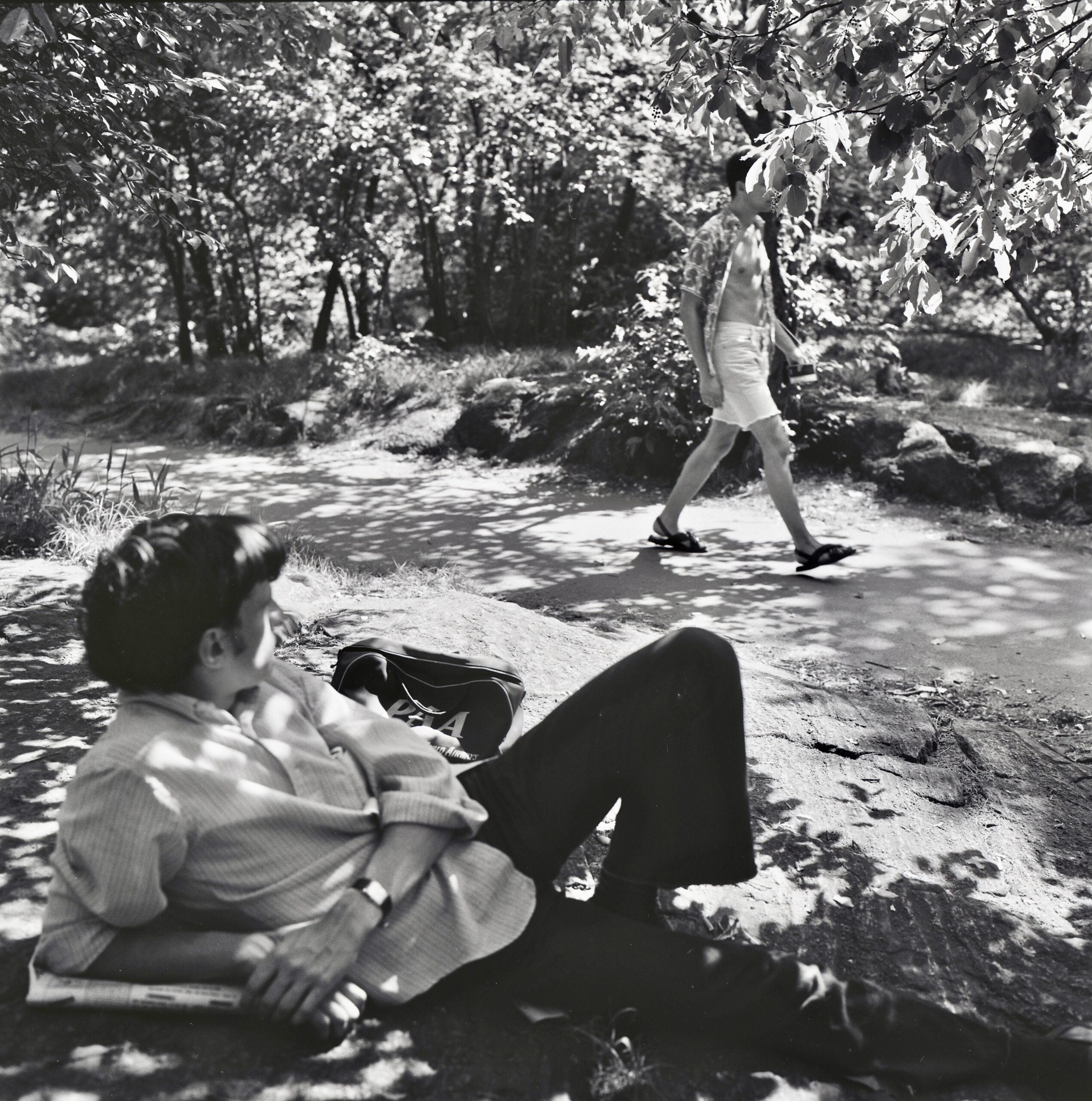

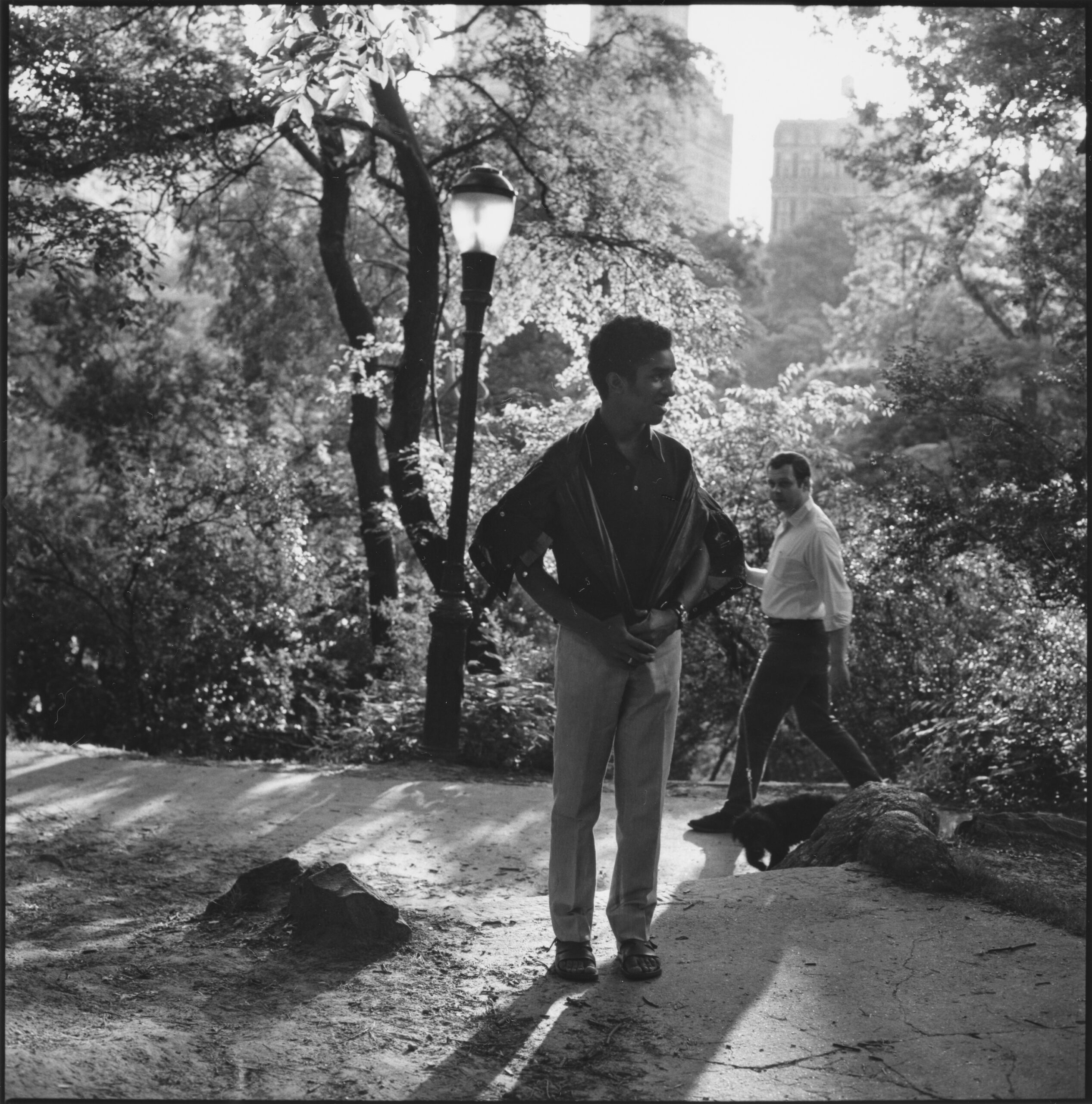

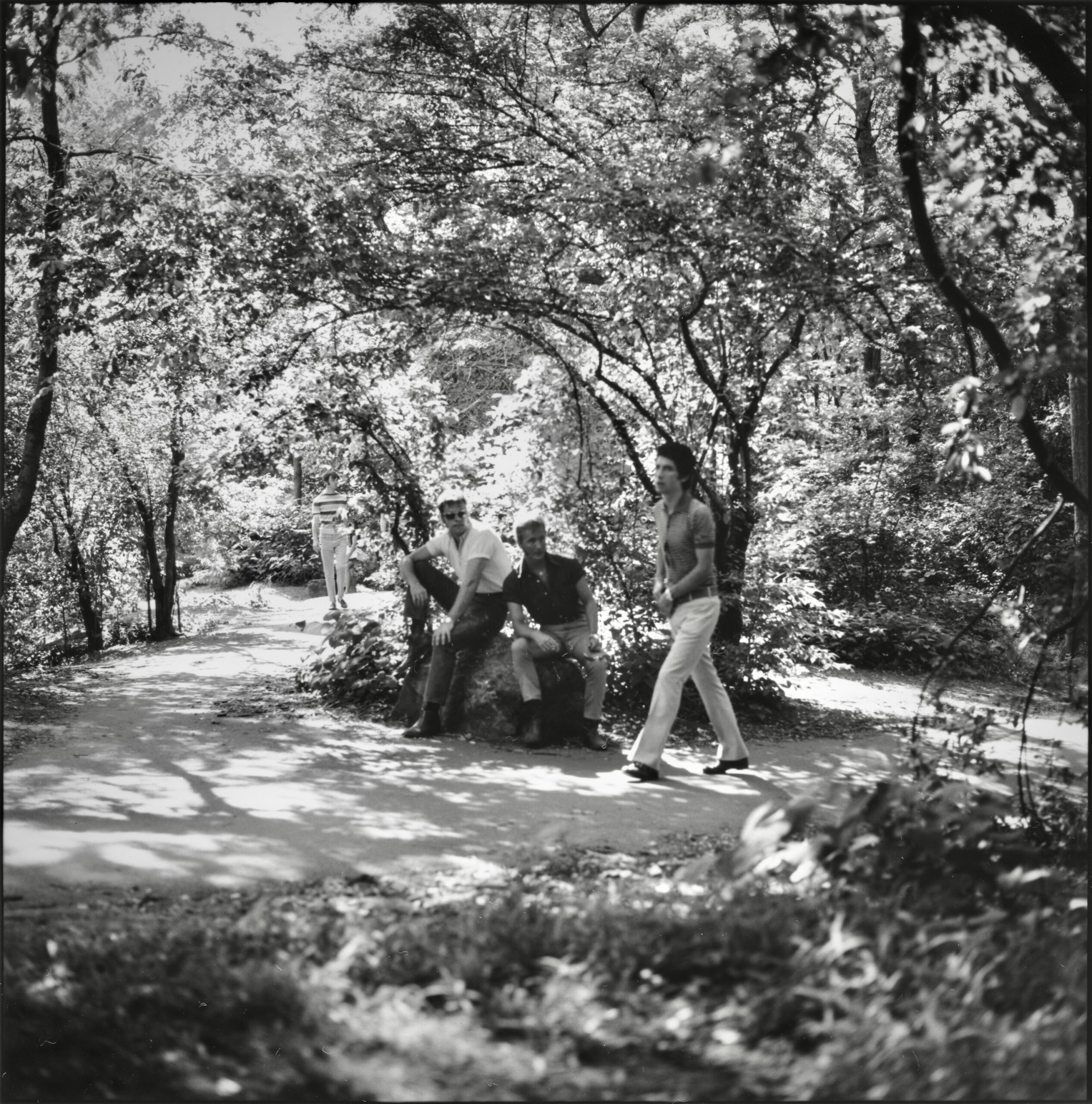

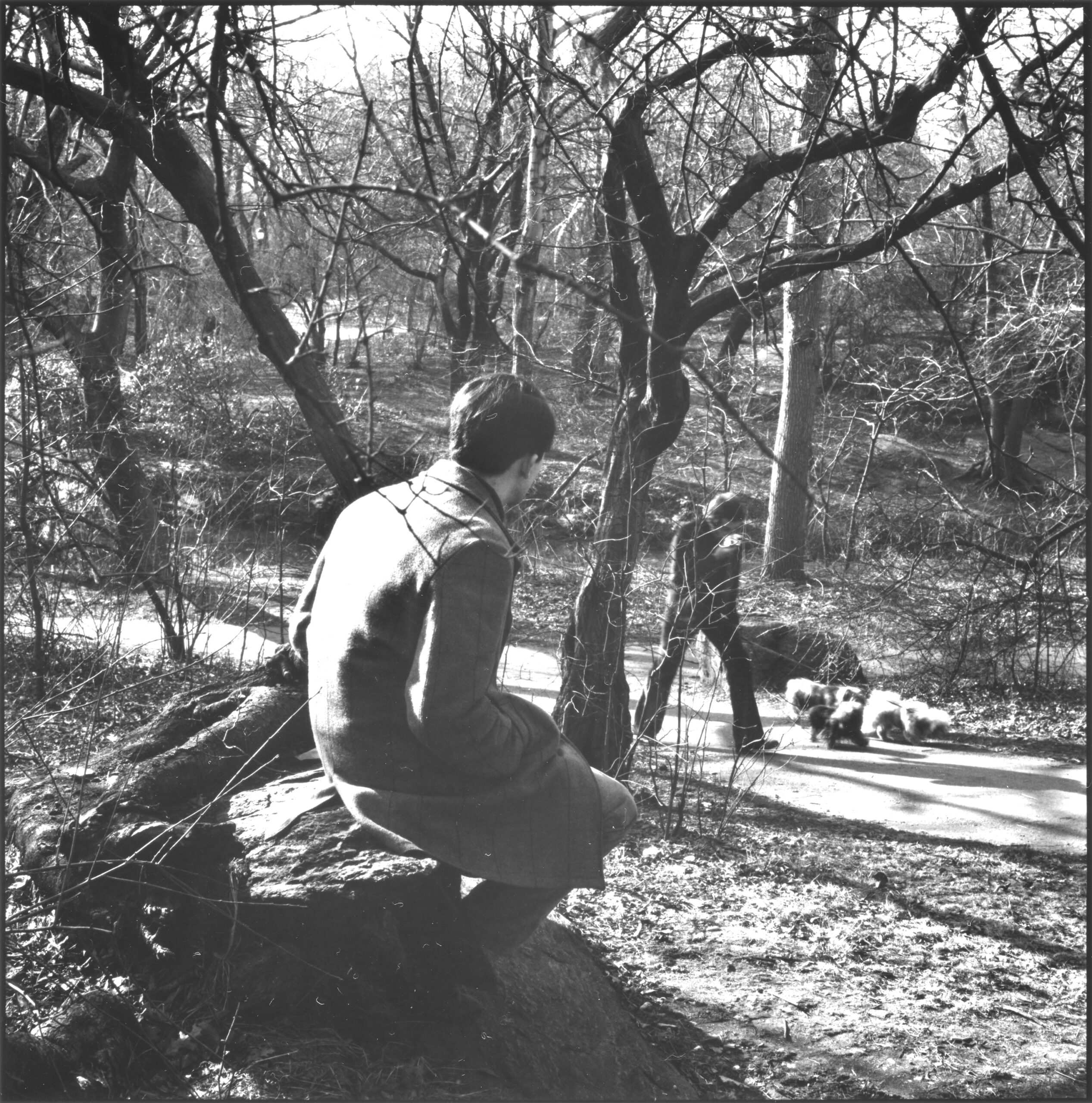

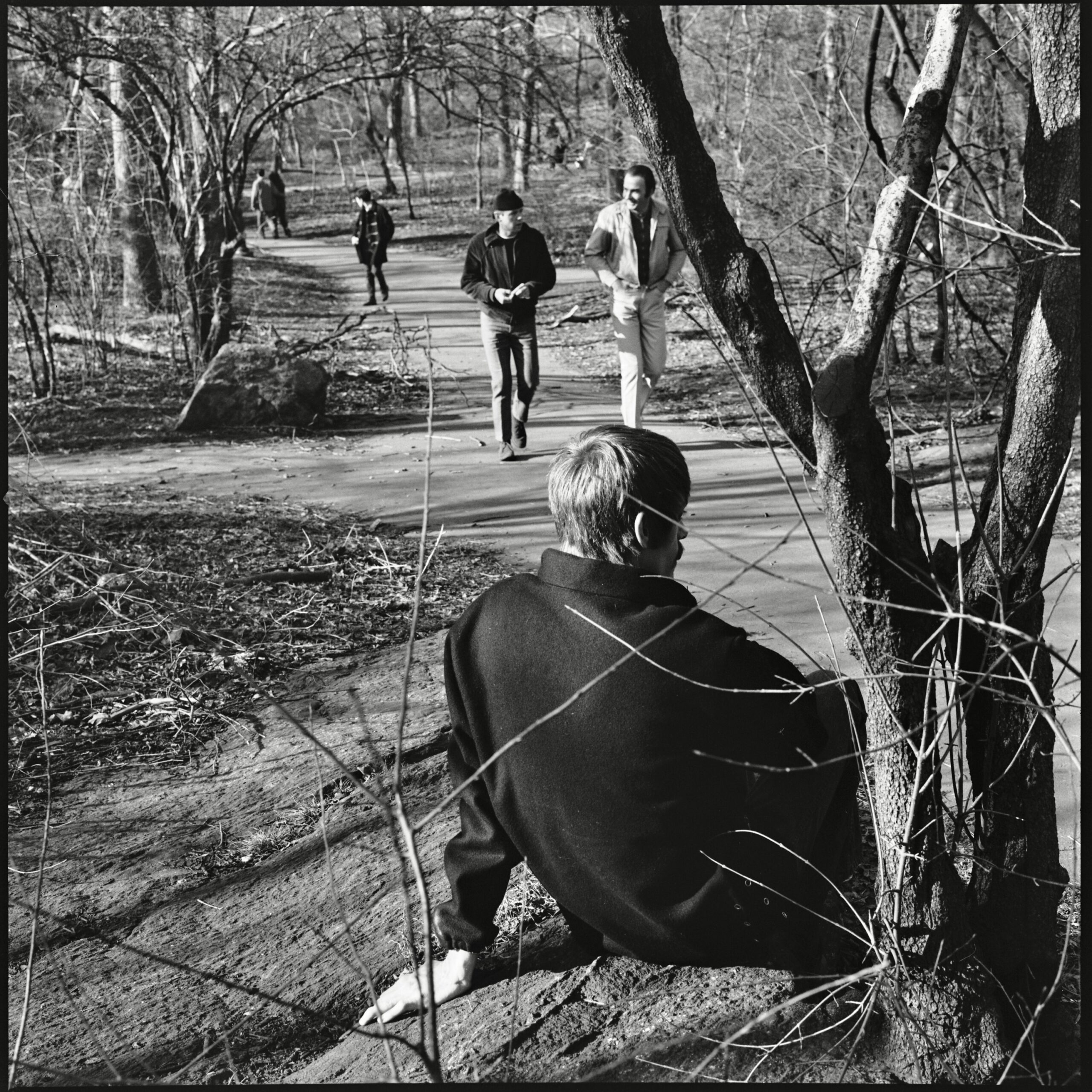

All photos by Arthur Tress.

In the 1960s, when the photographer Arthur Tress began photographing The Ramble, the shadowy and overgrown stretch of Central Park that’s served as a cruising ground for gay men for nearly a century, he hadn’t considered that the images he was capturing might one day find an enthusiastic audience, let alone be considered either art or ethnography. “They were mostly for myself,” he explains, “but I had a sense that they were historically important.” Over 50 years later, Tress’s photographs—noirish, dreamlike scenes in which men lurk and leer, wait and watch—are getting their due. This month marks the publication of The Ramble, NYC 1969, the very first collection of Tress’s Ramble photographs and a vital, provocative document of a time when queer city life happened largely in the shadows. “It was a kind of social commentary on the paranoia, anxiety, loneliness, and frustration of gay men at that period,” the photographer told Prince Faggot playwright Jordan Tannahill last month. “We really don’t like that self-image of the wounded homosexual. But I think what’s going to make these pictures interesting to people is that we’re ready to acknowledge that part of ourselves.” Below, the two have a wide-ranging conversation about hierarchies, hanky codes, and the art of cruising—then and now.

———

JORDAN TANNAHILL: How are you?

ARTHUR TRESS: I’m very well, thank you.

TANNAHILL: First of all, I’ve only seen the book in PDF form, but it just looks extraordinary. The images of The Ramble are so evocative. They seem to be a combination of posed photographs and some that are more kind of documentary in nature. How did the impulse to begin photographing The Ramble emerge?

TRESS: Around 1968, I began a project called Open Space in the Inner City, where you could make parks in different neglected areas of the city, like along the waterfront and old roadways and trails. And of course, I did a lot of work in Central Park, and I happened to live not too far away, at 72nd Street and Riverside Drive, so it was a 10-minute walk. I had been using The Ramble for my own private cruising grounds in a way over the years. One day I just thought it would make an interesting little sociological study on its own. I brought the camera, and some of the photographs of people just walking around were taken a little surreptitiously. But quite often, I’d go up to people and ask them if I could photograph them.

TANNAHILL: And what would their reactions be?

TRESS: Oh, of course some people didn’t want to be part of the project, but other people were fine with it and we’d have a little conversation. My work has always been a little bit of improvised, stage-directed imagery, especially in portraits, so it’s kind of a combination. I call it a sort of “poetic documentary.” I took as the theme the late-winter light, with the bare trees creating a kind of labyrinth of synapses. I felt somehow it was an appropriate leitmotif for the series, so the images had all these kinds of film noir shadow areas in them.

TANNAHILL: Yeah, which is so stunning and evocative. At the time, were you considering these photographs just for yourself, as kind of a private collection? Or did you imagine that they would be shared at some point?

TRESS: Well, at that time, there really was no audience or publications that would show gay photography. They were mostly for myself, but I had a sense that they were historically important. It turns out that it was one of the first documents of gay cruising at a very important fulcrum in time. So I think for your generation, they’re an amazing revelation of a different world.

TANNAHILL: I understand the park at the time in the late ’60s was more derelict and overgrown than it is now. To what extent do you think that was part of the emergence of the park as a cruising space? Had it been, to your knowledge, a cruising space through the ’50s or even earlier?

TRESS: I think it’s funny that even since the 1920s, The Ramble has had a reputation as being a gay cruising place. In the late ’60s, New York was undergoing a kind of economic crisis. That’s why everyone enjoyed living there—it gave the city a rough edge. That part of the park was very overgrown and derelict. There were all kinds of trees falling down, but it was still very interesting and had a certain mood in itself.

TANNAHILL: I’d love to understand more about the stakes for these men at the time, being photographed in what was probably a known cruising space. You mentioned a number of men were comfortable with it. Would they have been comfortable being sort of openly gay men? How concerned might they have been about their image being associated with a gay cruising spot?

TRESS: Well, as a photographer, you develop a certain rapport with your subjects. So I think I just made people feel comfortable with being photographed. In a way, the guys that I met were willing participants. They knew this was something that needed to be recorded.

TANNAHILL: Do you have a memory of the first time you encountered The Ramble?

TRESS: Well, cruising has always been part of New York City life, in all parts of the city. When I was in high school, I’d go down to 42nd Street and you could cruise down by the Christopher Street Pier and along Riverside Drive, by the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. There were different cruising areas.

TANNAHILL: You grew up in Brooklyn, right?

TRESS: Yes.

TANNAHILL: Were you still living in Brooklyn at the time?

TRESS: I was living in Brooklyn with my mother. My father lived at 76th Street and Riverside. So even in high school, when I was out walking the dog at night, I’d try to pick up some man—not too successfully. [Laughs] There was very little information about being gay in those years. One always had a sort of psychological ambivalence about being gay during that time. And I told my father that I was picking up men in the park.

TANNAHILL: You told him?

TRESS: Yes. And that maybe I needed some medical help, because—

TANNAHILL: What did he say to that?

TRESS: I went to see a psychiatrist, and of course he gave me the whole spiel about it being illegal—you could get arrested, it was against nature, it was a mental disease kind of thing. So that made me feel even worse. But I think those feelings were identical to many of the emotions of the men I was photographing in the park when I did The Ramble series. So I think that my photographs are kind of a mirror—a sympathetic mirror—of myself. And I think the models and subjects that I photographed sensed that I had a compassionate understanding for their own struggles.

TANNAHILL: And I understand that earlier in the ’60s, you had traveled rather extensively as an ethnographic photographer, documenting rituals among the Maya in Mexico, the Sámi in Sweden, and the Dogon in West Africa. I’m curious about the extent to which your history as an ethnographic photographer translated to your work in The Ramble.

TRESS: Well, I had been doing this ethnographic photography where I was very concerned with rituals and ceremonies and sites. A great deal of my photography has always been about finding contemporary versions of these worlds—archetypical patterns. Even the work I did here in California in the mid-’90s, with skate parks and paintball fields, explored sites of masculinity. I think that’s always been one of my fascinations—almost a kind of critique of gay masculinity or just masculinity in general.

TANNAHILL: I don’t know if you saw in the news recently, but there has been a crackdown on gay male cruising at Penn Station. There’s a few different locations, the Penn Station washrooms being one. And 20 men among those arrested were detained by ICE and now face extradition, so I’m curious about the policing of cruising over the years. Obviously, cruising has always had its dangers, especially at night. It was interesting that the book notes that a few days before the Stonewall riots, there was a mob of about 20 men brandishing axes and chainsaws that chopped down a known cruising grove in Flushing Meadows. To what extent were the dangers of cruising from residents or from police? And did you ever encounter any of those dangers yourself?

TRESS: Well, I’m really not a night person, and I did feel that to go into Central Park at night during that time period was not a good idea. On a personal level, I had never seen any police arrests or things like that, but I could sense there was an atmosphere of fear and danger. But The Ramble was kind of like a little gay community. There really weren’t that many places like that in 1969. There were the bars, the baths—they were all controlled by the mafia and were very tense, obsessive places. But when you came to The Ramble, it was kind of open and free.

TANNAHILL: Would you recognize regulars or friends at The Ramble, or were they mostly always new encounters?

TRESS: There were regulars, but I never really knew any of them personally. Gay men would walk their dogs there and meet their friends and travel around in little groups. So there were little cliques, even at The Ramble. I would say, “Oh, this is just high school,” all the different hierarchies of young and old, masculine and fat. [Laughs]

TANNAHILL: I was cruising in The Ramble myself on Labor Day, one of the final hot days of summer, and it was just packed. And as you said, there were all kinds of different men there—some in cliques, some in groups, some alone. It felt obviously very primal and feral, but also very social, as you’re saying. But now, in the age of apps, so many men hook up almost like they’re ordering Uber Eats. [Laughs] There’s less of an emphasis on place and chance encounters. And yet cruising does persist. I’m just curious how you’ve observed these changes over the years.

TRESS: I was brought up Jewish, so even when I would be cruising in The Ramble, that probably was why I was never successful. My first question is, “What do you want to do?” [Laughs] But also, “What do you do? Are you a doctor or a lawyer? Can I bring you home to see my mother?”

TANNAHILL: [Laughs] Were you looking for love in The Ramble?

TRESS: Yeah, I was looking for relationships. I always felt that if you like someone, you’d really want to do it again. But of course, it was really the wrong place. [Laughs] And then what happened after Stonewall, particularly, was the evolution of gay institutions where men could meet each other not in a bar, not cruising, but through the Front Runners, gay hiking clubs, the Firehouse gay dances, Columbia student clubs, and gay clubs. I think gay men created this whole set of new institutions where they could meet each other in a more serious and not necessarily sexual way. Actually, in the ’70s and ’80s, there were also men’s therapy groups, because guys did not know how to go on a date. They had no social skills and they didn’t know how to talk to each other. I went to a couple where you’d practice and one of the rules was, “You don’t have sex on your first date,” because you kind of blow the tension in a way and you don’t get to see if you’re compatible with the person. So I’d say there was an evolution from just raw cruising, which didn’t fit my personality. I’m not saying that’s superior to someone who just loves the sexual excitement and energy of, as you say, chance encounters and multiple orgasms. [Laughs]

TANNAHILL: All of these images are, of course, taken before AIDS. I’m curious about what your observation or your lived experience was of cruising in The Ramble at the onset of AIDS, and how that shifted the dynamics within cruising sites in the city?

TRESS: I sort of came out as a gay photographer when I began working for different gay magazines like Mandate and Honcho. I was a staff photographer, because I loved doing erotic fantasies. This is pre-AIDS, so there was a lot of sexual activity all along the New York City piers, particularly. But on a personal level, I had a kind of boyfriend who was an artist for about 10 years. So during the AIDS crisis, I was not personally involved in the cruising scene except as a photographer. I was photographing it from a distance. So I would imagine that the cruising had cooled down and that people were not participating in that kind of accidental form of encounters.

TANNAHILL: At what point did you begin to imagine these photographs for the public and want to share them?

TRESS: Well, around 2022, I began working with Jim Ganz at the Getty Museum, and he was really interested in my work of the late ’60s and early ’70s. I did an exhibit called Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows. I was showing him my pictures of the open spaces and the park and he said, “Well, what are these, Arthur? These are amazing.” And I said,” Well, I shot for a couple of months in The Ramble.” I think all photographers have these little hidden, forgotten chapters in our work that aren’t seen. So I began looking more closely at what was there. I was doing some book proposals to an English publisher and he thought that this would be a very interesting volume to publish. And then we really looked at it more closely and I said, “Well, all of these are amazing…”

TANNAHILL: That’s beautiful. Something that you say in the book which I found really beautiful was that the act of cruising had much in common with photography. You say, “When you’re doing photography, there’s a lot of waiting around for the moment—like one of those white egrets standing in a pond waiting to get the fish.”

TRESS: [Laughs] That’s funny.

TANNAHILL: How much of your process was about waiting around, waiting for something to occur? And how much was it about you being proactive and staging something?

TRESS: In cruising, you’re doing a kind of endless walking around. You’re working a lot with your eyes, looking this way and that way, and then waiting around, a lot of patience. So I think that was always kind of my style of photography. I call them “walkabouts.” I’m in a semi-trance state, and then I suddenly sort of pounce on something. I could almost intuitively identify people who would be sympathetic to me, or people who had such a cold atmosphere about themselves that I couldn’t go up to them. I’m kind of a shy person, actually, so it was kind of a mixture of all those elements.

TANNAHILL: And did your act of photography ever translate into sex? Was the camera an extension of your cruising?

TRESS: Well, a little bit.

TANNAHILL: An icebreaker? [Laughs]

TRESS: It sort of gave me a reason. I was always amazed when I’d look at other gay men—how they could just go up to each other at a bar and say, “Hey, I’m Joe. Can I buy you a drink?” But somehow, it did give me a sort of alibi to go up to these guys. But down the line, it really never worked out, except in maybe one or two instances that I can think of. But it really, really wasn’t the reason I was making the pictures. It was kind of an afterthought.

I think my photos capture a lot of the loneliness and anxiety. And if another photographer came to photograph The Ramble and he had a different attitude towards life, he would photograph people smiling and holding their dogs or all that kind of thing. But I was just very tuned in, because it was a kind of social commentary on the paranoia, anxiety, loneliness, and frustration of gay men at that period. We really don’t like that self-image of the wounded homosexual—The Boys in the Band. But I think now what’s going to make these pictures interesting to people is that we’re ready to acknowledge that part of ourselves—the way we were and still are, at least for a lot of people. So I think the best photos in the series capture that. If you look at the expression in certain people’s eyes, you get that lack of self-esteem. And I photographed that in a very uncensored way. Plus, it was reflective of my own sense of who I was and not being comfortable with my own sexuality.

TANNAHILL: Well, there is something so profound and kind of aching about these photos. So many of these men are captured at this very tender moment in their youth and there’s something kind of melancholy about knowing that many of these men are probably no longer alive. And there’s a real poignancy to those images, I think, in part because of that.

TRESS: Yes. And I know your work a little bit—your recent play. I haven’t seen it, but I hope it comes to San Francisco. But you also seem to be concerned with the different roles that people play. A play that made a big impression on me was The Balcony by Jean Genet.

TANNAHILL: Yeah, a masterwork.

TRESS: And somehow, when you’re photographing gay men, there are all these little sub-genres: the leather guys, the hippies, the clones, the bears. In The Ramble, you sort of have a mixing pot of all these types going by. So I was kind of aware on a social-political level how these different stereotypes that we embrace project a certain kind of image of ourselves.

TANNAHILL: What kind of subcultures did you encounter in The Ramble? And kind of pursuant to that, you mentioned the ethnographic interests in rites and rituals. What were some of the cruising codes that were in play at the time?

TRESS: The hanky code didn’t really come into being until the mid-’70s, so it was mostly some guys who would dress very straight-looking—and of course they were kind of the top, desirable types. And then you’d get older men who dressed a little bit more flamboyantly. But almost everybody was wearing very tight jeans or leather pants. There was a lot of phallic signaling—like rock stars with big crotches. [Laughs]

TANNAHILL: How would they signal?

TRESS: It was just the way people would stand. It was a body language of just standing in a very tense way, or just letting you know that they were there for sex.

TANNAHILL: Would they just have sex there in the open? Or would they go somewhere kind of more secluded and private?

TRESS: Well, it was quite amazing, but there were secret areas of The Ramble that were very overgrown. There were actually even little caves and hidden outcroppings that you could kind of go off to. But I think there was as much rejection, so you kind of wonder if the people were just there just for the act of cruising and really weren’t that interested in sex as much as displaying themselves and parading around.

TANNAHILL: In many ways, little has changed. That all sounds very familiar. [Laughs]

TRESS: Well, that’s what people say. I don’t have a smartphone, but they say it’s the same thing that goes on. Also, it’s very traumatic and psychologically disturbing—these online sites for people. Cruising could be something that diminished your self-esteem, even though it was gays’ defining and owning a space, which was revolutionary in a way.

TANNAHILL: But it could also undermine one’s self-confidence. You could come home from a night of cruising and feel really shitty about yourself.

TRESS: That’s right. I often wish I had all the hours back that I spent hanging around in the back rooms. But occasionally, you would meet someone wonderful in the corner of a bar, a quiet person. But bars were so full of loud noise and cigarette smoke. I don’t smoke, so to hang out in a place like The Ramble was kind of nice.

TANNAHILL: That’s beautiful. I really appreciate your candor, Arthur, and the clarity of your answers. I’d been so looking forward to our conversation and this was so edifying. And congratulations again, Arthur. It’s such a beautiful work and I hope it finds a wide audience.

TRESS: Well, thank you, Jordan. Bye-bye.