Our study demonstrated the predictive value of Lp(a) for new-onset AVC in patients with CAD, and further explored and evaluated other risk factors of AVC.

It is known that higher Lp(a) level is associated with CAD and reduce Lp(a) is undoubtedly an important strategy to prevent CAD in the current treatment. Recently, its correlation with CAVD has made it a focus again. The study of Vongpromek R et al. [11] was the first to reveal the association between elevated Lp(a) and increased risk of AVC. A total of 129 asymptomatic heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia(FH) patients (age 40–69 years) were included, and AVC was detected 38.2% using computed tomography scanning. After adjustment for all covariables, Lp(a) remained an only significant predictor of AVC, with an odds ratio per 10 mg/dL increase in Lp(a) concentration of 1.11 (95% CI 1.01–1.20, P = 0.03). Bouchareb R et al. [12] explained how Lp(a) and valve interstitial cells (VIC) promotes inflammation and mineralization of the aortic valve via Autotaxin (ATX) by Immunohistochemistry studies. Lp(a) transports oxidized phospholipids(OxPL) with a high content in lysophosphatidylcholine. ATX transforms lysophosphatidylcholine into lysophosphatidic acid. ATX-lysophosphatidic acid promotes the mineralization of the aortic valve through a nuclear factor κB/interleukin-6/bone morphogenetic protein pathway, which accelerates the development of CAVD. Furtherly, a case-control study performed within the Copenhagen General Population Study [13], including 725 CAVD cases and 1413 controls free of cardiovascular disease, revealed that OxPL-apoB and OxPL-apo(a) are novel genetic and potentially causal risk factors for CAVD and may explain the association of Lp(a) with CAVD. Capoulade et al. [14]also explored the role of OxPL and Lp(a) as key mediators in the progression of CAVD. OxPL-apoB, which reflects the biological activity of Lp(a), and Lp(a) levels were measured in 220 patients with mild-to-moderate AS, and the annualized increase in peak aortic jet velocity in m/s/year by Doppler echocardiography were measured to determine the progression rate of AS. After 3.5 ± 1.2 years of follow-up, results showed that top tertiles of Lp(a) and OxPL-apoB are associated with faster AS progression as well as increased risk of aortic valve replacement and cardiac death. Those findings above all hypothesis that Lp(a) mediates CAVD progression through its associated OxPL.

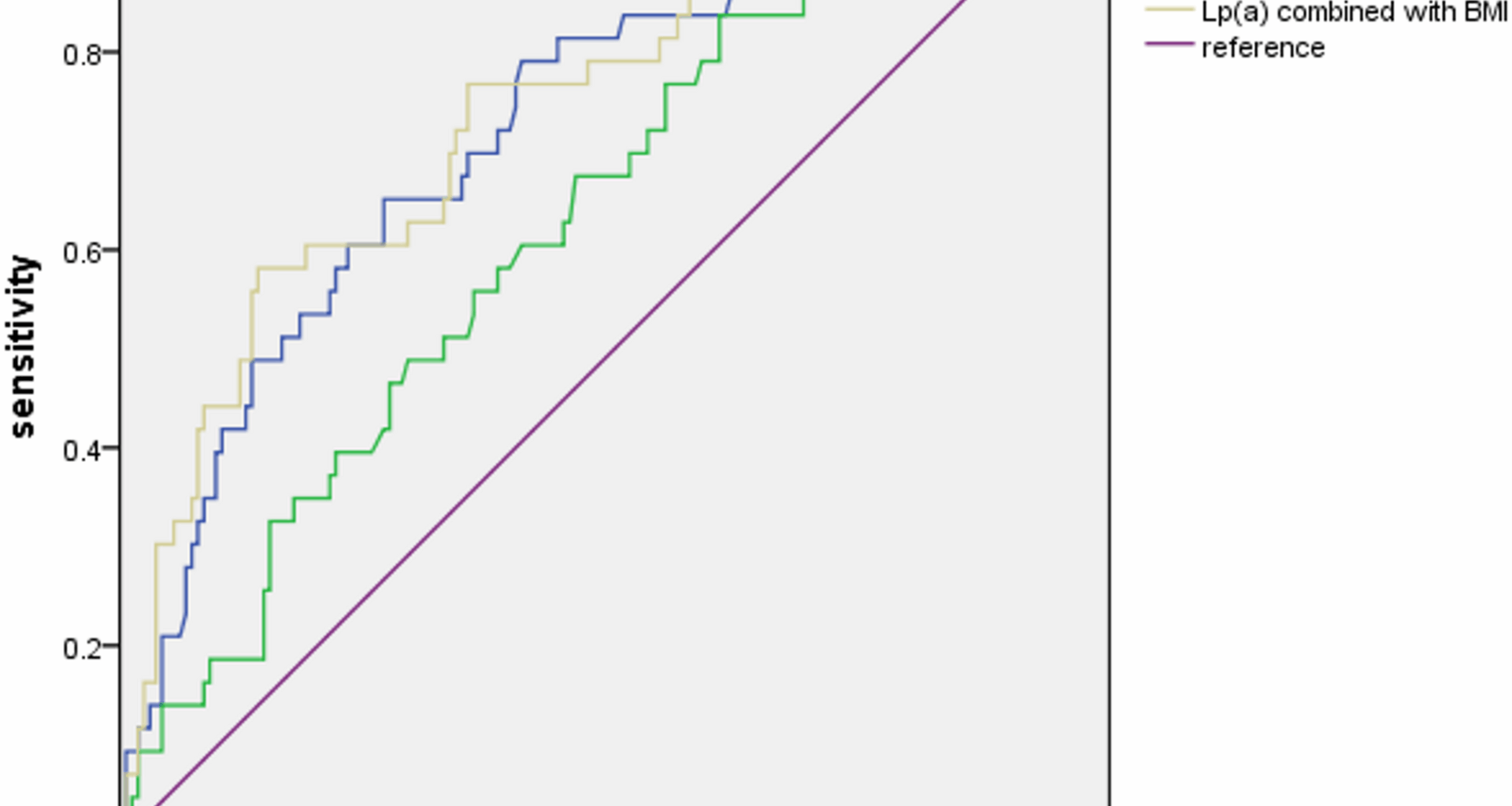

Another convincing and enlightening conclusion comes from the research from the Rotterdam Study [15], which investigated the non-enhanced cardiac computed tomography imaging of totally 922 individuals at baseline and after a median period of up to 14 years. The population-based study finally reported a robust association between Lp(a) and both baseline and new-onset AVC, but it does not correlate with the progression of AVC. This finding seems to indicate that interventions aimed at lowering Lp(a) may be most effective during the pre-calcific stages of CAVD, and explains the failure of statin applying to the patients who have already developed aortic stenosis in previous researches to a certain extent [16, 17]. However, imaging was conducted at only two time points, separated by a 14-year interval, which precludes the identification of the precise temporal onset of AVC. In the observational study by David S. Owens et al. [18], a significant association was identified between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the incidence of AVC over a mean follow-up period of only 2.4 years. It is important to note that the follow-up testing in the study was conducted in two phases. Half of the cohort returned with an average between-scan interval of 1.6 years, while the other half had an interval of 3.2 years. Although it is regrettable that they were not analyzed separately, the study still yielded comprehensive positive results that incident AVC risk was associated with age, male gender, BMI, current smoking, and the use of both antihypertensive and lipid lowering medications. Furthermore, patients with CAD were excluded at baseline. In contrast, our study specifically focused on patients with CAD at baseline. In this population, the pathophysiological response pathway related to Lp(a) may have been activated. Although the average follow-up duration was shorter than that in previous studies, it may indicate that AVC shared a common pathophysiological mechanism with CAD. At present, a handful of trials targeting relevant molecular markers and pathways of the progression of CAVD are ongoing, and the most exciting development may be the recent success of Lp(a)-modifying therapies, particularly the siRNA molecule olpasiran, which has demonstrated an effective reduction in plasma Lp(a) levels during a phase 2 clinical trial [19]. However, there have been no finished studies to verify its clinical effectiveness at present. Our study firstly evaluated the relationship between Lp(a) and AVC in CAD patients rather than the general population or FH patients, and found a still satisfactory predictive value of Lp(a) for new-onset AVC although in the CAD cases who are themselves correlated with high Lp(a) levels, highlighting the important role of Lp(a) as a potential therapeutic target. Further studies were expected to explore exactly efficacious treatments.

There seems a more confusing relationship between BMI and AVC. A Mendelian randomization design [20] included 367,703 UK Biobank participants provides evidence that higher BMI and particularly fat mass index are associated with increased risk of AS. But the study by Mancio et al. [21]came to a different conclusion that BMI and abdominal visceral (VAF) were inversely associated with AVC in AS patients submitted to TAVR. A stratified analysis by obesity showed that in non-obese, VAF was inversely associated with mortality, whereas in obese, high VAF was associated with higher mortality (p < 0.05). This so-called “obesity paradox” challenges the conventional view that obesity always directly leads to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, revealing a potentially more complex interaction between BMI and disease development, particularly in the context of AVC. Our study found that increased BMI remains a risk factor for new-onset AVC in patients with CAD after adjustment for other risk factors (HR 1.195, 95%CI 1.050–1.361, P = 0.007), which may seem different from the conclusions of Mancio et al. However, we included patients who did not get AVC at baseline instead of those submitted to TAVR, who have already suffered severe AVC. In other words, we only confirms that elevated BMI may be associated with new-onset AVC but not progression of AVC. Further studies are supposed to clarify the truth behind these observations to improve management strategies for patients with cardiovascular disease.

There are limited researches directly on the relationship between three-vessel disease and AVC, while the overlap clinical risk factors associated with CAD and AVC such as older age, male sex, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, smoking and so on suggest a potential correlation between them. Additionally, compelling histopathologic and clinical data have shown that CAVD is an active disease process akin to atherosclerosis with lipoprotein deposition, chronic inflammation, and active calcification [5, 22]. In our study, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed an almost double risk of new-onset AVC in patients with three-vessel disease (HR 1.942, 95%CI 1.005–3.755, p = 0.048), supporting the hypothesis for a potentially shared disease process.

Several studies have shown the impact of blood pressure on AVC. Pohle et al. [23] analyzed 1,000 patients using electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) and found AVC was detected more frequently in patients with hypertension (21.7% in patients with hypertension vs. 13.9% in patients without hypertension; p = 0.01). Shinichi Iwata et al. [24]indicated an independently association between diastolic (both mean awake diastolic BP and asleep diastolic BP) and advanced calcification of aortic valve leaflet in their study consisted of 737 patients underwent 24-hour ABP monitoring. The prospective study by Lionel Tastet et al. [25]confirmed that systolic hypertension is associated with faster AVC progression. But hypertension was not observed as a risk factor for new-onset AVC of patients with CAD in our study (HR 1.341, 95%CI 0.6888–2.616, P = 0.389). The reason may be that CAD is known associated with hypertension already, so that the positive impacts of hypertension become relatively reduced in this population. However, we found that an increase in LVPW was an independent predictor of new-onset AVC (HR 1.390, 95%CI 1.084–1.782, P = 0.009). It is known that the most common reason of thickened LVPW is increased pressure load due to high blood pressure, so it cannot be ruled out that the relationship between LVPW and new-onset AVC shown in our study may be partially mediated by hypertension.

There are numerous findings underlining the critical role of diabetes in the progression of CAVD. Letitia Ciortan et al. [26]developed a 3D model of the human aortic valve based on gelatin methacrylate and showed that hyperglycemia accelerated the progression of CAVD by inducing inflammation and remodeling mechanisms in valvular endothelial cells (VECs) and VICs. The research by Magdalena Kopytek et al. [27] furtherly revealed that type2 diabetes enhances in loco inflammation and coagulation activation within stenotic valve leaflets via upregulated expression of both NF-κB and BMP-2. Khai Le Quang et al. [28] verified the evidence that the dysmetabolic state of type 2 diabetes mellitus contributes to early mineralization of the aortic valve and CAVD pathogenesis through established the diabetes mellitus -prone LDLr(-/-)/ApoB(100/100)/IGF-II mouse as a new model of CAVD. In our study, univariate Cox regression analysis showed that diabetes increase the risk of new-onset AVC (HR 2.118, 95%CI 1.161–3.861, P = 0.014) of patients with CAD but not an independent predictor in multivariate cox regression analysis. This may be due to the fact that diabetes is also a clear risk factor of CAD, which confused the result. More clinical trials and experimental researches are needed to reveal the complex progression of inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic abnormalities in the pathogenesis of CAVD with diabetes.

There are unavoidable limitations in this study. Firstly, we employed echocardiography to identify AVC, which may exhibit lower accuracy in comparison to computed tomography scanning utilized in numerous more rigorous studies, thereby potentially constraining the validity of our research. Secondly, the study was a single-center, observational study with a relatively small sample size, which may undermine credibility. Thirdly, calcification of the valve is considered a long-term process, while the follow-up time of our study seemed to be relatively short. Lastly, we only investigated the association between Lp(a) and new-onset AVC in patients with CAD, but failed to declare its prognostic value.