There were many reasons why, a bit over a year ago, a supposedly retired Bill Bryson found himself sweating in a cave on the side of a Gibraltar cliff and wondering how Neanderthals might have hunted tuna.

But the primary reason was a website. It was a website someone had written in his honour. Sort of.

Bryson first heard about the website seven years earlier at a book signing. It was 2017, he was in Australia, and a reader approached him. In the years since writing A Short History of Nearly Everything he had written five other books. Yet that book — the most successful popular science book of the 21st century — still followed him.

And now he learnt there was a website devoted to it. But not in a wholly good way. “It was all the things that were wrong,” he says. “People just randomly contributed to it.” It was a sort of Wikibryson for pedants.

Bryson with his wife, Cynthia, at Wimbledon, 2013

ALAMY

The website was hard to find (thankfully, perhaps), but he persisted in tracking it down. Then he braced himself and had a read. To his annoyance, it had a point. “Some of the things they found were definitely wrong.” In his defence, his book was 180,000 words long, attempted to tell the entire story of science, and was written essentially pre-internet. So this wasn’t surprising.

• Bill Bryson: Too many people publishing their own books

“When I wrote it, if I wanted to know how many moons Jupiter had, I had to get dressed and go to the library and find a book. And you know, even in a good library it might be five years old.”

But, also, most of the mistakes weren’t actually his mistakes. They simply reflected the fact that science had moved on. Since he wrote the book we have discovered: four kinds of archaic human, one Higgs boson, one novel coronavirus and well over 5,000 planets outside our solar system. We have also lost one planet in our solar system: Pluto. That was something of an issue for the chapter about Pluto.

A quarter-century after he had first surprised (and not entirely pleased) his editor by suggesting a pivot from writing whimsical bestselling travelogues to investigating the history of ideas, maybe it was time for an update?

He knew what to do. He booked the ticket to Gibraltar.

Never say never again

There is, by now, something of a formula to Bill Bryson interviews. In 2019, aged 67, he wrote his final book, The Body, and gave his last round of publicity interviews. In 2022, aged 70, he wrote his final final (audio) book, for Audible (they “made me a very attractive offer, as they tend to do”, he said at the time), and again explained in interviews that this would be the last time he would talk.

Last year he slightly apologetically gave an interview in The Sunday Times. The first words were: “Eighteen months ago, in these pages, Bill Bryson gave his last interview.” That really was, Bryson said, his “last, last” interview. After it was over, he would be heading home to potter around his four-acre Hampshire garden, holiday with his 12 grandchildren, and keep his views about British customer service, litter and civility to himself for evermore.

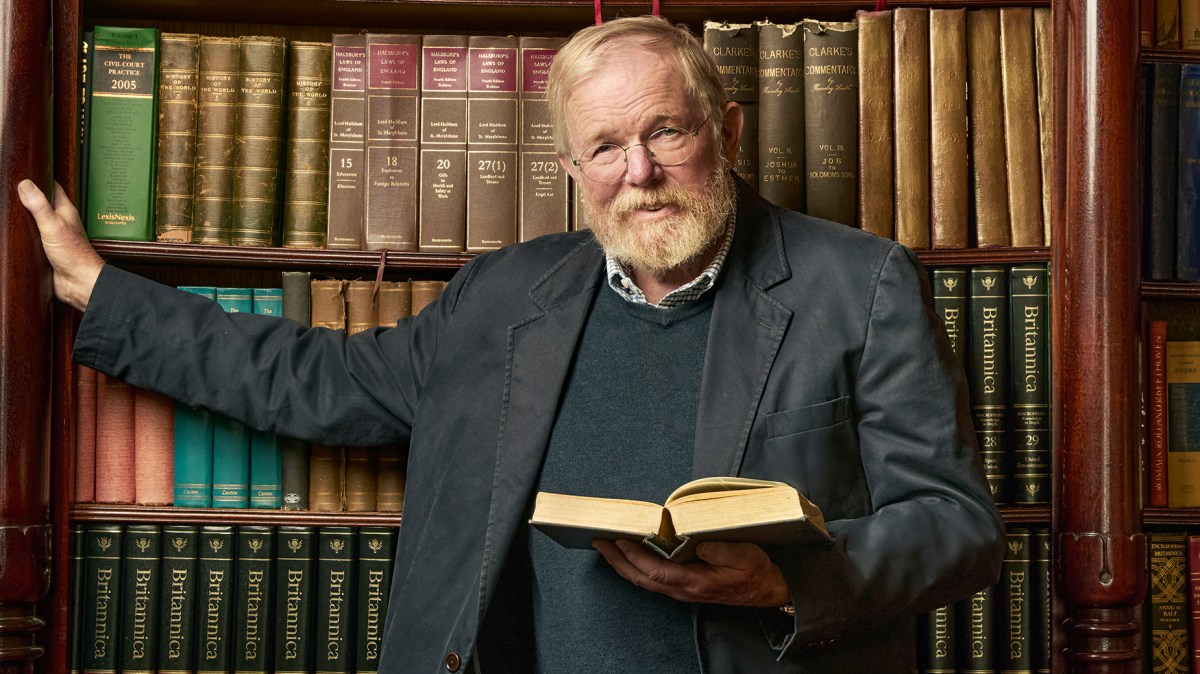

“One of the good things about the British is that they tend to be very self-critical”

JUDE EDGINTON FOR THE TIMES MAGAZINE

So naturally, here we are again. We are sitting in the bar of the Gore hotel, round the back of the Albert Hall. It is a Tube strike day and he has had to walk here from his London flat. I have had to cycle here from Paddington. After all this effort, will he assure me this time I’m definitely not going to read someone else interviewing him in another year?

• World’s top scientists are hoping for the best cold call of all

He promises me he will be faithful. At almost 74, this really is his last interview. Although. “I really sincerely promised Bryan Appleyard that that was going to be my last. Nobody else would ever talk to me again for print.” That was, for the record, two interviews ago. “And I really meant it.” But this time? “This time I mean it too.”

There is at least a passing possibility, then, that this will also be the last time that we will hear him explain why he went from writing books predicated on “finding new countries and getting drunk and making a fool of myself” to books predicated on, say, the intricacies of the Great Devonian Controversy.

More importantly, given the present political situation, it is just conceivable it is the final occasion we will persuade him to do one of his perennially popular turns — explain, to our national mystification, why he actually thinks Britain is sort of all right.

An American by birth, a Brit by choice, Bryson came to fame here through the strangest love letter to Britain — Notes from a Small Island. This slim travelogue was not just about a Britain of jam and Jerusalem, of stately homes and sceptred isles, dreaming spires and misty churchyards. It was also a travel book suffused with the grey drizzle and glutinous baked beans of a Dover guesthouse. And yet, it was also affectionate. Here was this foreigner who knew what we were, who had seen us at our worst and yet, mysteriously, liked us. Through him we found a way to say that, maybe, Britain is OK after all.

Then, we liked to hear him repeat it. In 2003, he praised us for being “slightly cynical, always looking for a joke”. He liked the “gloom and a willingness to embrace defeat… The way to poleaxe a Brit was to tell them they were better at something.” In 2016 he lamented that like America we had become more greedy and selfish. But, he added, we “haven’t quite mastered it yet”. Broadly, he still thought we were OK.

With Robert Redford for the premiere of A Walk in the Woods at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival

SHUTTERSTOCK

‘Britain is still devoted to decency and common sense’

Now here we are again, a decade later. The Tubes aren’t working, Britain isn’t working; there is a consensus we are doomed. I feel we need some Bryson positivity. He hesitates slightly. He has, he said, just spent a morning on hold to his bank trying to get them to unblock a debit card. “You know, you’ve got to spend 40 minutes just to exhaust an algorithm, before you can speak to a human.” There are, he concedes, modern annoyances.

“There are so many things in Britain that have deteriorated. But nothing like what’s happened to my own country. And that’s not just Trump. When I go back to Iowa and just see what’s been lost and what has not been preserved that was good, it would be hard for me to be positive.

“I really do genuinely still think that Britain is, on the whole, a really terrific country. There are more frustrations now than previously perhaps. There’s less consideration for others now, but this is still a country that’s pretty devoted to decency and common sense.”

And whatever deterioration he has seen in the public sphere has been more than offset by improvements in the culinary one.

He first saw Britain in the damp twilight of Dover — arriving in a town with an almost implacable opposition to providing him goods and services in exchange for money. When he did find someone who would take his cash it came in the form of a formidable landlady called Mrs Smegma who, he wrote, “surveyed me critically, as she might a carpet stain, and considered if there was anything else she could do to make my life wretched”.

Today, things are better. “When I first came here you would really see articles in magazines that would say things like, ‘It’s summertime, time for mayonnaise.’ ” He does jazz hands, to emphasise the mayonnaisey excitement. Back then, in 1973, he was backpacking, and even with the inducements of mayonnaise wasn’t intending to stay. But he found himself seduced — not just by our potato salads, but by a nurse. Two girls he knew worked in a psychiatric hospital and, over the course of a drunken night in a pub, said they could get him a job as an orderly. He took up the offer, and while making beds there met Cynthia.

So he stayed. Later, he found that the skills he developed — doing the thankless heavy lifting for mentally unstable people — transferred well to being a sub-editor at The Times. His writing career had begun.

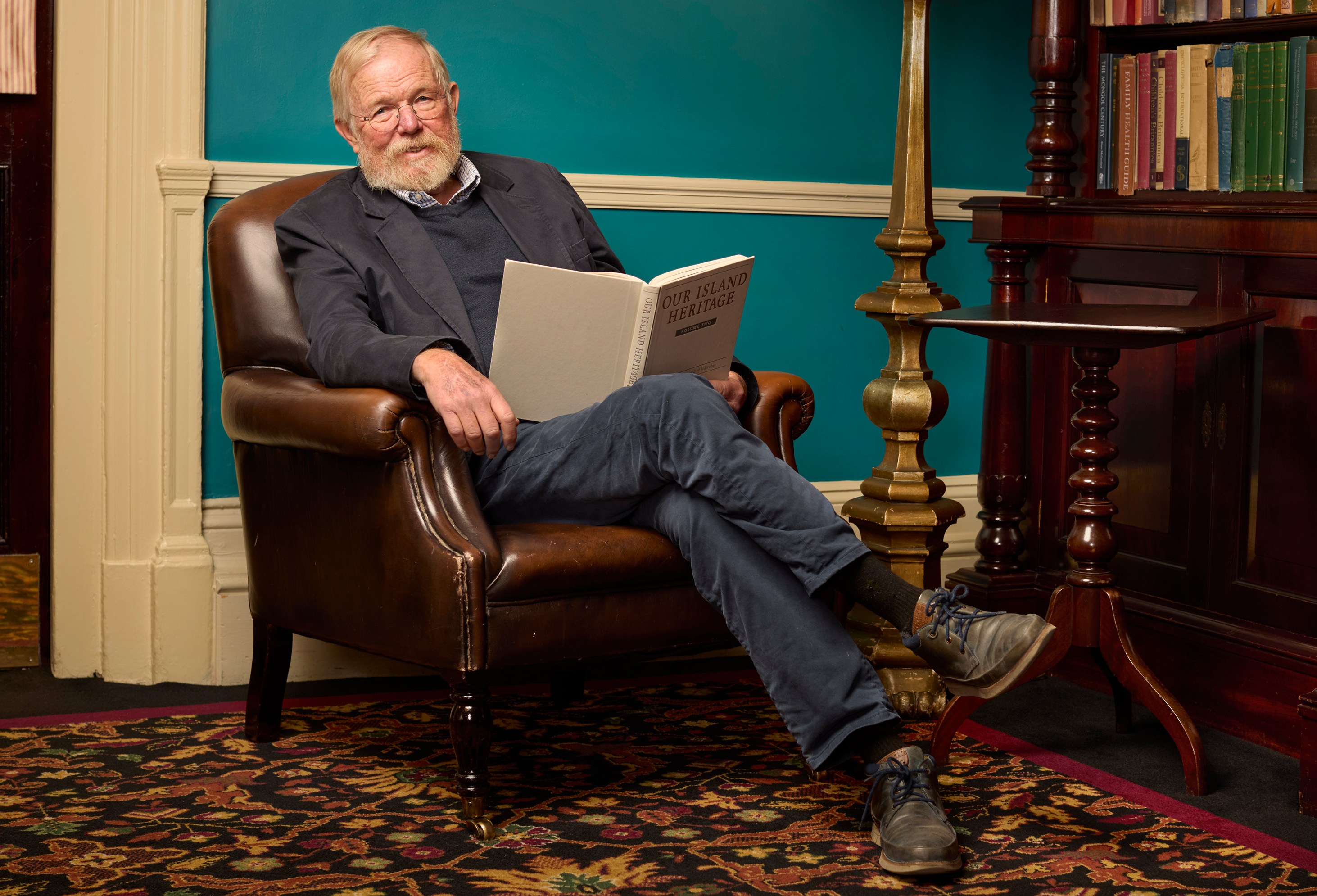

“Neanderthals were probably just as smart as we were”

JUDE EDGINTON FOR THE TIMES MAGAZINE

The evolution of evolution

It is not just Britain that has changed unrecognisably in the past decades. Science has too. And nowhere more so than in our understanding of where we all came from. In 2003, the year A Short History was published, something else was published: the human genome. We had, for the first time, the code to life.

It would be crucial, in ways we didn’t begin to anticipate. In 2008, at around the time Bryson had moved on to a book researching a history of domestic life, there was a discovery that concerned the domestic life of humans. But it wasn’t a Homo sapiens sort of human.

In Denisova cave in Siberia, scientists found the smallest sliver of a finger bone. Other scientists extracted DNA from that finger bone — using technology that was exponentially cheaper and exponentially better than that from just five years earlier. What they revealed was one of the greatest scientific discoveries of the 21st century: this cave had been the home of a new kind of human, the Denisovan.

Thanks in large part to DNA, we now know we walked the earth with many other intelligences like us, but not us — the genus homo, today containing just one member, was brimming with life. And we know, again because of DNA, we had sex with them. If you are ethnically European, 1 to 2 per cent of your DNA is Neanderthal. If you are southeast Asian, a similar proportion is Denisovan.

Of all the chapters in the book, it was the one about human evolution that required the most updating.

So it was that, one day last year, Bryson found himself taking a break from his retirement — from Cynthia, now his wife of 50 years, his garden in rural Hampshire, his duties towards his 12 grandchildren and his duties towards litterpicking the local verges — and heading to Gibraltar.

What he found was a last redoubt of Englishness — just the sort of place he would have written about in a different life. “It really is just a little English seaside village in the Mediterranean.” But that wasn’t the book he was here to write.

Here, I need to declare some conflicts of interest. The first is that I get an acknowledgment in the updated A Short History. Bryson and I both write books for Penguin Random House, and after a decade as the Times science editor they asked me to help out with topics that needed updating and fact-checking (when Wikibryson gets new entries, I’m partly to blame). So I’m invested in the book.

The second COI pushes in the other direction. Professionally, as a science writer, I find the book very annoying. It’s not just that Bryson is that vanishingly rare thing: a nonfiction author who makes lots of money. It’s also that — I say this through gritted teeth — he deserves to. Time and again, Bryson finds a phrase or anecdote that I wish I had found.

As an example, here is a sentence that made me look at life completely differently. “It is a slightly arresting notion that if you were to pick yourself apart with tweezers, one atom at a time, you would produce a mound of fine atomic dust, none of which had ever been alive but all of which had once been you.”

The publisher, of course, has been delighted that Bryson has come back — to pick apart the atoms of his last book and put them together to make something new. Nothing warms the cockles of Penguin Random House’s accountants more than a turn from a bankable star they had assumed was retired.

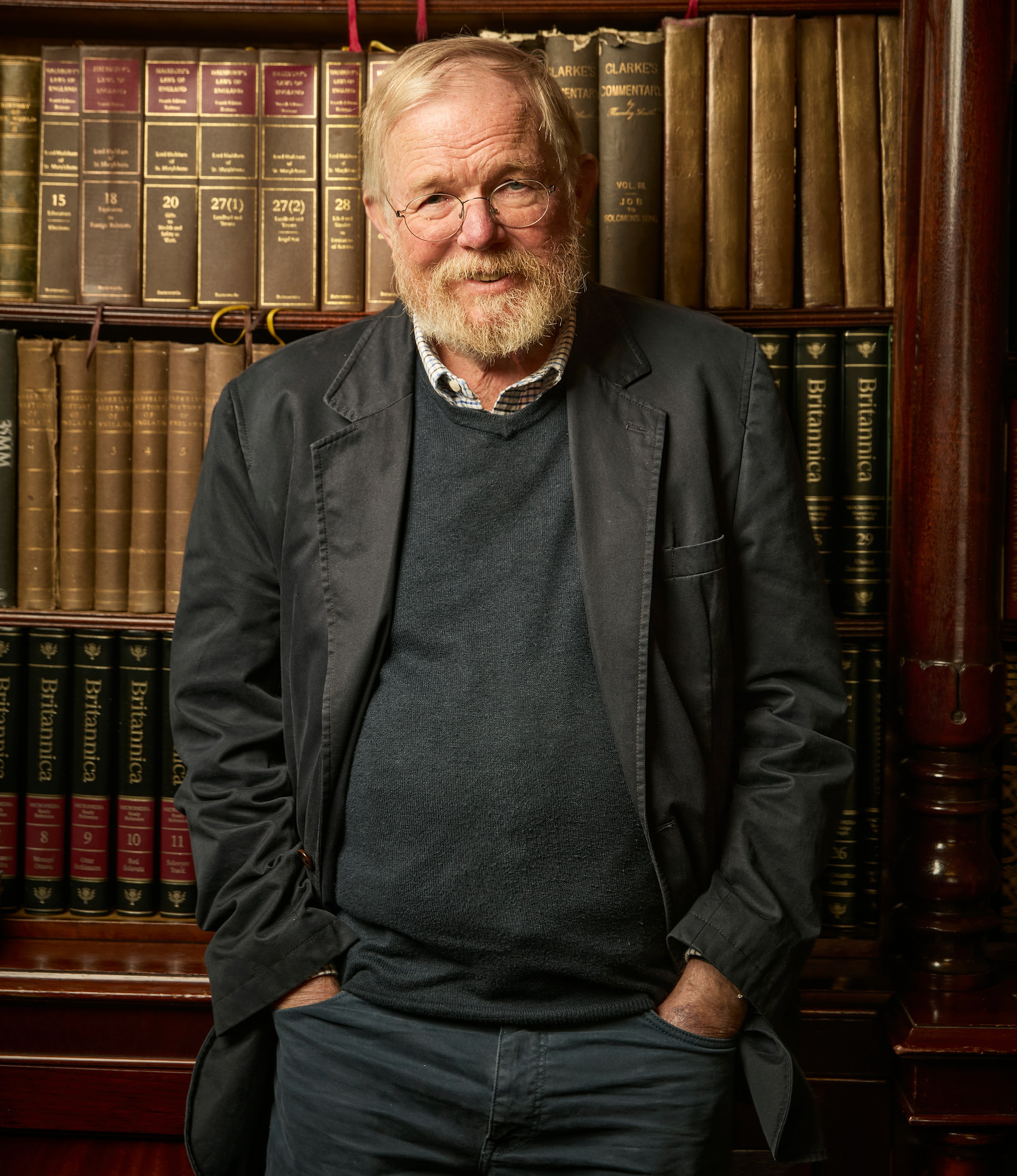

“Americans think everything is as good as it can possibly be, even when it’s shit”

JUDE EDGINTON FOR THE TIMES MAGAZINE

The first time round, his editors were less keen on his puzzling interest in science. A Short History was not a Bryson book. After touring round Britain successfully, in the Nineties he had toured round all manner of other places successfully. He had taken public transport and had whimsical capers, gone for long walks and had whimsical capers. He had become a whimsical travelogue caper person.

Then, “I went to my editor in America and said, ‘OK, now I want to do a book where I’m trying to understand science.’ And he said, ‘No. You do hiking books now. Why would you throw that away? Just get your friend and go off and do the Pacific Crest Trail or something.’ ”

“I said, ‘But that’s just the same book.’ He said, ‘Exactly.’ ”

‘I don’t want to waste the time I have left’

His editor was, obviously, wrong. A Short History wasn’t only popular among readers, it was popular among scientists. Bryson is now an honorary fellow of the Royal Society. He name-drops Nobel laureates who are now his friends.

So on that trip to Gibraltar he eschewed the postboxes, mock Tudor cottages and monkeys, with all their possibilities for whimsical capers and enjoyable anachronisms. He continued until, on the southern tip of the rock, he reached the sort of place he writes about now: the last redoubt of the Neanderthals.

For 100,000 years, our evolutionary cousin lived here. The detritus of its meals — partridge, pigeon, fruit, nuts, dolphins and tuna — littered the ground. It’s possible that here, where Europe meets the Atlantic, is also the last place Neanderthals lived — the site of their extinction.

For Bryson, it represented a counterfactual. “They were probably just as smart as we were. These ones in Gibraltar were probably the most comfortable humans on Earth at the time. They were living very well, and there wasn’t any reason if they had survived that they wouldn’t be our equals or superiors today.”

It also represented a last hurrah, a reminder of why he wrote. Did it make him think, perhaps, that there is another book in him after all? Absolutely not.

“It sounds gloomy, but when you get to a certain age, you do realise that you don’t know how many years of being active and feeling good you’ve got left. I don’t want to waste it. I want to be selfish about it.”

In that case, any final words of comfort for his adopted country? “It’s never as bad as people think it is. One of the good things about the British is that they tend to be very self-critical. And that means that you’re constantly attuned to things not being the way they should and actually inclined to try to make them better.

“Whereas I think Americans are the opposite — they think everything is as good as it can possibly be, even when it’s shit.”

And that’s his last last word. The interview is done, the book is done, and grandchildren and gardens await. This time it really is over.

“I just sent off the last corrections yesterday. So, I think I’m now completely finished with it.” He has stopped. He is aware, though, that science has not. Already, the book is becoming out of date. “You know, if they discover the source of dark matter tonight, I’m f***ed.”

A Short History of Nearly Everything 2.0 by Bill Bryson (£25, Doubleday) is published on October 21. Order from timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK P&P on online orders over £25. Discount for Times+ members