In 2004 Ben Stiller was his own billion-dollar business. It was extraordinary. From the frat-bro romps Anchorman and Dodgeball to Meet the Fockers, Along Came Polly and Starsky & Hutch, he was the undisputed king of comedy. That year was no blip, either. There’s Something About Mary (1998), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Zoolander (2001) — if you laughed at the turn of the century, it probably had something to do with Stiller.

Yet one person was not in on the joke — Stiller’s mother. “She was a tough audience,” Stiller says, as we talk about his mother, Anne Meara, a successful comedian, who died in 2015. “People would say how proud she was, and she always told me she loved me, but she would often name some great director and ask if I could do a film with them. And it affected me — because I wanted to do that stuff too, and was trying to figure out how.”

We meet in Los Angeles, at the celebrated A-lister hotel Chateau Marmont. Stiller is 59 and the absolute opposite of his live-wire screen presence — calm and softly spoken. He settles on the sofa and, after an icebreaker about his beloved New York Knicks, gets into discussing Stiller & Meara: Nothing Is Lost, the unique documentary that he has directed.

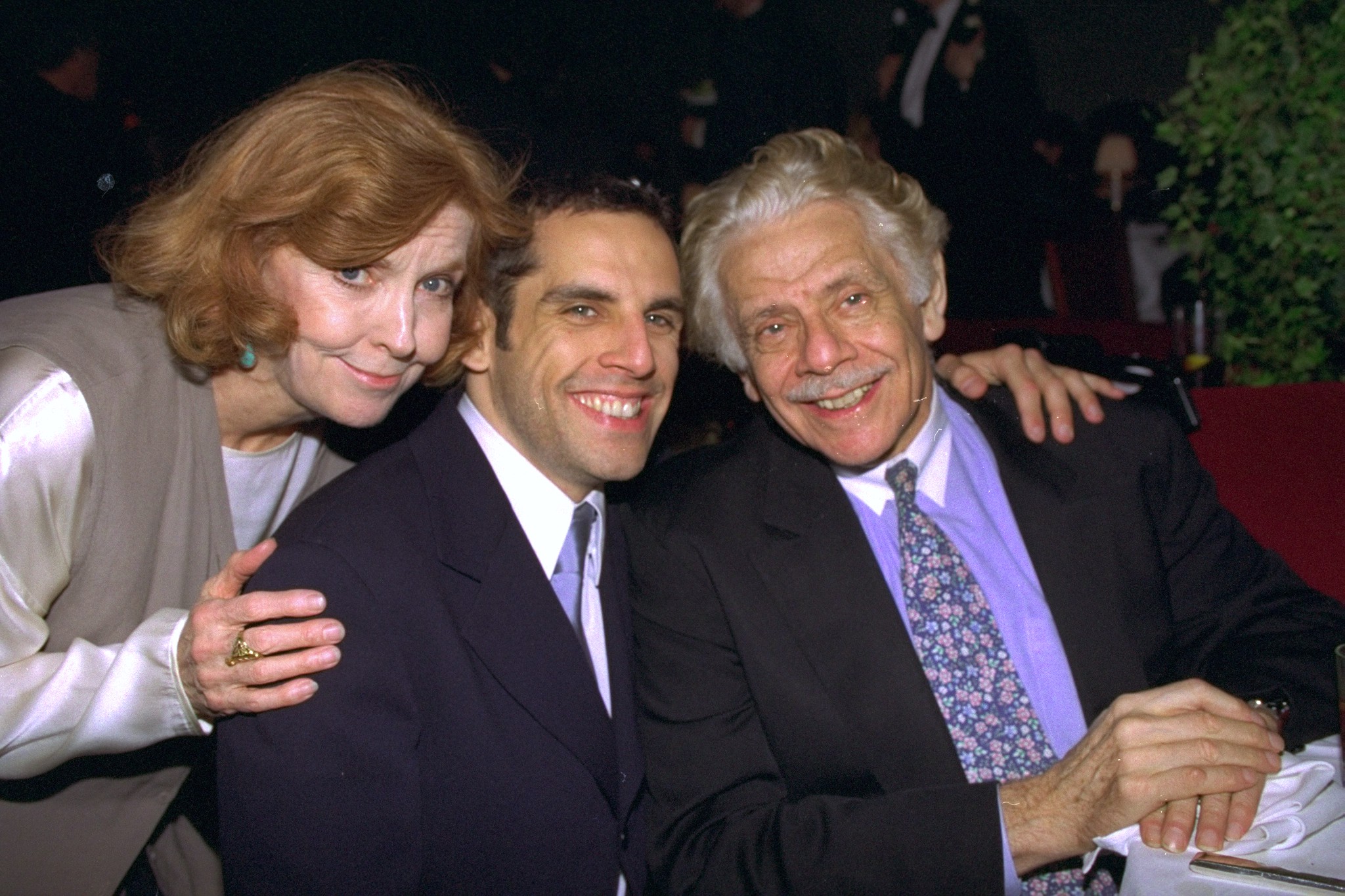

Stiller with his parents, Anne Meara and Jerry Stiller, in 1996

RICHARD CORKERY/NY DAILY NEWS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

It is about his complicated relationship with his parents, Anne and Jerry Stiller (another comedian — he played George Costanza’s dad in Seinfeld). Stiller has directed a lot recently. He shoots the excellent satire of modern life Severance, back for a third series next year, and behind the camera is where he always wanted to be.

• Could Severance really happen? We’re not far off, neuroscientist says

His new film is 90 minutes of emotional toll, and speaking to him I feel less like an interviewer and more like Stiller’s therapist, as he dives into everything from how he feels he let down his own children due to the impact his parents had on him, to the collapse of his marriage.

I mention an interview from 1994, when he had a big break with Reality Bites — a Gen X classic comedy that he starred in and directed. In that article he said he really wanted to focus on directing but, just four years later, he was in the rom-com There’s Something About Mary and his comedy onslaught began. Was his entire career an accident?

“A little, yes,” he says with a grin. “It is not how I imagined it, for sure. Those roles were fun to get swept up in, but I wanted to be a film-maker.” Was he fulfilled? “Yes, but also a bit conflicted — I wanted other stuff. Just before There’s Something About Mary, I auditioned for a supporting role in Face/Off [John Woo’s action film] to play a role that went to Alessandro Nivola. I had a couple of callbacks, but didn’t get it.”

He now thinks his mother’s ambivalence towards his comedy success came from her own ambitions. “It’s interesting to see this from my mum’s perspective,” he says. “Because she might have been thinking more from her own experiences than from mine. She didn’t really get much opportunity to do the serious stuff that she wanted either.”

Stiller & Meara is a beautiful film about family, memory, love, loss, ambition, regret and comedy. Non-US audiences cannot grasp the popularity Stiller’s parents enjoyed — Jerry and Anne formed a double act in the 1960s that would perform to 12 million people on The Ed Sullivan Show. Yet there were frequent difficulties in their careers, with cancelled TV shows and slogging endlessly round the circuit to make a living. Jerry, who died in 2020, was a prolific chronicler of it all. His home movies form the bulk of the documentary.

“I just had to make something for my parents,” Stiller explains. “My dad died during Covid, so there was no memorial. When my mum died, five years earlier, we did an event on Broadway, and so I felt pressure.” Does he know why Jerry recorded at the rate he did? “I don’t — and I was never smart enough to interview them when they were alive.”

When sifting through the footage, Stiller was most surprised about the chat shows his parents went on during their heyday. There was one, The Mike Douglas Show, which was on daytime TV — a 1960s version of The One Show, perhaps. “My dad is talking about my mum’s drinking,” he says with a gasp — Anne would drink to levels that shocked Jerry. “About how she passed out on the coat pile at a party at my cousin’s house. People were much more raw. You don’t get that on TV now.” Anne just laughs along.

Anne and Jerry in The Stiller and Meara Show

AL LEVINE/NBC UNIVERSAL/GETTY IMAGES

One scene that stayed with me was from 1974 — when Stiller was nine. His parents took him and his elder sister, Amy, on a talk show to play their violins. They are not great. “You’re being kind. It’s cringey,” he says. Anne and Jerry both sit on the couch, laughing. It seems cruel?

“I don’t see it that way,” Stiller says. “They just wanted to fill that segment, choose a skit. They thought that it would be cute and I never felt they were trying to exploit us. They were just trying to be entertaining.”

Stiller came out of it well — or as well-adjusted as any comedian can be. His sister, however, struggled. She wanted to act too, but was drifting, waitressing, while her little brother became rich and famous. “It was f***ing hard,” she admits in the film.

“She had a tough road,” Stiller says. “There have been ups and downs.” Which is no surprise: Anne and Jerry’s double act had them as a rowing couple, and when they were rehearsing behind closed doors, their kids could not tell if they were acting or actually arguing.

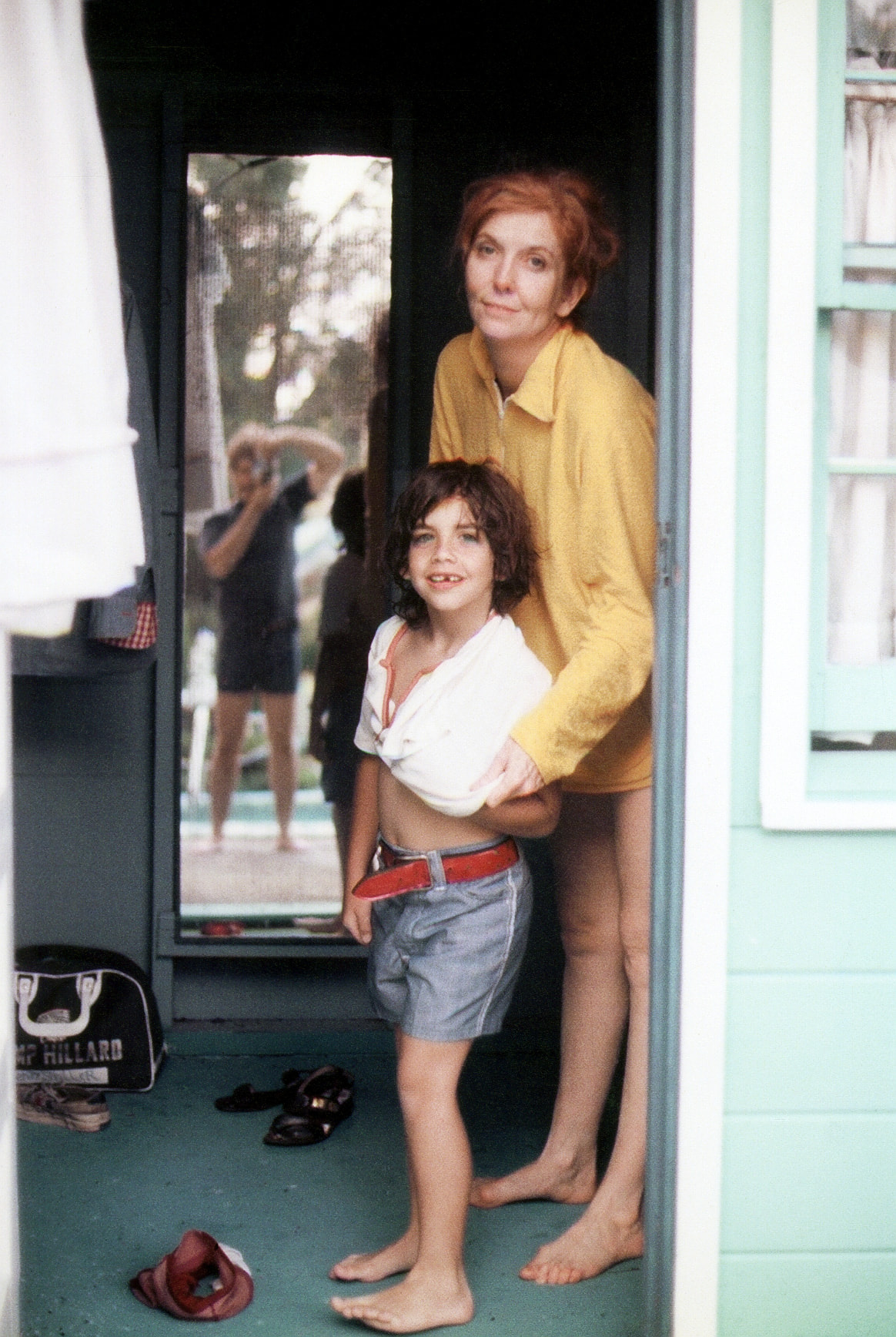

Stiller with his mother in 1973

APPLE TV+

“It totally affected us,” Stiller admits. As working comedians, Stiller’s parents had to gig late or leave home in New York for weeks on end in Los Angeles. “I just remember missing them terribly,” Stiller says. “And when they would come back, my sister and I would act out Jesus Christ Superstar or something in the lounge.” He frowns.

Shrugging, he moves on to talk about his own family. “But, then, I probably f***ed up more with my kids than my parents did with us.” I gasp a little. Stiller has Ella, 23, and Quinn, 20, with his wife, the actress Christine Taylor, who starred alongside him in Dodgeball and Zoolander.

There is a lot to unpick in their family dynamic. For instance, he gave Ella a role in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which he directed, only to leave her on the cutting-room floor. “My son tells me that being a dad might not have been at the top of my list,” Stiller says, shaking his head. Part of the problem was that when Stiller was at home in New York with his family, his head was elsewhere, which is exactly the issue that he remembers with Anne and Jerry.

• The 20 best films and TV shows about Hollywood ranked

“Like any parent, I remember things that weren’t happy about my childhood and go, ‘I’ll do better,’” he says. “And then I realised it was impossible to avoid making the mistakes they made. I feel like I have a really great relationship with my kids, but it’s complicated and has at times been strained. When they were young, I did not get it. I thought, ‘Oh, the kids are young, I can work away and be a good dad earning for the family.’ But the bonds you form with your kids when they’re young are so important.”

In 2017 Stiller and Taylor split up, getting back together in 2020 when the family reunited during the pandemic. “That was a strain on my relationship with the kids,” Stiller says of their separation. “And I’d think, ‘Well, my parents never did that.’ But a long relationship is hard. You lose the freshness. I feel bad about what us breaking up did to the kids, but it was possibly the best thing to happen to Christine and me.

With Christine Taylor and their children, Quinn and Ella, in 2013

BROADIMAGE/SHUTTERSTOCK

“It changed our relationship. We don’t take it for granted any more, and if you are happy, you’re going to be a better parent. You have hurdles and try to figure it out, and if you stay, all you can do is acknowledge the past and try to repair. That’s what we have in our family. It’s not perfect — at all. But that’s just life.”

Stiller’s career is in something of a purple patch. The Emmy-winning Severance has made him the acclaimed director that he always wanted to be, while next year will bring the fourth in the Meet the Parents series, Focker In-Law. That film feels like an anomaly — a broadbrush comedy like the ones that earned Stiller a fortune but are now barely made. He nods. “For whatever reason, people going to the cinema for a comedy stopped being a thing.”

“Maybe the tone they had in the 2000s was just of its time?” he continues. I say that I rewatched Zoolander and knew that certain jokes about, for example, people’s appearance, or the entire country of Malaysia, just would not be signed off now. “Yes, there are landmines everywhere.”

Is that why broad comedies have gone — the jokes are too risky? “Twitter changed everything. It took off in 2009, and offers an immediate response.” An immediate damning? “Yes, because we had issues on Tropic Thunder with Simple Jack.” He means the boy with intellectual disabilities he plays in the spoof. “It wasn’t a Twitter storm. Everything didn’t blow up. But instant reactivity can now, all of a sudden, just kill.”

• Read more film reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

Does that make comedians stop trying? “Yes, you’re more trepidatious, and there’s no denying the environment is more volatile, but when studios keep saying no, creatives will stop trying and, instead, pivot to movies they think will get made, and that’s awful. Studios are trying to create movies that will make a billion dollars, but comedy is cut and dried. People are laughing or not. And that’s tough.”

Which Stiller certainly knows from his mother. I think of his new documentary — would Anne and, indeed, Jerry have liked what he made about them? Their son shuffles awkwardly — looking a little vulnerable. “I have these conversations with myself at night,” he admits. “Dad would have reservations with regards to how we talk about Mum’s drinking, but, then, he was very protective of her. But I feel she would have been fine — because she was always very open.”

He grins. For all Stiller’s honesty about their difficulties, it’s a gorgeous tribute. A paean to the pain — and joy — of families that resonates far beyond Hollywood. At one point Jerry simply says that Anne is the most wonderful person he has ever met, and that sums it up. His parents knew, and now Stiller does too, that life is full of ups and downs, but it is also full of love.

Stiller & Meara: Nothing Is Lost is out on Oct 17. Times+ members can celebrate the release with an exclusive screening at selected Everyman cinemas across the UK on Tuesday, Oct 21, only. Visit thetimes.com/timesplus for more details