Trigger warning: this article might offend people who like trigger warnings.

A study is just the latest to suggest that telling people they are about to experience offensive content does not seem to change their behaviour — and could even make them want to watch it.

Researchers in Australia found that during the course of a normal week, young people came across trigger warnings on social media dozens of times. Sometimes these came in the form of text, cautioning them that a post contained distressing content. Sometimes it was blurred images or video that they had to then consent to see.

But whatever the variety of sources of the warnings, the response to them was largely the same: irrespective of whether or not people said they suffered from trauma, they were ignored.

The study, published in the Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, found that of the 261 participants, 90 per cent of them happily clicked through, and some said they were more likely to do so precisely because of the warning.

Crucially, those who reported suffering from trauma were no less likely to click. One even told the researchers it was an inducement, saying: “Sometimes my brain wants to be triggered, so it grabs my attention more.”

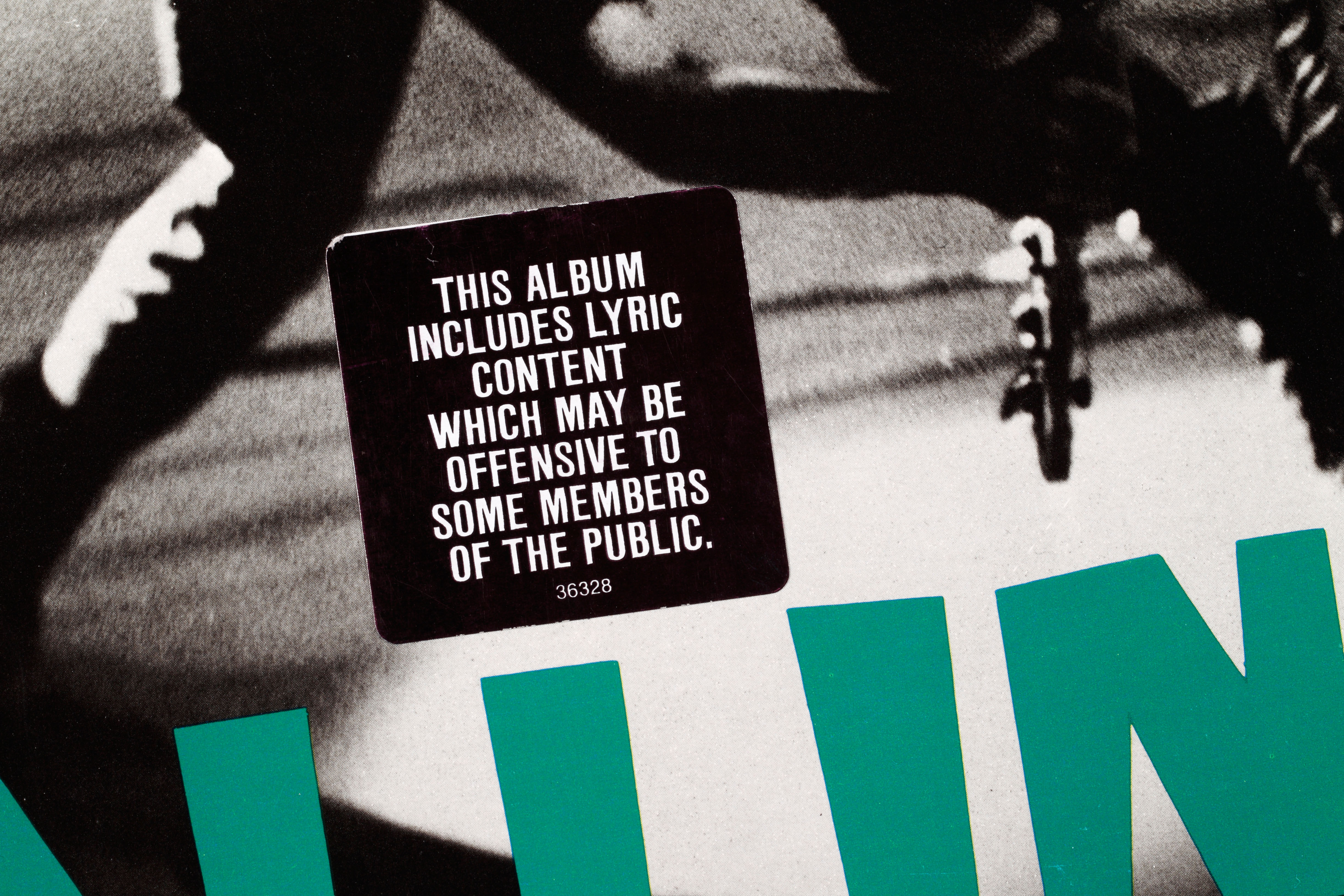

The album London Calling by the Clash has been branded with a warning

ALAMY

Victoria Bridgland, from Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, said that she was not surprised by the findings.

• Edinburgh Festival trigger warnings risk giving away the plot

“There’s a lot of political baggage in this conversation. This typically skews between two viewpoints. On one side it’s that trigger warnings are coddling people, and students are snowflakes. On the other side, it’s that we need to make accommodations for trauma survivors.”

Her interest, she said, was simpler: do they work? Do they change behaviour, and do they help when they do?

There has now been a decade of research into this, of which her study is just the latest. “They all come to the same conclusion. Trigger warnings don’t really change people’s behaviours or emotions at all. I’m quite certain that the warnings don’t emotionally prepare people.”

Work in laboratory studies has found that among the most consistent responses is — as in their real world study — to be intrigued.

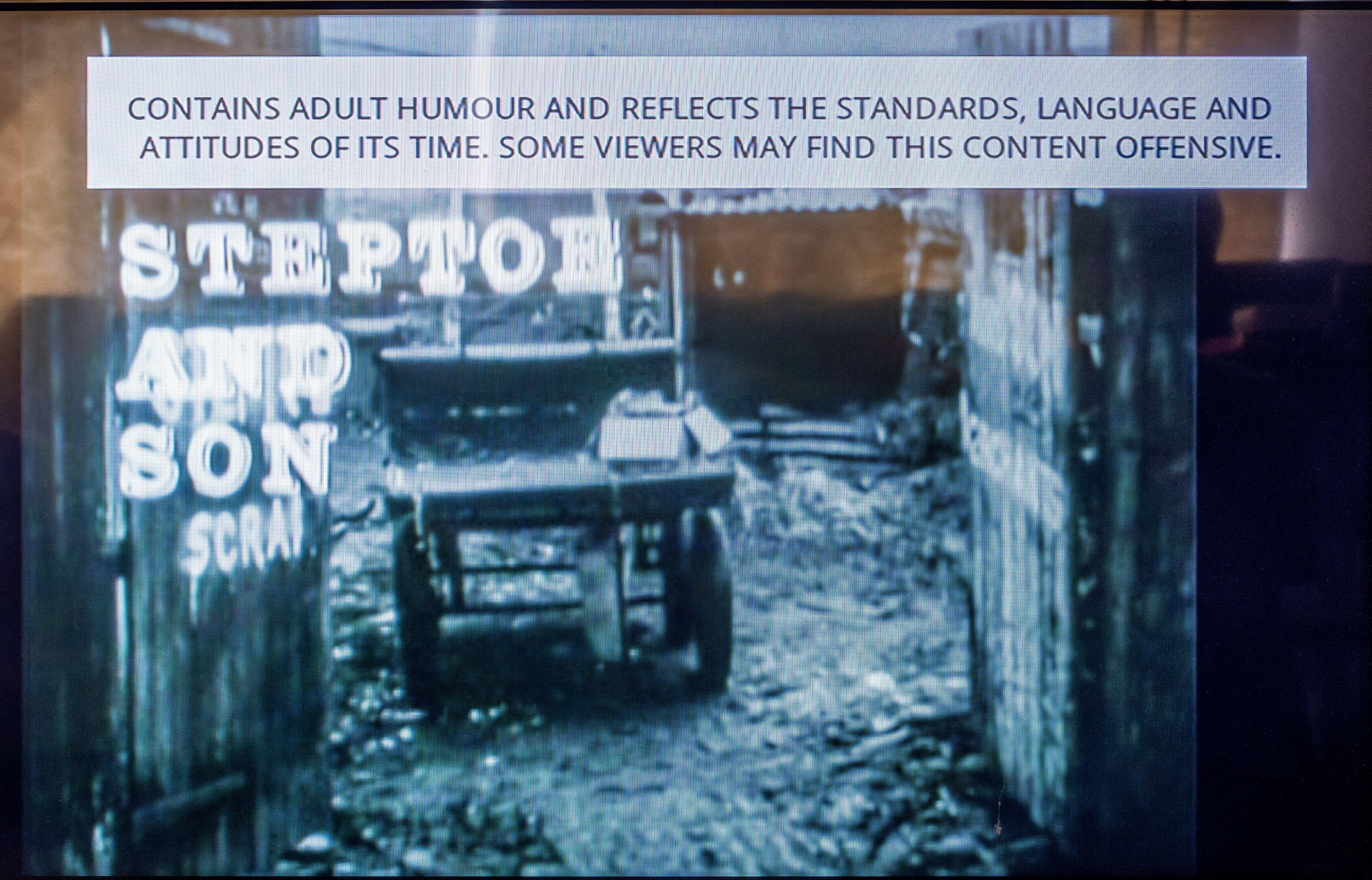

The comedy Steptoe and Son also features a trigger warning

ALAMY

“The problem with most trigger warnings in the studies that we’ve done so far is that most of the time, in practice, trigger warnings are quite vague, and so they create curiosity.”

But, she suspects, amid the proliferation of trigger warnings there is one constituency they do serve: the organisations that post the content.

“What’s the utility of sharing a beheading video, for instance? It’s not going to raise awareness more than telling people a beheading happen, but it’ll get clicks.

“So they put a warning on it, to be like, ‘We warned you, if you’re going to watch the graphic content and be disturbed by it, that’s on you.’ But they’re going to show you this graphic stuff because they know it’s going to get clicks.

“Trigger warnings are there to put the onus back on the consumer. Instead of a news organisation being responsible, they put a warning on it.”