Credit: ZME Science/Midjourney.

Credit: ZME Science/Midjourney.

Look up on a clear night, and you might catch a strange kind of light show. A glowing streak of light, moving slower than a meteor, disintegrates piece by piece. That’s not a comet or a shooting star — it’s a Starlink satellite burning up in the atmosphere as it crashes back to Earth.

You may have seen the deluge of Starlink satellite breakups that have recently flooded social media. According to astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, these events will soon become a daily routine.

“There are currently one to two Starlink satellites falling back to Earth every day,” McDowell said during an interview with EarthSky.

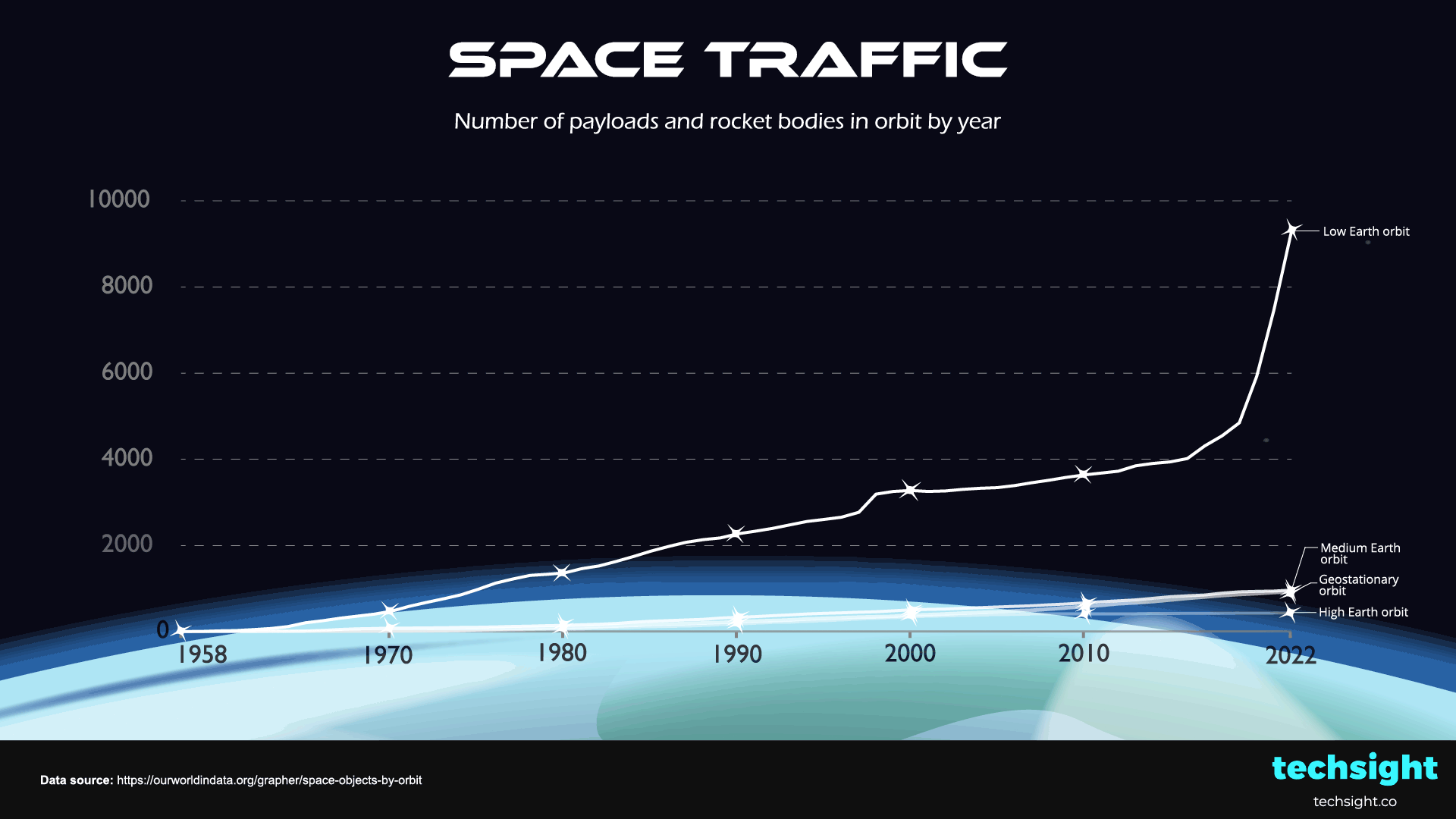

With nearly 8,000 Starlinks orbiting the planet — and thousands more being launched by SpaceX, but also its competitors — McDowell estimates that in a few years, as many as five satellites could reenter Earth’s atmosphere each day.

A Growing Cloud of Trouble

This is the dirty secret of our gleaming, space-age internet: each Starlink satellite lives fast and dies young. Designed to last about five years, these machines orbit in what’s called low Earth orbit (LEO), roughly 340 miles up — close enough to still feel 95% of Earth’s gravity. To stay aloft, they fire thrusters loaded with krypton or argon gas. When that fuel runs out, they naturally begin to fall.

SpaceX insists the descent of its Starlink satellites (which have grown in size from the size of a small table to that of a car) is harmless. “They [Starlink satellites] are designed to completely burn up,” McDowell said. “Now we’re not sure we really believe that they really burn up, but at least for the most part they melt.”

In 2024, a 2.5-kilogram chunk of a Starlink modem enclosure crashed onto a farm in Saskatchewan, Canada. SpaceX had guaranteed that it would vaporize completely. It didn’t, and the 5-pound debris lying in a farmer’s field proved it. Since then, more fragments have fallen — to Poland, Kenya, North Carolina, and Algeria. Such incidents are only bound to increase.

Right now, around 80% of all satellites in LEO belong to SpaceX, which plans to deploy up to 42,000 units. By comparison, Jeff Bezos’s Project Kuiper plans about 3,200, while China’s GuoWang and Qianfan networks could add another 18,000. The European Space Agency predicts that by 2030, 100,000 low-orbit satellites will crowd the skies.

As each satellite burns up, it releases clouds of metal vapor made of aluminum, lithium, copper, and lead into the stratosphere. As a result of more frequent launches, human-made satellites have nearly doubled natural metal aerosol levels in the upper atmosphere. These metals could damage the ozone layer.

“Almost no one is thinking about the environmental impact on the stratosphere,” Atmospheric chemist Daniel Murphy warned in an interview with Science.

Currently, about 2,000 satellite reentries per year emit 17 metric tons of aluminum oxide nanoparticles into the stratosphere. That’s not a whole lot. However, multiply that by 10 or 20 as the low Earth orbit (LEO) broadband internet satellite fleet expands. Now, you get a new kind of significant pollution: anthropogenic meteor showers.

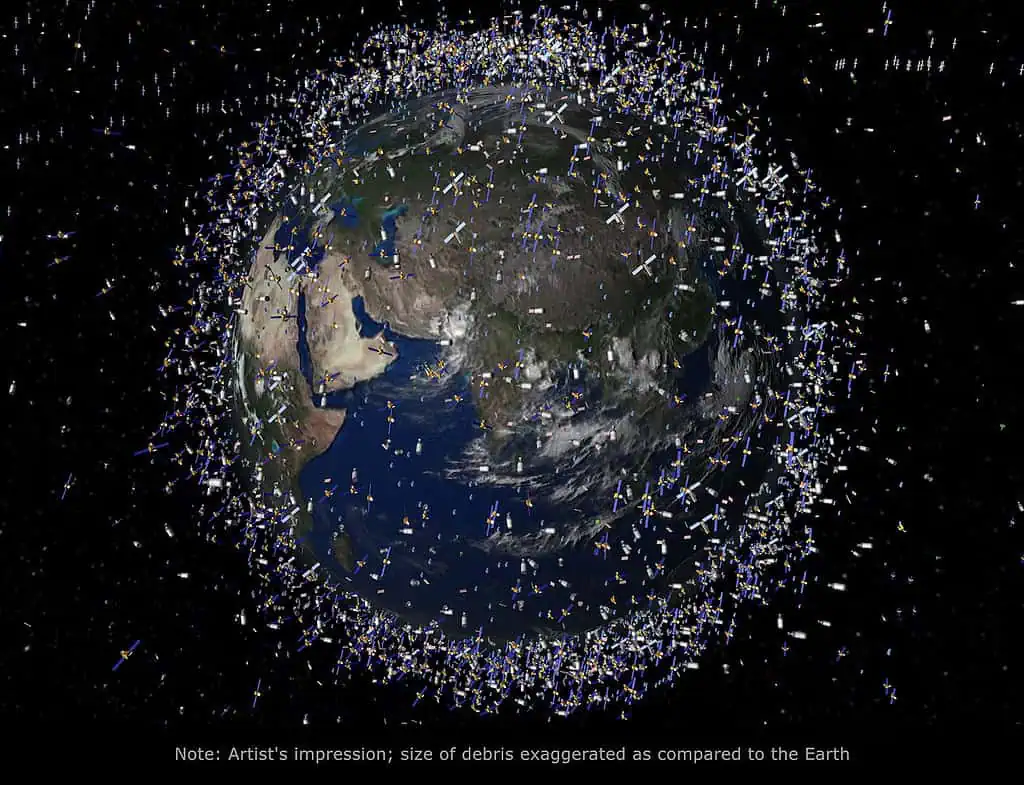

Then there’s the risk of what scientists call Kessler Syndrome, a chain reaction where one orbital collision triggers thousands more, filling Earth’s orbit with lethal debris. The end stage of this phenomenon is that no launches into space are feasible anymore unless the “space junk” is cleared, which may prove to be impossible beyond a certain threshold.

The debris field shown in the image above is an artist’s impression based on actual data. Credit: ESA.

The debris field shown in the image above is an artist’s impression based on actual data. Credit: ESA.

The risks are lower for Starlink’s current orbit, about 340 kilometers up. Any debris is naturally pulled back down within a few years. But Starlink’s orbital neighborhood is already the most crowded region in space, in the vicinity of our planet, and even a small crash could unleash thousands of fragments that slice through nearby satellites before they, too, burn away.

Starlink already has to perform collision avoidance maneuvers every two minutes. If a solar flare, cyberattack, or human error disables those systems for even an hour, the dominoes could start to fall. Add to that the higher-altitude constellations planned by China and others, where debris can linger for centuries, and you start to see the real danger: a chain reaction that begins low, spreads high, and turns near-Earth space into a scrapyard glowing faintly in the dark.

Billionaires, Regulation, and a Burning Sky

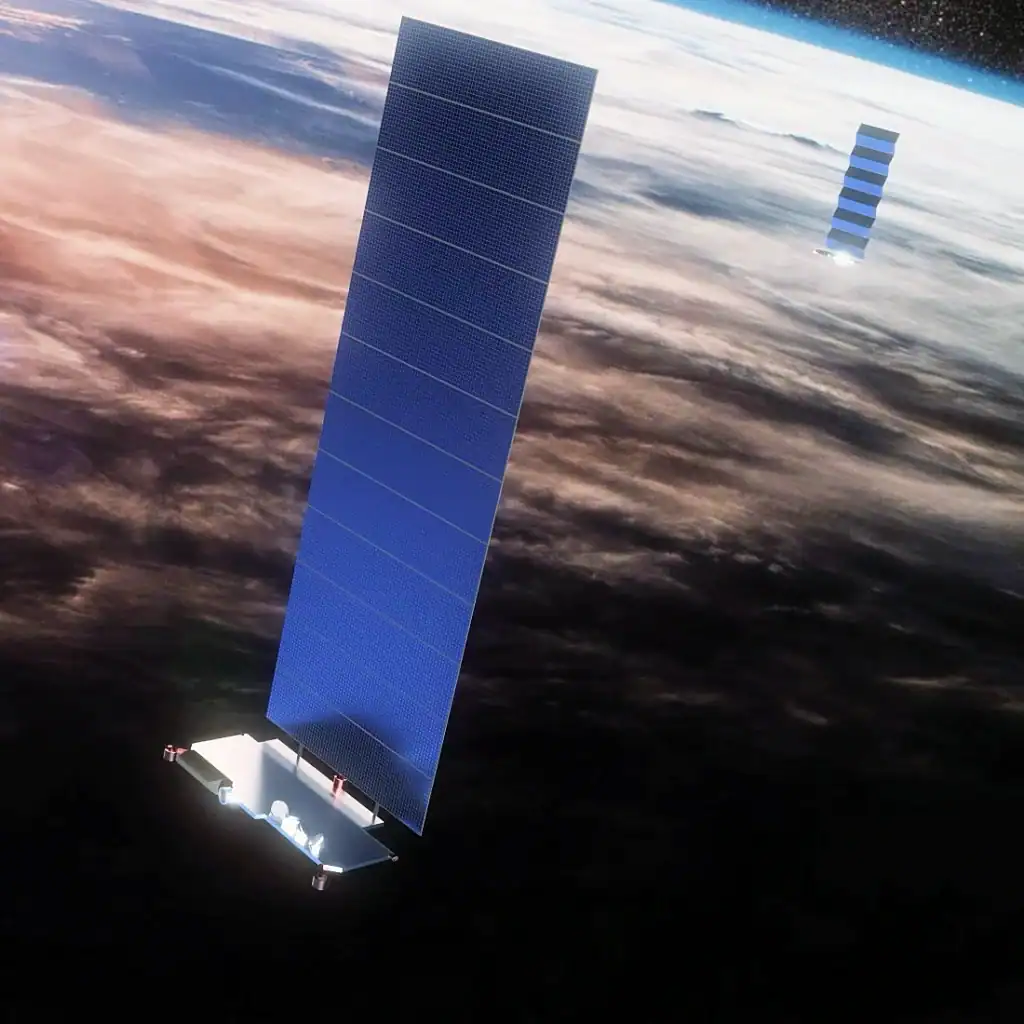

Illustration of Starlink satellites deployed in Earth’s low orbit. Credit: ISPreview.

Illustration of Starlink satellites deployed in Earth’s low orbit. Credit: ISPreview.

There’s something almost feudal about how space has been divided up by billionaires with rockets.

Back in 2021, Josef Aschbacher, head of the European Space Agency, warned the Financial Times: “You have one person owning half of the active satellites in the world. That’s quite amazing. De facto, he is making the rules.” Aschbacher was referring of course to Elon Musk.

SpaceX insists it uses redundant safety systems. They also claim that the risk of human injury from falling debris is “less than 1 in 100 million.” But that doesn’t account for the slow-motion fallout, such as the the creeping accumulation of metallic dust and orbital wreckage circling above us.

Without international limits on how many satellites companies can launch — or on how they must safely dispose of them — the skies could become permanently scarred.

As astronomer Samantha Lawler recently wrote in an opinion piece for Live Science, “LEO is a valuable resource that must be protected and shared in a way that benefits the most people while simultaneously protecting LEO for use by future generations.”