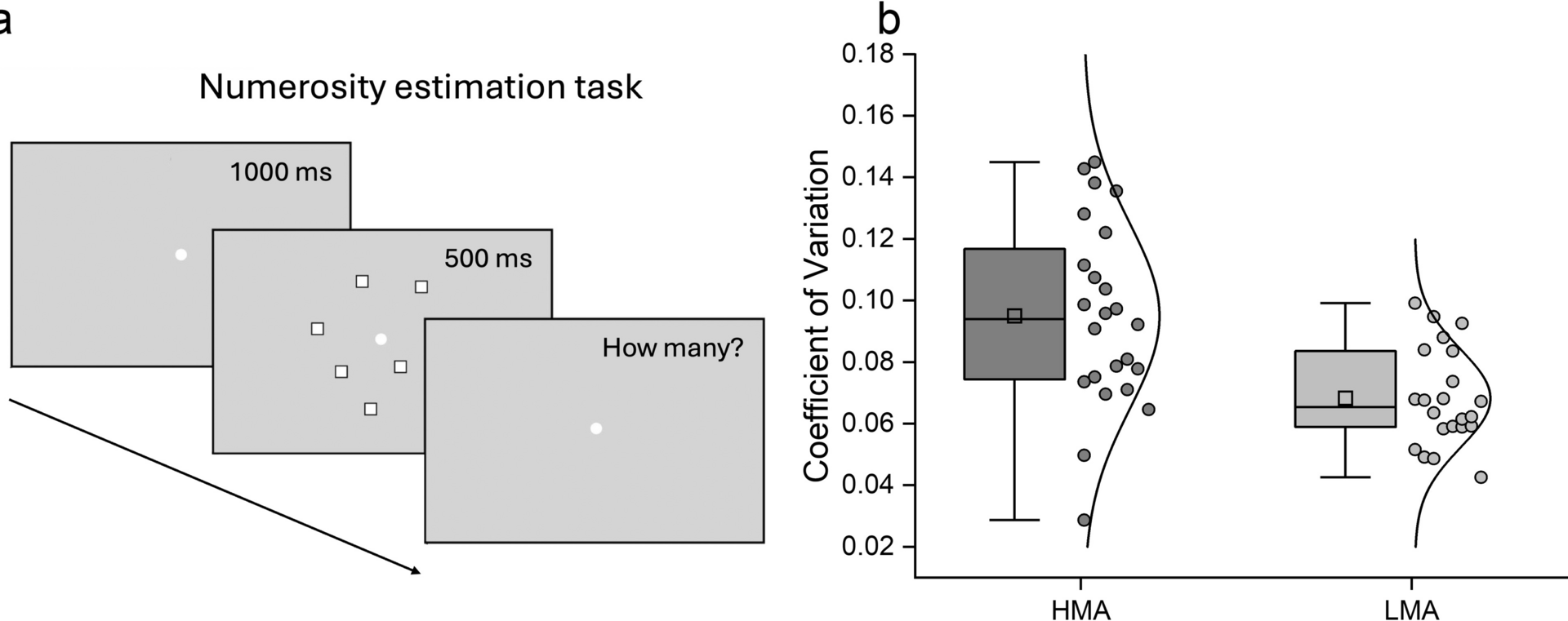

There is now substantial evidence that current perception strongly depends on previous stimuli, as in the case of serial dependence and central tendency phenomena. While these “history effects” have been observed across a wide range of tasks and sensory features, their underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In the current study, we asked whether one possible source of variability in history effects lies in individual differences in psychological traits, specifically anxiety. We found that participants with higher levels of math anxiety relied more on past stimuli, showing stronger central tendency and serial dependence in a visual numerosity task compared to those with lower levels of math anxiety.

This finding aligns with a growing body of research suggesting that affective experience plays an active role in shaping perceptual processing, rather than being a mere post-perceptual reaction [52, 53]. For example, goal-directed motivations can bias size perception: thirsty individuals tend to overestimate the height of a glass [54], and nicotine-deprived smokers tend to overestimate the length of a cigarette [55]. Other affective states, such as stress and relaxation, also affect visual perception: stress increases susceptibility to visual illusions [56], whereas meditation has been shown to reduce their strength [57, 58].

Particularly relevant to the present work, anxiety has been shown to influence early stages of visual processing. For instance, Phelps and colleagues [59] found that briefly presenting a fearful face prior to a tilted Gabor patch improved orientation discrimination, and that this effect could not be reduced to a mere shift in covert attention. Since orientation discrimination relies on contrast sensitivity, this suggests that emotional cues can enhance low-level visual perceptual mechanisms. In a subsequent study, the same group investigated how this effect is modulated by trait anxiety [60]. Individuals with high-trait anxiety showed impaired contrast sensitivity at the target location when attention was captured by a fearful face presented elsewhere, indicating greater difficulty in disengaging from threat. Anxiety has also been shown to affect other perceptual processes, such as time perception. For instance, Liu and Li [61] grouped participants based on trait anxiety, induced either a calm or an anxious state, and tested their reproduction of 2-s duration words. They found that high-trait anxious individuals underestimated duration, while low-trait anxious individuals overestimated it in the anxious compared to the calm condition.

The present study contributes to this literature by demonstrating that math anxiety can modulate reliance on prior stimulus history during numerosity perception. Notably, the strength of history effects among individuals with high versus low math anxiety was predicted by interindividual differences in sensory precision, as measured by the coefficient of variation. This suggests that the influence of math anxiety on history effects may be mediated by diminished sensory precision.

These findings fit well with previous studies showing that the magnitude of central tendency and serial dependence are both predicted by sensory thresholds [9] and are most evident under conditions of higher sensory noise, such as in cases of deprived attentional resources [36]. The link between history effects and perceptual uncertainty has also been reported for perceptual properties beyond numerosity, such as time [8, 34], length [35], or orientation perception [62, 63]. For instance, in an orientation reproduction task, Cicchini et al. [62] found that history effects scaled with stimulus sensory uncertainty: less precisely encoded stimuli (e.g., low spatial frequency, obliquely oriented Gabors) exhibited stronger serial dependence compared to easier stimuli (e.g., cardinal orientations). Furthermore, fMRI research has shown that the sensory uncertainty driving serial dependence is mirrored in the probability distributions decoded from visual cortex activity [63].

More generally, the findings of the current study support the account that frames history effects as perceptual biases influencing the phenomenological appearance of visual stimuli [12, 64]. According to this “perceptual” account, past visual information is integrated with the current percept to reduce noise and generate a “continuity field” that promotes visual stability over time [12, 13]. Consistent with this idea, previous studies on numerosity perception have shown that serial dependence effects display typical characteristics of low-level sensory processes, such as being spatially/retinotopically localized to the position of the inducer stimulus [19, 21]. These effects persist even when post-perceptual processes are minimized by the stimulus presentation procedure, such as when the stimuli to be compared are presented simultaneously rather than sequentially to minimize the involvement of working memory [21]. Moreover, an EEG study found that early visual evoked potentials (VEPs) elicited by dot arrays were systematically biased by the numerosity of the preceding stimulus, even in passive-viewing paradigms, thus independently of decisional processes [22]. Taken together, this evidence points to a perceptual nature of serial dependence in numerosity perception.

On the other hand, previous research has shown that serial dependence intensifies as the temporal delay between stimulus and response increases, suggesting that history effects arise from post-perceptual processes [45, 46]. Additionally, both central tendency and serial dependence are modulated by memory load [47,48,49].

Although the current study is limited by measuring WM proficiency solely through the Corsi test [50], we found that the coarser sensory precision observed in HMA participants, rather than their WM span, was the key factor explaining their stronger reliance on past stimulation. These findings could not be explained by differences in reaction times between groups, either, and therefore not by differences in WM retention time. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that history effects are primarily perceptual rather than mnemonic phenomena.

However, at least for serial dependence, the two accounts may not be mutually exclusive and could potentially be reconciled. Research has shown that the transition of a visual percept into WM leads to a loss of sensory precision [65]. Consequently, prolonging the retention interval between stimulus and response could reduce the reliability of the current sensory input, potentially explaining some effects attributed to the WM/decisional stage [45, 46]. This hypothesis aligns with the Bayesian model, which suggests that when the current stimulus is less precise, reliance on prior knowledge—and consequently, history effects—increases [2, 66, 67]. Yet, perceptual and post-perceptual/memory biases may coexist and jointly interfere with current perception. Much evidence suggests that serial dependence in numerosity perception exhibits several hallmarks of high-level processing. For example, serial dependence effects have been observed even between memorized stimuli and regardless of their presentation order [24]. Moreover, history biases in numerosity perception depend on attention and are amplified when participants attend to the inducer stimulus [20, 21, 28]. These biases also require stimulus awareness, as they are suppressed when backward masking prevents conscious perception [26, 68]. In addition, the effect occurs regardless of numerical format (e.g., the number of sequential visual flashes biases the perceived numerosity of dot arrays [23]), although it does not impact different sensory modalities (e.g., acoustic stimuli [23]) or different stimulus dimensions (i.e., inducer numerosity biases subsequent perceived numerosity, but not perceived duration [29]). A subsequent study showed that both symbolic numbers and feedback on numerosity estimates induced serial bias in dot arrays presented in the following trial [27]. Finally, using the connectedness illusion, a recent study found that serial dependence acts on perceived rather than on physical numerosity, suggesting that it operates at a level where stimuli are segmented into perceptual units [26].

Overall, these findings suggest that although priors may distort perceptual representations, they likely originate from high-level processing stages, at the level of abstract information processing and judgment. Serial dependence may arise at high levels of the visual hierarchy while still affecting lower levels, producing a perceptual bias that alters stimulus appearance rather than memory or judgment [20, 27]. Within this framework, high-level areas may modulate lower-level regions via top-down signals. Priors may originate in the parietal cortex, which is known to encode numerical representations regardless of stimulus format (simultaneous vs. sequential [69]) and to be sensitive to attentional modulation [70, 71], both key characteristics of serial dependence effects. This aligns with previous fMRI studies showing that another history effect, adaptation, can alter both the pattern of activity elicited by numerosity and the preferred numerosity within the numerosity maps in the parietal cortex [72, 73]. These high-level areas may then propagate top-down signals to influence earlier stages of visual processing. This interpretation is supported by evidence showing that signatures of serial dependence during numerosity tasks can be read out from early VEPs, and with the observation that backward masking—known to disrupt top-down signals—suppresses the effect [20, 22, 26, 68].

These considerations can also be applied to other domains of perception, such as orientation. A seminal fMRI study by John-Saaltink and colleagues [74] demonstrated that, in the context of orientation perception, the previous stimulus modulates neural representations in V1. Building on the surround tilt illusion, Cicchini and colleagues [75] disentangled the site of generation from the site of action of priors. They found that serial dependence was strongest for a neutral stimulus preceded by an illusory one when the perceived orientations matched, suggesting that priors are high-level constructs that incorporate the effect of the illusion. Conversely, when an illusory stimulus was preceded by a neutral one, serial dependence was strongest when their physical orientations matched, indicating that priors act on early sensory input before it is biased by flanking stimuli. More broadly, these findings align with predictive coding models, which propose that priors are generated at higher processing levels and subsequently fed back to earlier stages, where they are tested against sensory input [76].

Beyond the theoretical and neural considerations discussed above, a further aim of our study was to investigate any potential influence of additional factors (e.g., arousal) captured by the MA questionnaire on determining history effects. To this end, we correlated history effects with MA while controlling for sensory precision. Given that individuals with HMA may experience increased arousal during math-related tasks, and arousal affects perception and decision-making [77], this factor warrants consideration. In the current study, controlling for sensory precision strongly decreased MA’s predictive power, though a trend remained for central tendency. These findings suggest that sensory precision accounts for most of the variability. Nonetheless, future research should explore whether MA (and arousal), possibly measured through more refined psychophysiological indices, can predict history effects over and above sensory precision.

Another limitation of our design concerns the numerosity range used in the task. Responses to small numerosities are typically highly accurate, which can mask the strength of history effects. In our analyses, the central tendency bias was mainly driven by the underestimation of stimuli above the average numerosity, while responses to low numerosities remained near veridical. This pattern may have limited our ability to fully capture central tendency biases in participants with HMA. Therefore, future studies employing a higher numerosity range may be necessary to better assess how central tendency varies with math anxiety.

A final goal of the study was to clarify whether central tendency and serial dependence reflect a single mechanism or represent independent processes. Although current perception can be shaped by both the distribution range and the immediately preceding stimulus, most studies typically focus on one of these two phenomena. Only a few researchers have attempted to relate these two history effects. For instance, Tong and Dubé [51] proposed a unified model, validated through three estimation experiments focusing on line length and spatial frequency. According to their model, responses to a given stimulus depend on a fidelity-based weighted sum of two memory representations [51]: the probability density distribution of the current stimulus and a Gaussian mixture model of previous stimuli. In this model, more recent items, characterized by higher fidelity, are given greater weight. This fidelity-driven integration of memory traces is proposed to underlie both central tendency and serial dependence effects [51].

Conversely, Saarela et al. [6] analyzed participants’ responses in color and line length tasks using a GLMM with serial dependence and central tendency as predictors. They found that both phenomena contributed significantly and independently, supporting the idea that these two history effects are distinct. Further evidence for their independence comes from correlational studies, which have found no significant association between central tendency and serial dependence in numerosity [9] and body size perception [33]. While the relationship between central tendency and serial dependence effects warrants further investigation, our results are in line with these latter studies showing no significant correlation between these two phenomena, suggesting that they may tap into separate or at least partly independent mechanisms.