By Stuart Mitchner

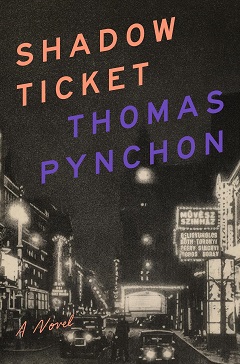

Writing about Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day in January 2007, I chided reviewers for warning readers away from the almost 1,100-page-long novel as if it were “a brilliant but perilous ruin.” In September 2009, I took issue with reviews describing Pynchon’s Inherent Vice as “a beach read,” a “page-turner,” a “breezy work of genre fiction,” an “amusing snapshot.” Calling it a convoluted jeu de cannibas, less a page-turner than a mind-twister, I said that just as marijuana can make a minute feel like an hour, Pynchon can make his novel’s 369 pages feel like 800. Of his last book, Bleeding Edge, which surfaced 12 years ago: “You’re on Planet Pynchon, love it or leave it. But if you leave it, you miss some of the best writing about New York City since Henry James’s American Scene.” In his new novel Shadow Ticket (Penguin $30), 293 pages feels like 293 pages. To extract a bigger, more satisfyingly Pynchonesque book you have to do some digging.

Writing about Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day in January 2007, I chided reviewers for warning readers away from the almost 1,100-page-long novel as if it were “a brilliant but perilous ruin.” In September 2009, I took issue with reviews describing Pynchon’s Inherent Vice as “a beach read,” a “page-turner,” a “breezy work of genre fiction,” an “amusing snapshot.” Calling it a convoluted jeu de cannibas, less a page-turner than a mind-twister, I said that just as marijuana can make a minute feel like an hour, Pynchon can make his novel’s 369 pages feel like 800. Of his last book, Bleeding Edge, which surfaced 12 years ago: “You’re on Planet Pynchon, love it or leave it. But if you leave it, you miss some of the best writing about New York City since Henry James’s American Scene.” In his new novel Shadow Ticket (Penguin $30), 293 pages feels like 293 pages. To extract a bigger, more satisfyingly Pynchonesque book you have to do some digging.

“The Big Cheese”

Imagine an R. Crumb cartoon of a beady-eyed rodent, teeth bared, staring out of a mouse hole at an invisible trap baited with a gigantic piece of Wisconsin cheddar radiant as a Lake Michigan sunrise. Thus The New York Review of Books bites and ducks, with a long, relatively insightful piece headed “The Big Cheese” above a mug-shot-style graphic based on the author’s senior high school yearbook photo. And, as most reviewers have noted while licking the cheddar from their chops, Shadow Ticket may be the 88-year-old’s last shot: for this reviewer, the swansong of a great American writer.

Out of Context

While the novel contains nothing like a formal farewell, one of the closing chapters is haunted by the hint of one in an exchange between the gumshoe hero Hicks McTaggart and the errant heiress Daphne Airmont, daughter of Bruno, the Al Capone of Cheese. This is the fall of 1932 in Budapest. For Hicks imagine Clark Gable in It Happened One Night (1934) after breaking up runaway heiress Claudette Colbert’s marriage. The passage in question begins, “What one of them should have been saying was ‘We’re in the last minutes of a break that will seem so wonderful and peaceful and carefree. If anybody’s around to remember. Still trying to keep on with it before it gets too dark. Until finally we turn to look back the way we came, and there’s that last light bulb, once so bright, now feebly flickering, about to burn out, and it’s well past time to be saying [in case the reader begins to take the tone too seriously], ‘Florsheims, let’s ambulate.’”

Next paragraph: “Stay or go. Two fates beginning to diverge — back to the U.S. marry, raise a family, assemble a life you can persuade yourself is free from fear, as meanwhile, over here, the other outcome continues to unfold, to roll in dark as the end of time. Those you could have saved, could have shifted at least somehow onto a safer stretch of track, are one by one robbed, beaten, killed, seized and taken away into the nameless, the unrecoverable.

“Until one night, too late, you wake into an understanding of what you should have been doing with your life all along.” Then: “Something like that. If anybody was still there to hear it. Which there isn’t.”

Cheese or Cinema

Pynchon has fun riffing on cheese as he builds his story (one of his best is the play on Edward G. Robinson’s dying words in 1931’s Little Caesar), which moves from Milwaukee to Budapest and Fiume (not all that far from the Maltese setting of V, his first novel). Employed by Unamalgamated Ops, Hicks has a “shadow ticket” instructing him to find and bring home Daphne, who has run off with Hop Wingdale, a clarinet player for a band called the Klezmopolitans.

Although I dutifully followed the cheese plot all the way, my interest was actually initially engaged by the circa 1930s photograph, which shows the Művész Színház (Art Theater) on Nagymező utca in Pest, which has since become a nightclub, according to a post on Reddit. It’s also worth noting that the book’s epigraph is courtesy of Bela Lugosi in The Black Cat (1934): “Supernatural, perhaps. Baloney . . . perhaps not.” In an early chapter, Hicks takes his girlfriend April to Lugosi in Dracula, which opened in Chicago on Valentine’s Day, as Pynchon makes sure to tell us. By the time the film was over, April had eaten “six cubic feet of popcorn” and was using his tie “to wipe the butter off her fingers.” She’s knocked out by Lugosi (“some kind of Hungarian oomph there”). Hicks imagines her whispering Bela’s name in her sleep.

Enter Diane Keaton

In case Lugosi’s reference to “supernatural” seems a stretch, you can be in the middle of another screwball love scene in 1930s Milwaukee when you’re told of Diane Keaton’s death in October 2025, delivered while Hicks and April are dancing (he’s a pro) and she’s calling him “you big chump” and crying “all over his shirt just back from the Chinese place.” The fact that one of Keaton’s most memorable roles is as Michael Corleone’s wife in The Godfather fits nicely with April Randazzo, who is “all but the kept tomato of Don Peppino Interfernacci.”

Meanwhile Hicks is crooning a Pynchon love song into April’s ear as they dance: “you’re ubiquitous . . . like the airwaves through the air . . . how ridiculous-ly I’m yearning, into what a sap I’m turning….” And no wonder as she’s showing off “the sparkler”on her finger in case he doubts that Don Peppino is a Calbrese “who’d rather kill you than work things out.” By this time, however, April is taking on shades of the Wisconsin girl Keaton played in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. When Hicks keeps making light of the threat, April turns her face away and chides him for “the happy patter, you Einsteins, what is it with you? heads in the fog, never know how much trouble you’re in.”

As it turns out, my reading of supernaturally ubiquitous Hollywood in Pynchon’s vision of early 1930’s Milwaukee (“like nose tissue at a Garbo movie”) makes an easy 80-year leap to mid-October 2025 viewings of Diane Keaton in her glory in Annie Hall (1977), a joy wowing and wowed by Jack Nicholson in Something’s Gotta Give (2003), and going movingly face to face with Meryl Streep in Marvin’s Room (1996).

Dracula in Milwaukee

No cheese for me. As long as Pynchon’s providing prose like the Lugosi-inflected opening of Chapter 11, where “on days of low winter light” the federal courthouse in Milwaukee “can take on a sinister look, a setting for a story best not told at bedtime, the jagged profile of an evil castle against a pale light reflected off the Lake, bell tower, archways, gargoyles, haunted shadows, Halloween all year long. Or as some like to think of it, Richardsonian Romanesque. Heavy icicles all along the overhangs, waiting to let loose and pierce your skull….”

A Metaphysical Critter

References to the motorcycle as “a metaphysical critter,” “more tall tales from the wild highways,” and “there’s a fierce living soul here that we have to deal with” remind me to mention Pynchon’s old friend Richard Fariña (1937-1966), to whom he dedicated Gravity’s Rainbow.

Written by: Stuart Mitchner