“If I abandoned this project, I would be a man without dreams and I don’t want to live like that.” Werner Herzog sits on a hammock in a hut deep in the Amazon. Rain lashes down outside, thunder rolls in the distance. The German filmmaker hasn’t shaved in days; he looks knackered. But his eyes are alight with purpose. “I live my life or I end my life with this project,” he says.

The year is 1981, and Herzog, then in his late thirties, is shooting Fitzcarraldo, an epic about a manic dreamer who hauls a steamship over a mountain in search of rubber, in the hope of making enough money to build a glorious opera house in the rainforest. The filming of Fitzcarraldo, chronicled in Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams, was more dramatic than most Oscar-winning dramas. Herzog insisted on shooting in the Amazon, where the starry cast slept in humid tents, fought off snakes, and dodged poisoned arrows hurled at them by disgruntled locals. He also refused to use special effects and insisted on actually pulling a steamship over a mountain — a feat which required months of gruelling engineering, and the help of Amazonian tribes.

Few directors have ever gone so far in pursuit of a vision and come out with a cinematic masterpiece. Directing Fitzcarraldo, Herzog gazed into the abyss, but the abyss didn’t dare gaze back at him. His dream was too magnificent, too irresistible. It had to be woven into the fabric of reality.

Since then, Herzog has realised many more dreams. He’s directed feature films, documentaries and even operas; he’s written poetry, essays and a novel. In the process, Herzog, now 83, has become a pop-culture icon, acclaimed for his lyricism and erudition — as well as his hypnotic voice and thick Bavarian accent. Like his countryman Friedrich Nietzsche, he has a knack for coining aphorisms (a favourite: “Civilisation is like a thin layer of ice upon a deep ocean of chaos and darkness”). In an era of shallow influencers, he has struck a chord with audiences hungering for meaning.

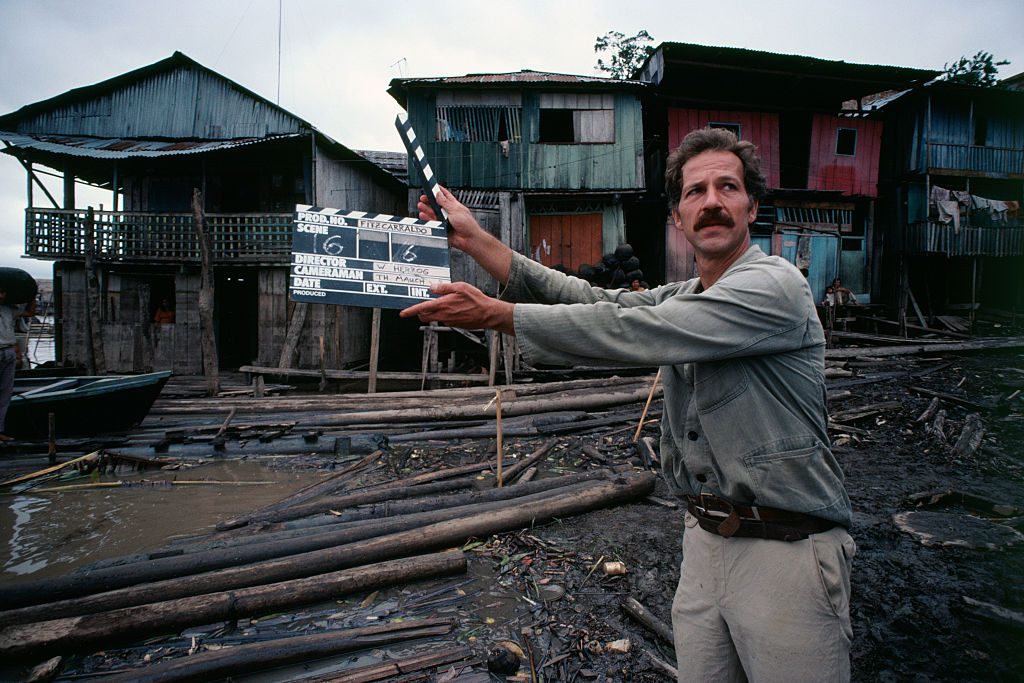

Herzog on the set of Fitzcarraldo in Peru. Jean-Louis Atlan/Sygma/Getty Images

Herzog on the set of Fitzcarraldo in Peru. Jean-Louis Atlan/Sygma/Getty Images

Now comes a new book grandly titled The Future of Truth. Think of it as DMT in hardback. Beautifully translated from German by Michael Hofmann, it’s a collage of reflections, visions and stories about what constitutes truth.

Look up the definition of “truth” and you’ll learn it is “conformity with fact”. But this doesn’t impress Herzog. “It’s a definition of a complete dimwit,” he tells me when I ask him over Zoom. The director is sitting in his study in Los Angeles, looking down at the camera. “If facts constituted truth, it would be fairly simple, but it is not,” he continues. “We would have the accountant’s truth, and not something much deeper.”

Herzog tells me there exists no scholarly consensus on what truth really is. “It may be related to facts to some degree. But at the same time, the question arises: what are facts? And what is reality?” he says. “Reality is hotly disputed as well. What is the reality of the man in the lunatic asylum who believes he is Napoleon Bonaparte or Lenin or Jesus Christ?”

For Herzog, it doesn’t matter that we have no definitive definition of truth. “It is within the human condition that we know that we are in search of truth,” he says. “We know vaguely where it is, vaguely a direction, and all the rest is nothing but search, an expedition into the unknown, a quest, an endeavour never ending.”

“It is within the human condition that we know that we are in search of truth.”

It’s an endeavour that has animated Herzog since he first picked up a camera as a teenager. From the glaciers of Antarctica to the dunes of the Sahara, he’s been on a personal expedition for what he calls “ecstatic truth” — truth beyond facts.

“I’m speaking now purely of art,” Herzog warns, making clear that if you are in the business of political journalism, “you better do fact checks and you better not mislead your audience”. But for artists, he continues, “departing from the clear, understandable, natural facts can enhance the truth of something”.

Herzog gives the example of Michelangelo’s Pietà, a sculpture in St Peter’s Basilica which depicts Jesus in the arms of Mary after he was taken down from the cross. “His face is correctly the face of a 33-year-old man,” Herzog explains, “but when you look into the face of his mother, the mother of a 33-year-old man is probably only 15. So I immediately asked myself the question: did Michelangelo try to give us fake news, did he try to cheat us?” Yet the opposite is true. “He gives us a deeper truth, something deeper about the essence of the two figures.”

In a nutshell, that’s Herzog’s approach too. Take his 2001 film Invincible, set in Berlin at the outset of Nazism, which follows the tribulations of Zishe Breitbart, a Jewish strongman who performs nightly in a cabaret. The cabaret’s owner, Erik Jan Hanussen, is a clairvoyant who dreams of becoming Hitler’s Minister of the Occult. Given the rampant antisemitism, Breitbart cannot perform under his own name, since Jews are supposed to be weaklings. Hanussen therefore makes him play the part of a Germanic folk hero — until Breitbart resolves to reveal his true identity.

Though Breitbart and Hanussen were real historical figures, their paths never actually crossed. Breitbart died in 1925, nearly a decade before Hitler gained power. Herzog sculpted a fictional story around their real lives. “Who cares that I invented a meeting that could have not taken place?” he says. “It doesn’t matter. I am a poet, period.”

In Invincible, poetic licence illuminates a reality that eludes facts. The film illustrates the sinister spell Nazism cast on Germany and how it affected Jews. Herzog, who was born during the Second World War and is part of the generation of Germans that had to confront the Nazi past, said of the film: “That’s my answer to the darkest history of Germany.” It’s an answer that doesn’t replace the study of history but completes it.

Watch any Herzog film, and you’ll see the same process at play. Many of them are inspired by true stories, but Herzog sublimates those stories to reveal their essence. Just don’t ask him to explain what that essence is. He once referred to Fitzcarraldo as “a big metaphor”, adding, “but don’t ask me what the metaphor means, because I wouldn’t know”.

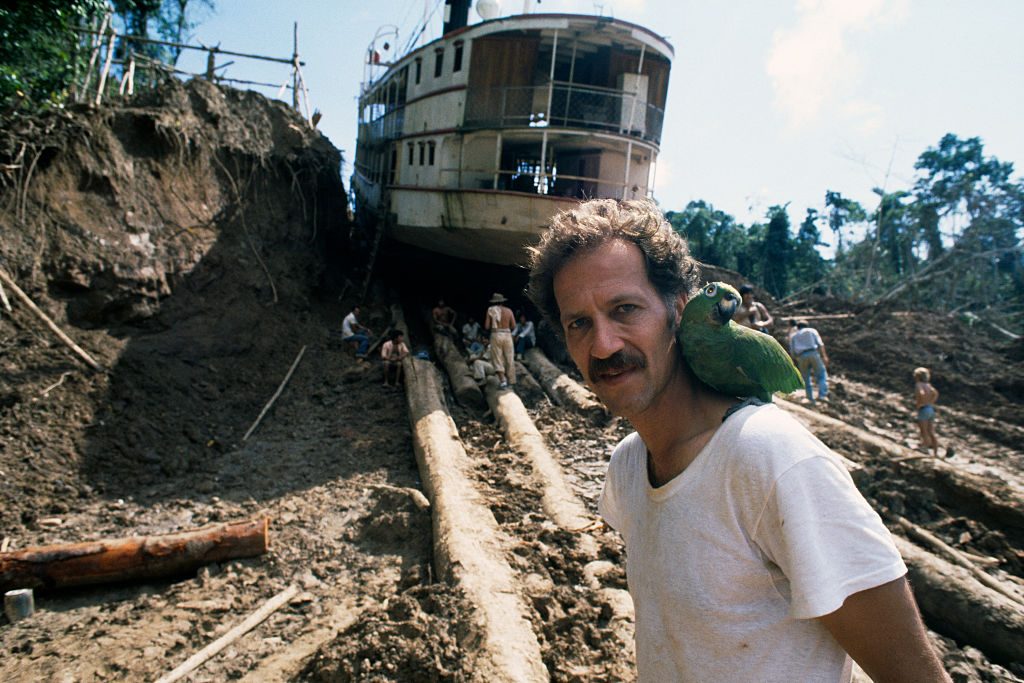

‘Directing Fitzcarraldo, Herzog gazed into the abyss, but the abyss didn’t dare gaze back at him.’ Jean-Louis Atlan/Sygma/Getty Images

‘Directing Fitzcarraldo, Herzog gazed into the abyss, but the abyss didn’t dare gaze back at him.’ Jean-Louis Atlan/Sygma/Getty Images

Even before he picked up a camera, Herzog was chasing the ineffable. At the age of 13, growing up in the Bavarian Alps, Herzog was briefly a devout Catholic. “There was a deep void in me and a longing for something transcendent, so that was probably the deeper reason behind all this,” he tells me. He then leaps elegantly from his youthful flirtation with Catholicism to his search today for “ecstatic truth”. “Ekstasis in Greek means to stay out, to step outside of yourself,” he tells me. “You see that in late medieval mystics and the kind of insight they have on the nature of faith by stepping outside of their existence.”

Herzog likens this experience to that of ski jumpers. In 1975, he released The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, a documentary about Walter Steiner, a Swiss sculptor and ski-jumping champion. “[Steiner] defies gravity and flies off ramps, and he has the experience of ecstasy, stepping out of his existence and morphing into a bird,” Herzog tells me. “And it’s strange,” he continues, “because I wanted to be an athlete when I was very young, I wanted to become world champion of ski flyers.” He quit after his best friend had a “catastrophic accident”. But “even if I had continued”, he adds, “I wouldn’t have gotten even close to what [the greatest ski jumpers] are capable to do”.

But Herzog’s youthful desire to be an extreme athlete helps to explain his radical approach to filmmaking. For Herzog is to cinema what Steiner was to sport. When Steiner jumped off a ski ramp into the void, he hadn’t lost his mind. He knew exactly what he was capable of. What appears insane to us appeared possible to him. And it was possible. Ditto with Herzog. His career is a masterclass in how to discipline the mind’s eye. He’s a practical visionary; a poet with the discipline of an engineer.

Herzog has long gravitated towards characters who, like him, reject limits, from scientists working in Antarctica to cops who flaunt the law in New Orleans. Then there’s Elon Musk, whom Herzog interviewed in his 2016 documentary about the internet, Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World.

“Elon Musk, I think, he’s not one of these imposters,” he says, when I bring up the Tesla and SpaceX CEO. “He’s a serious businessman, but he knows about the power of myth… This is why he keeps insisting on colonising Mars with a million human beings.”

“Elon Musk, he’s not one of these imposters.”

Herzog doesn’t share Musk’s enthusiasm for the red planet. “Speaking about colonising Mars with a million is an obscenity by itself, because we should keep our own planet habitable and not try to make a hostile planet habitable for us,” he says. “So there’s something wrong about it… and it is not attainable. It cannot be reached.”

He’s clearly given the project some thought, however. We’d need “to fire salvos of rockets, thousands of them almost at the same time”; we’d need to build “robots who construct huge domes”; we’d need to detonate “atomic explosions at the poles of Mars for melting water”. And if that wasn’t enough, we’d need to build pipelines to transport the water. “Now, please, how do you construct the pipelines?” Herzog asks. “It is ridiculous. We know that. You don’t need to be a chicken to know the egg is rotten. You don’t need to be an astrophysicist to know that.” If the man who pulled a steamship over a mountain calls for time-out, you know you’re in trouble.

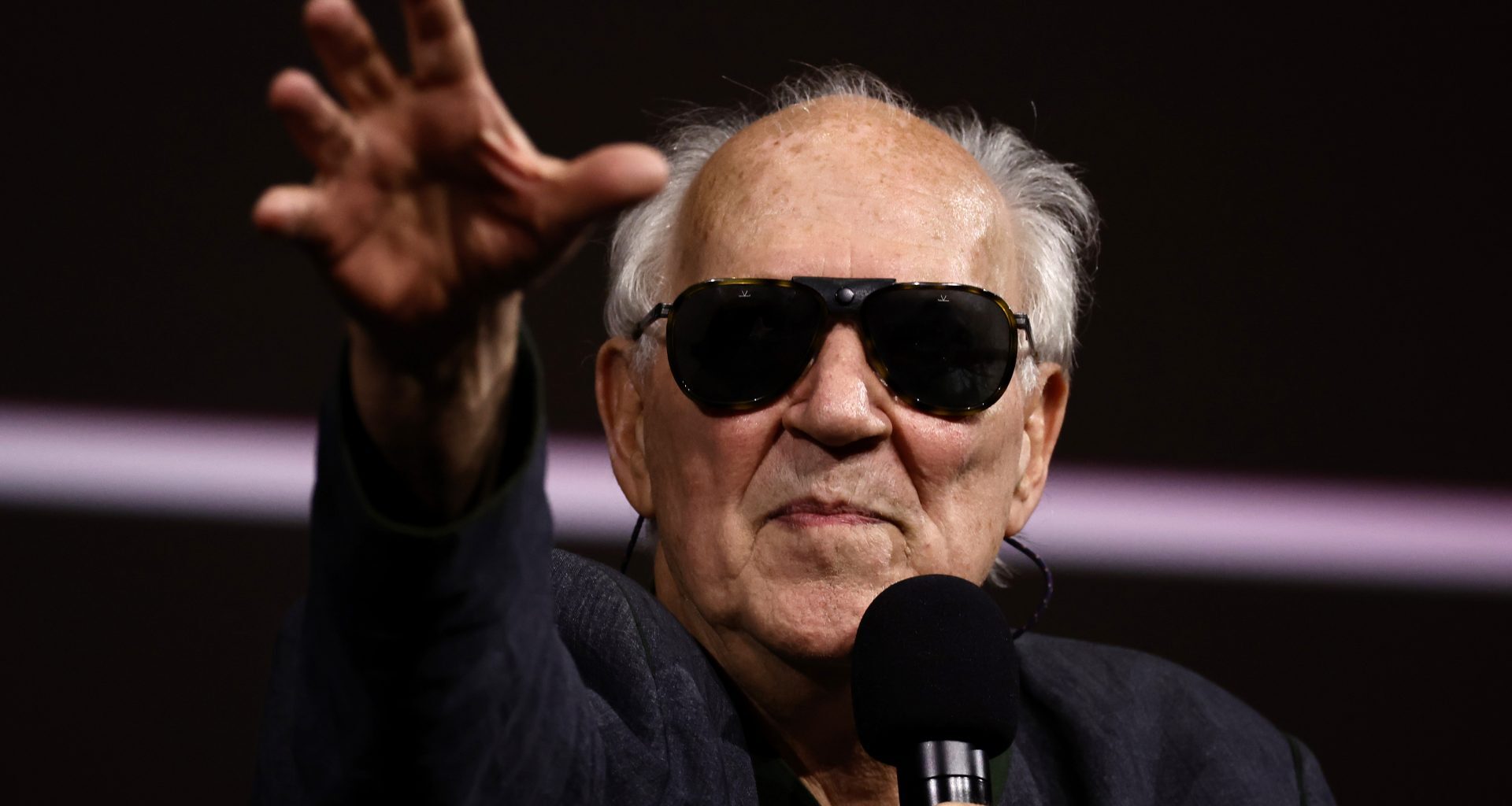

Herzog at this year’s Venice Film Festival. Ernesto Ruscio/Getty Images

Herzog at this year’s Venice Film Festival. Ernesto Ruscio/Getty Images

But Musk’s Martian hype is cunning PR. “He acquires the aura of the visionary. That’s important,” Herzog says, “because when you buy an electric car, you do not buy it from the Chinese because it’s just a factory in China. If you buy one of his cars, you buy the car of the visionary. It’s an attribute that goes into mythologising the product. I’m sure he’s aware of that. He’s not a stupid man.”

Musk also dreams of creating a new life form: artificial intelligence. It’s a prospect that unnerves Herzog. In The Future of Truth, Herzog acknowledges that AI will lead to extraordinary breakthroughs, but also foresees “the possibility of comprehensive, mass supervision of disinformation, of manipulation on a vast scale”. This echoes the haunting epilogue of his memoir, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, in which he imagines a world “turning away from thought, argument, and image… a darkness filled with fear, with imaginary monsters”.

In this dark new world, nobody will read. Herzog has long warned that the decline in reading spelt doom for humanity. New studies highlight how serious it is: reading for pleasure has collapsed, and even elite university students now struggle with long texts. “Students read less and less and less, and young filmmakers do not read at all,” he tells me. “I keep telling them, I keep hammering into them: if you want to become a filmmaker, you may become a mediocre filmmaker at best, but you will only become a good filmmaker if you read.”

“Read, read, read, read, read,” Herzog says, like a mantra. “That’s of fundamental importance for our future.” Only by reading widely can we develop critical thinking. “Your mind engages with the soul in the thinking of someone else, and then you read another book, and you have another worldview, and all of a sudden you start to balance it out… and see our daily reality in critical terms,” he says.

In The Future of Truth, Herzog calls on us to discern fake news by consulting a plethora of sources. Don’t take anything on blind faith. Only then can we hope to build a “more nuanced version of what reality might be”.

“It has to become second nature for us the same way it was apparently second nature for prehistoric men, hunters and gatherers,” Herzog continues in a flight of poetry. “They would go out and pick berries and mushrooms, and I’m certain they did not pick the poisonous ones. Over long, long experience, they would know. And I keep saying: I’m fairly certain that these people did not hate nature because there was poison in it… It’s the same thing today. You do not have to hate the world as it is. You just have to get acquainted with doubt and critical thinking.”

The search for truth, as Herzog tells us in his book, is eternal. Our ancestors looked for it on the walls of prehistoric caves; we can’t now forsake it for the shiny screens of our smartphones. “Truth has no future, but truth did not have a past either,” Herzog tells me. “But we must pursue it. We have to continue, we must, we shall continue to search for it.”

***

The Future of Truth by Werner Herzog, translated by Michael Hofmann, is published by Bodley Head.