Johannes Vermeer is the artist who vanished. We know that he was baptised in Delft in 1632 and died there in 1675 at the age of 43. We know that he was admitted to the painters’ guild in 1653 and married the same year. He fathered 15 children, four of whom died in infancy. He dealt a little in pictures, served in the city militia, and left debts for his widow to pay. He appears in a ledger here, a register there. He is mentioned — briefly — in the diaries of two visitors to Delft.

But there are no letters, no journals, no sketchbooks, no loose-leaf drawings, no treatise — not one written word. He left to posterity only — only! — his paintings: 34 (or 35 or 36 or 37, depending on fashions in attribution) extraordinary, elusive pictures that have captivated gallery visitors and confounded scholars. The French art critic and connoisseur Théophile Thoré called Vermeer “the Sphinx of Delft.” The faint traces and missing pieces have lent themselves to fiction. Tracy Chevalier’s novel Girl With a Pearl Earring has sold more than five million copies.

• Fake Vermeers that conned the Nazis get their own exhibitions

Within a generation of his death, Vermeer had been forgotten. His works were passed off as those of more sellable masters: Pieter de Hooch, Frans van Mieris, Rembrandt van Rijn. He was, as Andrew Graham-Dixon writes in the introduction to his riveting new biography of Vermeer, a “nobody.”

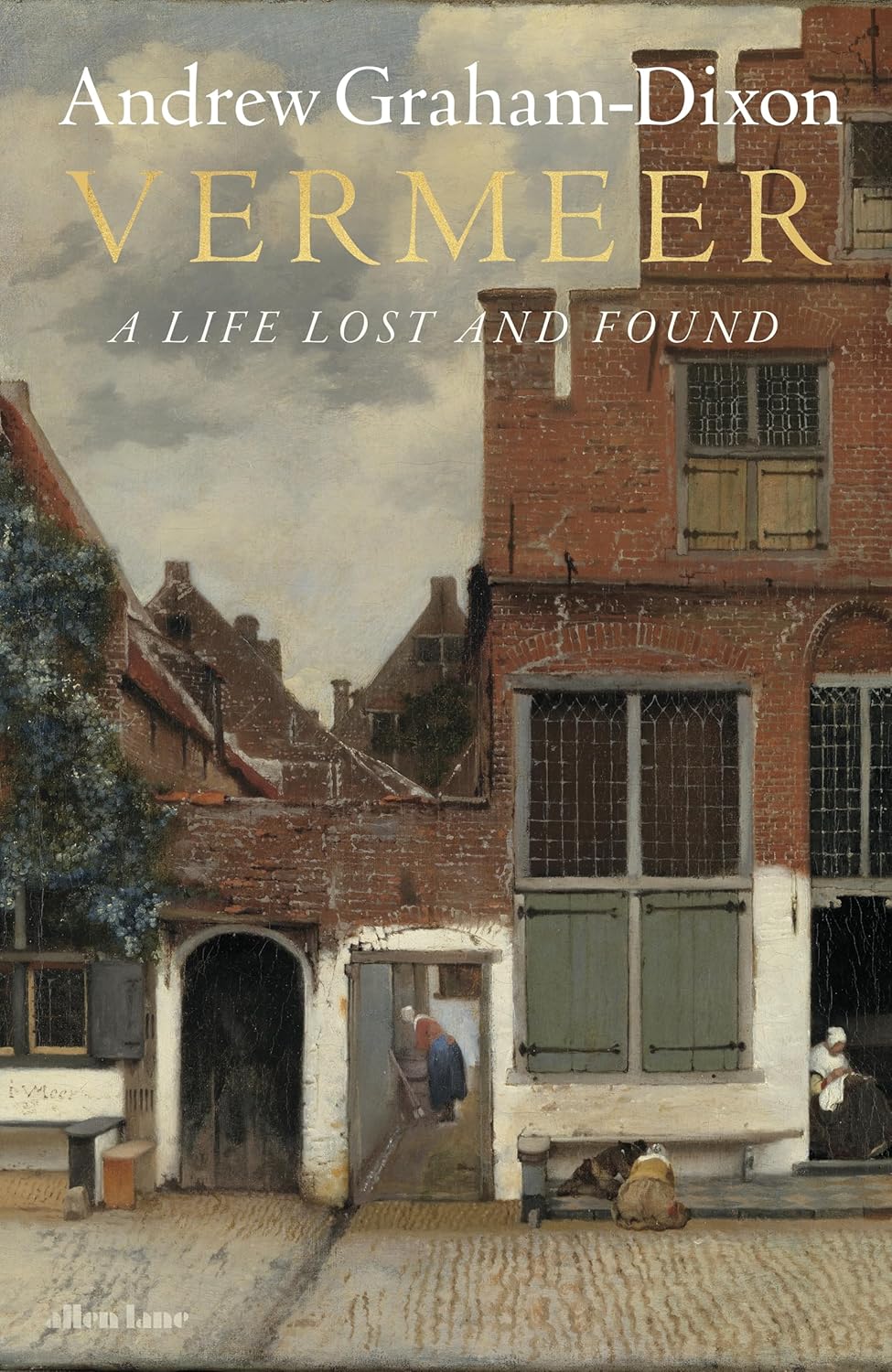

This isn’t a tell-all life. Graham-Dixon hasn’t unearthed love children or secret confessions or crimes of passion. Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found is instead a powerfully persuasive investigation into the intellectual and devotional world of Vermeer and his circle. Painting by painting, the riddle of the Sphinx is masterfully unravelled.

It takes time to get going. Graham-Dixon rightly argues that we cannot understand Vermeer without understanding what came before. I confess that I found the “inheritance” chapters — the Eighty Years War for Dutch Independence, the still more bloody Thirty Years War — hard work. Siege on siege, massacre on massacre, atrocity after atrocity, stronghold and surrender; schism and council, synod and sect. As one Reformed minister in Delft put it: “This Dutch land is as full of religious sects as the summer is full of mosquitoes.”

You have to understand the dark century and the many dissenting beliefs and practices it created if you are to understand “Johannes Vermeer, future painter of peaceful rooms flooded with light”. When we get to Vermeer proper, it is as if Graham-Dixon has thrown open the casement window and let the low, strong Delft winter light pour into the book.

• Forget Vermeer — the Golden Age master Frans Hals got the last laugh

His reading of the paintings is revelatory. He trawls the archives, lays out new evidence, links pictures never linked before, and teases new meaning from signs, symbols and sitters. Graham-Dixon was for many years the art critic of The Sunday Telegraph and is a veteran arts broadcaster for the BBC. He knows the value of the scoop, of pace, of “tune in after the chapter break”. Forget The Da Vinci Code, the Vermeer Code is infinitely more intricate. Where Dan Brown heaps improbability on implausibility, Graham-Dixon convincingly follows trails, decodes clues and holds you in suspense for the big reveal.

His argument springs from one crucial under-considered fact about Vermeer’s body of work: 20 of Vermeer’s paintings were painted for just one couple, Pieter Claesz van Ruijven, the heir to a brewing fortune, and his wife, Maria de Knuijt, a woman of independent means and radically independent thought.

The Van Ruijvens were Collegiants. (Pay attention to all those sects at the start.) The Collegiants were free-thinking, pacifist and tolerant. They believed in equality of the sexes and open discussion of the Bible. They met privately in each other’s houses. A quiet room — the sort of room Vermeer painted — served as a church.

• Brain scans reveal appeal of the Girl with a Pearl Earring

Graham-Dixon makes the case that Vermeer’s pictures for the Van Ruijvens weren’t secular “genre” pictures — scenes of daily Dutch Golden Age life — as painted by his contemporaries, but a complex iconographic program which expressed their faith, aided their devotions and drew others into their worship.

Although Vermeer converted to Catholicism on his marriage to Catharina Bolnes — her mother Maria Thins was a Catholic and it was she who ran the household and held the purse strings — his true beliefs may have been closer to those of the Collegiants.

Graham-Dixon writes beautifully of the outward appearance of the paintings — the sheer brilliance of technique and grace in arrangement — and their inner meaning. The roofs of a View of Delft glitter wet in the aftermath of a storm both sacred and temporal. The flour-dusted bread on the table in The Milkmaid is rustic yet miraculous.

He believes — and I believe him — he has found the real life location of The Little Street. It was painted for the Van Ruijvens and would have hung in the house with the black door that we see to the left of the painting. Vermeer even signed his name in the house’s plaster.

• Mystery of the ‘fake’ Vermeer has experts splitting hairs

Graham-Dixon argues that The Milkmaid and Woman Holding a Balance, which were hung in different rooms in the Rijksmuseum’s blockbuster Vermeer exhibition in 2022, were, in fact, conceived as a pair and intended to be read as exemplars of the active (Milkmaid) and contemplative (Woman Holding a Balance) life and as counterparts of the New Testament story of Martha and Mary. The book’s colour plates sit them side by side, illuminating their rhymes and responses in composition and colour. Vermeer’s The Astronomer and The Geographer are also read as pendants, full of symbols and rebuses that illustrate their messages about heavenly and earthly realms.

Girl with a Pearl Earring, c1665

ALAMY

And what of Girl with a Pearl Earring? That most Sphinxish of paintings by this most Sphinxish of painters? The identity of the beautiful, inscrutable girl in her turban has eluded us for centuries. Graham-Dixon may have caught her. The Van Ruijvens had a daughter: Magdalena. She would have been about 12 when Girl with a Pearl Earring was painted. It may have been painted to mark her baptism. But she isn’t dressed as Magdalena, a girl of the 17th century. Her costume is “all’antica”. Magdalena has become Mary Magdalene — and at a very particular moment. She is neither facing us nor in true profile, but captured in the act of turning as Mary Magdalene does at the empty tomb of Christ when she hears the voice of the gardener behind her.

If Graham-Dixon is right, then Christ has not only risen but is resurrected right beside us. He writes: “The pearl at her ear is impossibly large because it is no simple jewel but a reflection of the state of her soul, bursting with joy and irradiated with divine light.” There go the hairs on the back of my neck.

• Pictures of vicious 1968 attack on Vermeer painting revealed

Occasionally, Graham-Dixon overeggs it. He lost me when it came to The Lacemaker. If the sewing cushion with its spilling red threads represents a woman’s womb, her veins and arteries pulsing with blood, then I’m a Dutchman.

No matter. You don’t have to believe every word to be a true believer. This is a fascinating portrait of Vermeer, his times and his mind. The reading and reframing of the paintings will hold you rapt. You’ll never look at a Vermeer in the same way again.

Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found by Andrew Graham Dixon (Allen Lane £30 pp416). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members.