More commercial activities are taking place in the global ocean than ever before. But companies’ effects on marine ecosystems are worryingly opaque, say experts who have examined the biggest ocean businesses.

The marine environment is essential to modern economies. Companies are exploring deep-sea mining in the Pacific, fishing for krill off Antarctica, and drilling for oil and shipping cargo across all five major oceans.

“The diversity and the intensity of today’s activities are unprecedented, and that confronts us with the big question: how do we make sure we do that right?” asks Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, a researcher at Stanford University’s Center for Ocean Solutions in the US.

His starting point for finding an answer was to look at 80 of the largest companies working in the ocean and see how they reported on everything from energy utilisation to pollution and fishing between 2018 and 2020.

Jouffray and his colleagues wanted to understand what companies were disclosing to the public and their investors, and how their activities impact the ocean and the life within it. Their findings were published last month in the journal Nature Sustainability.

“We wanted to see: are they reporting their impact? Are they measuring their impact? Are they setting goals and targets for their impact? And the short answer is: no, they are not,” he tells Dialogue Earth.

Big businesses, big impacts

The list of companies Jouffray’s team analysed includes: the shipping firms COSCO and Maersk, which sail massive containers vast distances every day; the cruise companies Royal Caribbean Cruises and Hurtigruten, which carry thousands of tourists across oceans; and the oil and gas giants ExxonMobil, Equinor and Saudi Aramco.

Recommended

They looked at annual reports and sustainability reports from these companies and listed the impact “indicators” they found there, such as oil spill counts or how many whales a ship might strike.

For some companies – including the shipbuilding firms Huntington Ingalls Industries, China State Shipbuilding Corporation, and Naval Group – they found no indicators at all.

Some companies’ reports yielded multiple indicators. The Norwegian seafood company Mowi ASA’s reports featured 45, including energy use, seabird deaths and escaped fish. The team’s audit of the cruise operator Carnival Corporation produced 27, including wastewater discharges into the sea and the responsible dismantling of ships.

“What was surprising was that those who do report on it use a wide variety of indicators. In total we found 443,” says Jouffray.

Biodiversity gaps

While most companies reported energy utilisations and carbon emissions, biodiversity damage was far less disclosed. The researchers’ database lists 445 different entries under energy utilisation indicators, but only 77 under indicators related to the alteration of habitats and the removal of biomass and non-native species.

“What is striking is that very few companies measure and set targets for their ocean-specific impact, such as noise, collision with fauna or alteration of habitat”, says Jouffray. “For those who are specifically focused on biodiversity measures, not a single indicator was used by more than two companies.”

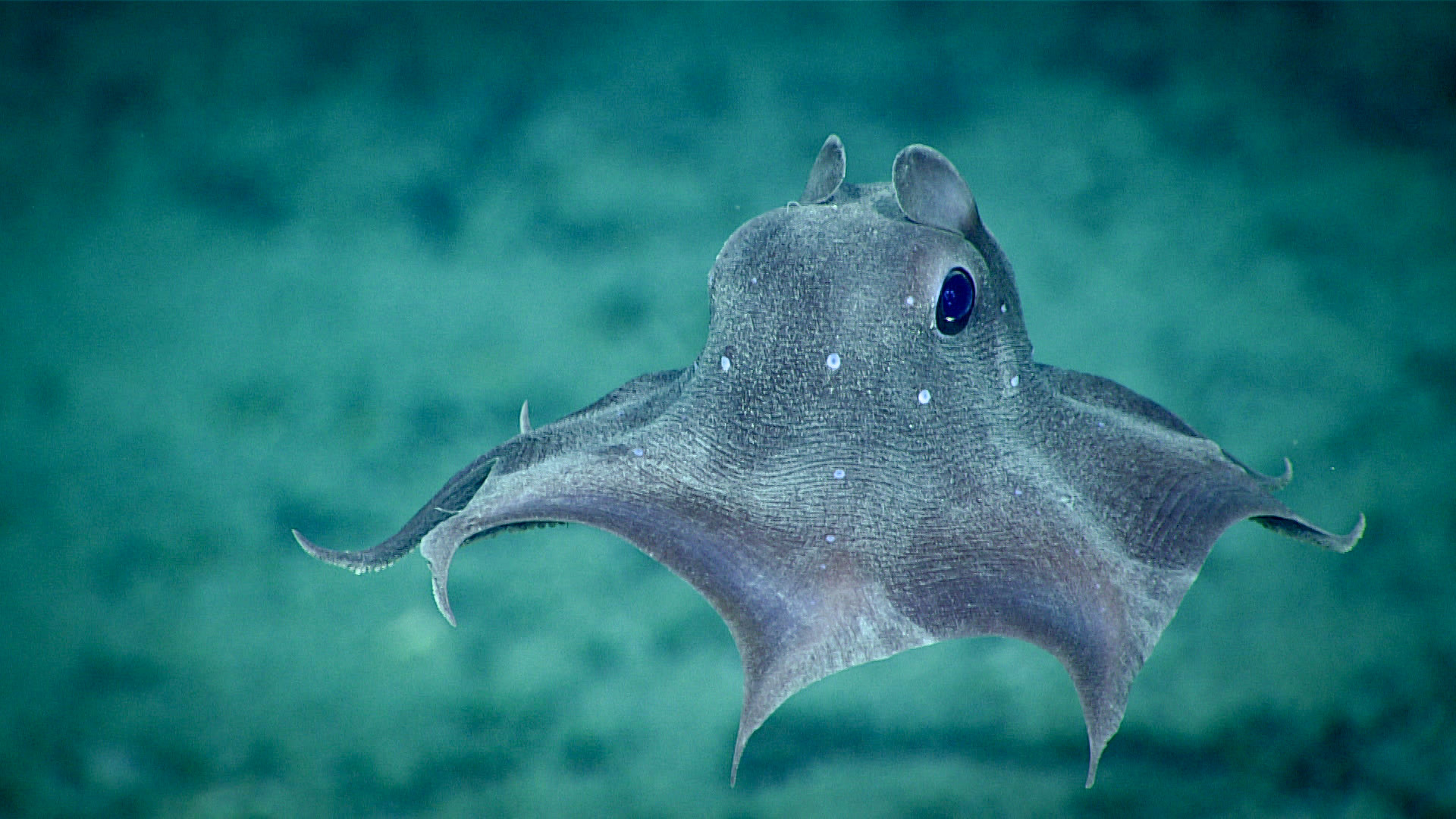

“Dumbo octopus” species like this one propel themselves through the extreme depths using fins on their mantles. Deep-sea mining activities could threaten their existence (Image: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research / Flickr, CC BY-SA)

“Dumbo octopus” species like this one propel themselves through the extreme depths using fins on their mantles. Deep-sea mining activities could threaten their existence (Image: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research / Flickr, CC BY-SA)

The authors emphasise that their study does not judge companies’ actual impact on the ocean, only how those impacts are reported or not reported.

Following the rules

So, why aren’t there more standards and regulations around such reporting?

“Transparency is crucial because without it we don’t have a clue as to what is happening to marine ecosystems and the life they support,” says Rashid Sumaila, an ocean economist at the University of British Columbia in Canada. “This handicaps our ability to manage and ensure a sustainable and regenerative blue economy.”

There are some nascent attempts to bring order to how companies report environmental impacts.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures has ocean-specific components in its disclosure framework. The framework is designed to help companies and financial services to identify, measure and monitor biodiversity risk. Another project, the Global Reporting Initiative, includes reporting on indicators such as biodiversity waste, and water and resource usage.

All these moves fall under the broader term of environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting – a term used to evaluate how companies behave beyond their financial performance.

A 2023 survey of 420 institutional investors working around the world, commissioned by the French bank BNP Paribas, found that 71% worried that “incomplete and inconsistent data” was one of the biggest barriers to greater adoption of ESG. And in recent years, ESG has met with political pushback. Critics argue it is broad, inconsistent and burdensome for companies. In the US, for example, ESG has become highly politically charged, with some states pushing for it, others against.

What are ESG standards?

Companies are increasingly expected to report on their environmental, social and governance impacts. These three areas aim to cover what the professional services network Deloitte defines as: “all the non-financial risks and opportunities inherent to a company’s day to day activities”.

The principle behind ESG is that companies do not exist solely for the generation of profit. Every company is a collection of people who have the potential and responsibility to protect and nourish the environment, prioritise human wellbeing, and govern themselves ethically.

ESG reporting differs from company to company, but the relevant data is typically gathered and added to annual reports or presented as a separate sustainability report.

The European Union had previously stated an intention to roll out its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive between 2024 and 2026. This would require companies to disclose the impact of their activities on people and the environment, though ocean-specific impacts are not separate from terrestrial ones. In 2025, however, parts of the legislation were put on hold, leaving only large companies required to report.

Recommended

“Companies have privacy concerns, which is understandable, but society needs some minimum amount of information to help manage marine habitats and animals in a fashion that is regenerative and truly sustainable,” says Sumaila.

Some nations are plotting a course to clearer reporting. In Japan, sustainability and climate impact disclosures will become mandatory for companies that are listed on the Tokyo stock exchange prime market and have a market capitalisation of at least JPY 3 trillion (USD 19.7 billion), from the end of the 2026-2027 financial year.

France requires the largest companies headquartered there to develop and publish plans addressing human rights, social, health and environmental risks. Singapore is introducing mandatory environmental impact disclosure rules for all Singapore-exchange-listed and large non-listed companies. In 2023, India’s securities and exchange board began asking for supply chain sustainability data from the country’s 250 largest listed companies by market capitalisation.

“Governments, customers and investors are increasingly recognising how biodiversity loss affects businesses,” says Hanne Thornam, head of climate change and sustainability services for EY Nordics, the multinational professional services network. “Regulations that help us reduce this impact will have major implications for the sector going forward.”

There are international targets, too. The UN Sustainable Development Goals require member states to conserve and restore ecosystems, reduce pollution and push for the “sustainable use of marine resources”.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, established in late 2022, also includes language on corporate reporting. However, research published in May suggests much ESG reporting is missing many of the biodiversity issues that the framework is designed to address. And the High Seas Treaty that will come into force in January also requires companies working in international waters to share information on their activities.

Recommended

Without a unified reporting standard for environmental impacts to the ocean, companies may continue to use hundreds of different indicators. Only when impacts are known and understood can action to mitigate them be taken, say experts.

“Reporting is necessary but not a sufficient requirement for ocean companies to operate responsibly. Real responsibility comes from combining hard regulation, economic incentives and community participation to create a robust accountability system for ocean industries,” says Sumaila.

Jouffray adds: “Reporting alone does not solve the problem. It only works if someone applies pressure because of what is reported. For instance, by deciding to increase the interest rate of certain loans or giving penalties for poor environmental performance.

“You can report on as much as you want but ultimately, someone needs to act on that reporting.”

Dialogue Earth has contacted the companies mentioned but none provided comment in time for publication.

\”,\”body\”:\”\”,\”footer\”:\”\”},\”strict\”:{\”header\”:\”\”,\”body\”:\”\”,\”footer\”:\”\”},\”advanced\”:{\”header\”:\”\\r\\n\”,\”body\”:\”\”,\”footer\”:\”\”}}”,”gdpr_scor”:”true”,”wp_lang”:”_en”,”wp_consent_api”:”false”,”gdpr_nonce”:”4067d9cb22″};

/* ]]> */