The interactive nature of short-form video platforms

Launched in 2016, short-form video platforms such as Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok) have enjoyed seemingly unstoppable success. As of June 2022, they had over 962 million users, encompassing 91.5% of Chinese netizens [15]. Two examples of giants in the Chinese short-form video market are Douyin and Kuaishou. Douyin focuses on audiences in first- and second-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, while the target audiences of Kuaishou are citizens of second and third-tier cities and those in rural areas [16]. These mobile-based apps mainly provide video content that is shorter than 5 min.

Although prior social media can also provide short-form videos, current short-form video platforms focus on users’ participation and the replicability of the content production. Three important distinguishing characteristics of short-form video platforms should be noted. First, in terms of design, the “shooting” button is located at the bottom center of the interface, which allows users to start recording a video at any time. This function encourages users to participate in the production process.

Second, compared with other social network sites, short-form video platforms’ communication models center on memes. Specifically, they rely on imitation as social currency rather than chats by offering plentiful, easy-to-use pre-formed templates [17]. These templates typically provide sampled material such as audio and emoji memes; Hashtags can also constitute memes [18]. Users need only pick their preferred template and upload their photos or videos into the template. The apps process the photos or videos and automatically generate and edit a final video. For example, many Chinese users used Bing Dwen Dwen mascot memes during the run-up to the 2022 Winter Olympics: they made videos in which they were wearing the Bing Dwen Dwen headdress special effect by placing their face in Bing Dwen Dwen memes. A pre-formed template like this may well have made disparate users feel connected.

Livestreaming can also function as an important communication tool. In this media form, users can acquire more knowledge about media personae through self-disclosure (e.g., talking about their personal experiences at work or in their family life) [19]. Additionally, viewers can easily approach media personae nearly synchronously during live events when there are not too many other viewers, thus facilitating instant responses from given media personae. Mutual awareness can therefore be invoked, and users’ psychological needs can be met via such a seemingly equal establishment of online interaction with otherwise unreachable media personae [20]. Researchers have found, for example, that TikTok users who were mourning felt connected and comforted when they engaged with a live host [21].

Given these distinguished functionalities, interactions on short-form video platforms can be seen as a creative form of online interaction: users are encouraged to follow media personae for a long time and build relationships with them through various, seemingly two-way, communication modes (e.g., participating memes and livestreaming).

Hopelessness and media use

Hopelessness constitutes two main elements: (a) pessimistic future-oriented thinking and (b) the perception of an impassable impediment to goal achievement [22]. Much media-related research has correlated this negative mental status with virtual interactions in a given medium. For example, scholars have long been concerned with the possibility that improper media use can cause negative outcomes such as hopelessness and depression [23]. Kubey [24] suggested that aging viewers who are exposed to negative depictions of older persons may begin to feel unwanted.

However, there is also evidence suggesting that the association between media use and psychological issues could be reversed. Especially since the 1970 s, numerous uses and gratifications studies have suggested that users’ characteristics and purposes for consuming media play a crucial role in media involvement [25, 26]. Consequently, vulnerable individuals may seek virtual relationships (PSRs) as functional alternatives. For example, previous empirical evidence suggests that individuals experiencing loneliness can approach PSRs for help and thereby fulfill their interpersonal needs [27]. This is because the virtual space provided by media can help individuals who are vulnerable and sensitive to rejection to enjoy the experience of real social interactions [28]. In this respect, vulnerable audiences may turn to viewer-performer relationships as a means of engaging with issues related to identity and self-concept, sometimes encountering experiences they have not had in real life [29].

Nevertheless, an understanding of the ways in which hopeless individuals’ motivations can generate positive aspects of self-concept formation—such as well-being and self-identity via the viewer-performer bond when individuals use short-form video platforms—is still missing. The present study addressed this gap in the literature by exploring the underlying processes of these connections.

Hopelessness and PSRs on short-form video platforms

As previously mentioned, examinations of the association between deficit viewers and media personae indicate that the parasocial experience is the most observed phenomenon in virtual interactions [27]. Horton et al. [1] first used the term “parasocial interaction” to describe a one-sided relationship between users and media personae that exists in the user’s mind as a belief that they have direct interactions with one other. Later, parasocial researchers expanded the concept and differentiated between parasocial interactions (PSIs) and parasocial relationships (PSRs). Specifically, whereas PSIs can be defined as imagined interactions that only occur during media exposure, PSRs refer to deeper relationships that may start during viewing but persist beyond the context of media exposure [2, 30]. That is, in contrast to a PSI, a PSR tends to be more similar to real relationships with enormous investments in time, emotion, or money [31]. Once users have established a PSR, it does not disappear even if the users temporarily stop paying attention to the media personae; it remains in the users’ minds and is ready to provide help to users whenever they need it. It has thus been suggested that health-related research should focus more on PSRs than PSIs because users can obtain more potentially positive effects from engagement with media personae in such enduring relationships [32].

Because parasocial relationships (PSRs) resemble face-to-face social interactions, research on PSRs often draws from interpersonal communication theory, particularly the substitution hypothesis [33]. A notable advancement in this area is the theoretical model of the development of parasocial relationships proposed by Tukachinsky et al. [34], which synthesizes sixty years of PSR studies and incorporates Knapp’s model of relationship development [35, 36]. Unlike earlier studies that often treated PSRs as static constructs or one-time reactions, this model conceptualizes PSRs as dynamic, evolving experiences. It is also the first to place PSRs at the center of analysis, offering a comprehensive framework that captures the full trajectory of PSR development [31, 37].

According to this theory, the motivation of satisfying special needs serves as an antecedent to the formation of PSRs [34]. Specifically, users who experience feelings of helplessness or low self-worth in real life may actively seek out media content that provides comfort, encouragement, or validation. For example, someone experiencing helplessness may be compelled to turn to PSRs for help [38]. Importantly, this PSR is particularly likely to occur between users and the media personae they previously followed. This is because these media personae are more trusted for inferior individuals. Thus, PSRs with media personae, especially those whom users have been constantly following, can be used as meaningful tools for individuals with low self-evaluation and negative moods: they can help those who feel hopeless overcome mental and emotional challenges [39].

This process of engaging with PSRs as a way to navigate or mitigate feelings of hopelessness may be especially facilitated on short-form video platforms, given their distinctive patterns of interaction. The theoretical model of the development of PSRs asserts that accessibility (the extent to which media personae would like to interact with users) has great potential to shape users’ experience of closeness in such relationships [34]. For example, live-streaming allows short-form video users to engage in more meaningful communication with media personae; during live events, viewers can directly communicate with media personae and participate in quasi-synchronous conversations [40]. As such, hopeless individuals may regard short-form video platforms as a means of attaining comfort: they may seek help from vloggers with whom they develop PSRs owing to the similarities between PSRs on short-form video platforms and real-life social relationships. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

PSRs and self-identity/well-being

Self-identity is conceptualized as a core component of individual cognitive processes in cognitive psychology [41]. This concept focuses on how a developing individual endowed an attitude toward himself -or herself [42]. For example, whether or not “the individual feels certain about what he/she should do with her life” and “feels proud to be the sort of person he/she is”. If the positive outweigh the negative, individuals are better equipped to handle future difficulties [43]. As such, self-identity as cognition becomes a crucial element of mental health because it can guide individuals’ behaviors, especially when encountering difficulties [44].

Self-identity is traditionally formed through the social groups [45]. In the social media era, however, individuals’ self-identity is increasingly shaped not only by interpersonal interactions but also by mediated experiences—especially sustained engagement with media personae. A key pathway for the role of mediated experiences on self-identity lies in the activation and intensification of PSRs, through which users interact with media personae in socially meaningful ways that shape self-perception and identity [46].

According to the theoretical model of the development of parasocial relationships, as a PSR intensifies, users develop strong trust in the media persona and reduce psychological resistance to their messaging [34, 47]; Over time, these figures may be internalized as role models, shaping users’ opinions and self-understanding [48]. This cognitive alignment suggests that stronger PSRs can be associated with users’ self-identity by offering emotional resonance and behavioral guidance.

Building on this foundation, recent research suggests that short-form video platforms like TikTok may further amplify these effects. With affordances such as algorithmic curation, short-form storytelling, and high-frequency self-disclosure, these platforms foster repeated exposure to familiar media personae. Such features have facilitated a shift from the “networked self” to the “algorithmic self,” where identity is no longer solely formed through social dialogue but through recursive interactions with algorithm-selected representations of the self [49]. As algorithms continuously surface media personae aligned with users’ prior behavior, they reinforce perceived intimacy and similarity—key elements in PSR reinforcement. In this context, PSRs become both emotionally and algorithmically conditioned, deepening their influence on users’ evolving sense of self. These effects may be further enhanced by immersive features such as livestreaming and participatory culture (e.g., memes, co-creation), which promote sustained engagement and co-construction of meaning between users and media personae. In light of these dynamics, we proposed the following hypothesis:

As an important branch of media psychology research, parasocial research also explores how parasocial experiences enhance user well-being through various media [50]. In general, well-being is conceptualized through two major paradigms: hedonic and eudaimonic. The hedonic approach focuses on subjective well-being, emphasizing individuals’ evaluations of their lives based on positive affect, low negative affect, and a sense of life satisfaction [51]. In contrast, the eudaimonic paradigm emphasizes functional well-being, referring to individuals’ capacity to “do well” in life—through personal growth, purpose, autonomy, and self-actualization—rather than simply “feel good” [52]. Despite this distinction, media scholars often adopt an integrative perspective that combines both paradigms. For instance, Keye describes well-being as “flourishing” [53], while Seligman [54] refers to it as living “a full life.” These integrated notions correspond closely with emotional outcomes associated with PSRs: on one hand, increased happiness and satisfaction may arise from affective investment in media personae [27]; on the other hand, deeper feelings of purpose, meaning, and belonging may emerge from long-term parasocial bonds [55].

As previously noted, short-form video platforms offer novel forms of relationship; therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate how PSRs can fulfill users’ need to improve their aspirational capability. For example, by posting memes rather than reading comments, viewers may find it easier to foster a sense of belonging and enhanced emotional effects [21]. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

The term PSR implies an online, one-sided, long-term relationship between media personae and viewers [3]. According to PSR theory, such relationships typically evolve through two main stages [56]. In the first stage, viewers’ psychological needs interact with media personae’s self-disclosure, fostering perceived intimacy through curated and authentic content [31]. In the second stage, PSRs may reduce viewers’ reactance and counterarguing, thereby influencing their cognition and emotion [34]. That is, PSRs act as an important mediator between motivations and attitudes or psychological feelings. While several empirical studies have identified these two processes [10, 57, 58], none has focused on the psychological effects of PSRs among users of short-form video platforms experiencing hopelessness. Having acknowledged the unique features of short-form video platforms in terms of self-disclosure, patterns of interactions, and memes [40], users experiencing experiencing hopelessness may turn for help to PSRs with vloggers whom they closely follow for help. Such a PSR can also be related to positive outcomes for the user’s self-identity/well-being. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Perceived similarity and PSRs

Perceived similarity refers to an individual’s subjective perception that another individual is similar to them [59]. The theoretical model of the development of parasocial relationships indicates that viewers’ perceptions of similarity between them and given media personae can affect their PSR process [34]. Media users may record the quality of relationship schemata with media personae they encounter, creating a mental representation of their relationship that includes similarities between them (the viewer) and media personae [60]. These relationship schemata will be activated and recalled before the formation of PSRs. If the relationship schemata fit viewers’ situational needs, the likelihood of continuing the relationships with the corresponding media personae will increase [61].

This explanation is related to the similarity-attraction mechanism. Specifically, individuals—especially those who are vulnerable—tend to choose to make connections with strangers who seem similar to them on first acquaintance [13]. This is because the perception of similarities reduces the time cost required for accepting new ideas, and therefore increases the effectiveness of subsequent communication between media personae and viewers. Prior studies have indicated that this pattern also applies to social media [12]. For example, participants who held similar political beliefs to Trump were found to be more susceptible to forming parasocial relationships with him and show greater agreement with his viewpoints on social media [62]. Because individuals experiencing hopelessness are more vulnerable and have a stronger yearning for comfortable and meaningful communication, the positive association between hopelessness and PSRs may be amplified among those who perceive greater similarity. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H4: Perceived similarity positively moderates the relationship between hopelessness and PSRs, so that the positive relationship between hopelessness and PSR is stronger for individuals with higher perceived similarities.

H5a-b: Perceived similarity moderates the indirect effect of hopelessness on (a) self-identity and (b) well-being via PSRs, such that the more similarities individuals perceive, the stronger the positive relationship between hopelessness and self-identity/well-being.

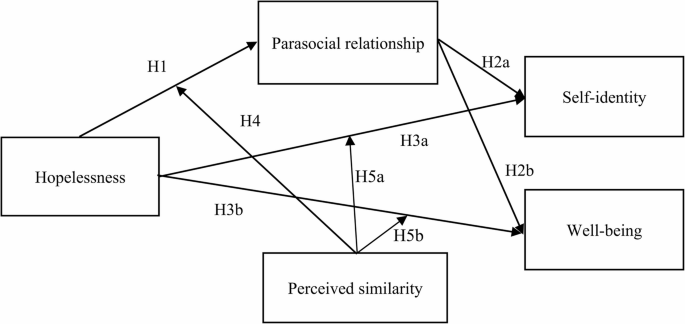

The proposed research model with all the hypotheses can be seen in Fig. 1.

Proposed research model with all hypotheses