Great white sharks have always sat near the top of the food chain. But in the waters of the Gulf of California, a team of apex predators is shaking things up.

A pod of killer whales has been filmed hunting and killing juvenile great white sharks, and then eating just one body part – the liver.

This isn’t random violence or chaos in the sea. It’s a coordinated strategy with precision and purpose. And it could signal a shift in how these powerful predators interact in warming oceans.

Dangerous technique with a smart twist

The orcas aren’t just chasing down baby sharks and ripping them apart. They’re using a smart, practiced move – turning the shark upside down. That sends the shark into a frozen state called tonic immobility. It’s like a forced paralysis.

Once flipped, the shark can’t defend itself, and the orcas waste no time extracting its liver, a nutrient-packed organ loaded with fat and energy.

In one recorded event from August 2020, five orcas worked together to take down two young great white sharks. They herded them to the surface, flipped them, and then took them underwater. Moments later, the whales returned with the sharks’ livers in their mouths.

A second hunt in August 2022 followed the same pattern. This time, one juvenile was pushed on its back, bleeding from the gills.

The orcas were seen eating the liver shortly after. These weren’t flukes. They were team efforts, and they followed a specific plan.

Orcas pass down hunting techniques

The group responsible is known as Moctezuma’s pod. Scientists recognize them by their dorsal fins. This pod has been spotted before, feeding on rays and even taking on bull and whale sharks. Now, they’ve turned their attention to young great whites.

“I believe that orcas that eat elasmobranchs – sharks and rays – could eat a great white shark, if they wanted to, anywhere they went looking for one,” said marine biologist Erick Higuera Rivas, project director at Conexiones Terramar and Pelagic Life.

“This behavior is a testament to orcas’ advanced intelligence, strategic thinking, and sophisticated social learning, as the hunting techniques are passed down through generations within their pods.”

This technique, flipping sharks and going straight for the liver, may be less risky when used on younger sharks. Juvenile great whites are smaller and less experienced. That makes them easier targets.

The damage on the carcasses suggests orcas are developing a way to get the job done while avoiding injury. A bite from a great white is no small risk – even for an orca.

Shark response: Flee or freeze?

Adult white sharks usually respond fast when orcas are around. They leave their gathering spots and may not come back for months. But young sharks don’t seem to know better.

“This is the first time we are seeing orcas repeatedly target juvenile white sharks,” said Dr. Salvador Jorgensen of California State University.

“Adult white sharks react quickly to hunting orcas, completely evacuating their seasonal gathering areas and not returning for months. But these juvenile white sharks may be naive to orcas.”

According to Dr. Jorgensen, it is not yet clear whether white shark anti-predator flight responses are instinctual or need to be learned.

That question could matter a lot as ocean conditions continue to shift. If shark pups don’t inherit the instinct to flee, they might keep falling victim to these orca tactics.

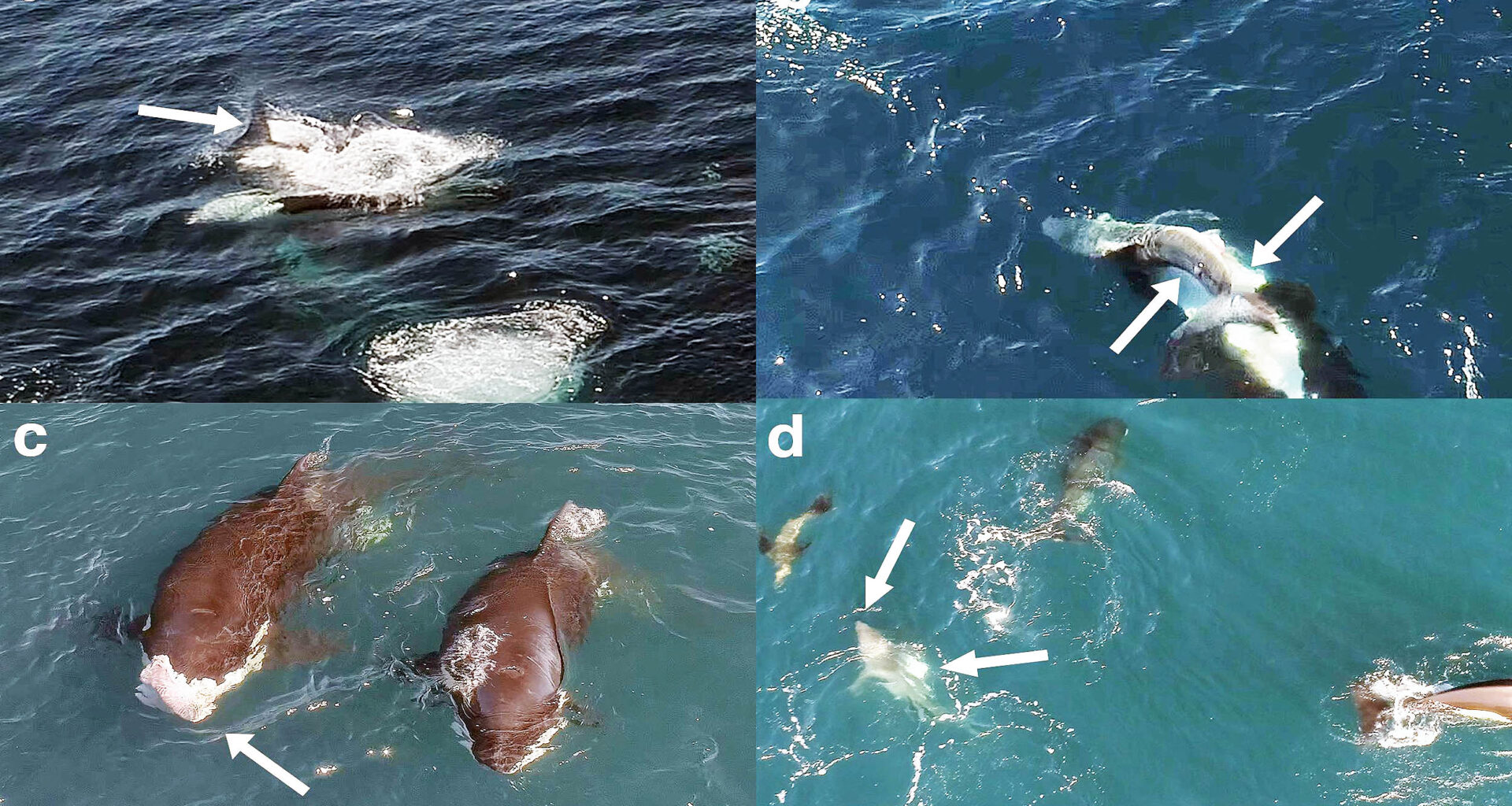

Sequence of the killer whales attacking the first juvenile white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) on 15th of August 2020. Identifying features of the species are visible (denoted by white arrows): (a) The crescent-shaped tail. (b) The distinctive caudal peduncle and keels, large triangular first and small second dorsal fins are visible. (c) The two-lobed liver is being hold by the orca. (d) The moderately stout, torpedo-shaped body is visible, and the partially exposed liver is seen on the right side of the second shark attacked. Photos credit: Jesús Erick Higuera Rivas/Frontiers in Marine Science. CLICK IMAGE FOR VIDEONew hunting grounds for orcas

Sequence of the killer whales attacking the first juvenile white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) on 15th of August 2020. Identifying features of the species are visible (denoted by white arrows): (a) The crescent-shaped tail. (b) The distinctive caudal peduncle and keels, large triangular first and small second dorsal fins are visible. (c) The two-lobed liver is being hold by the orca. (d) The moderately stout, torpedo-shaped body is visible, and the partially exposed liver is seen on the right side of the second shark attacked. Photos credit: Jesús Erick Higuera Rivas/Frontiers in Marine Science. CLICK IMAGE FOR VIDEONew hunting grounds for orcas

Changes in the Pacific Ocean could be making all of this more common. Climate events like El Niño are shifting where young white sharks live.

Scientists believe nursery zones may now be stretching into the Gulf of California – right into Moctezuma’s pod’s backyard.

That means these orcas might have access to a new, seasonal source of high-energy prey. Each year, fresh batches of juvenile sharks could be swimming into the wrong neighborhood.

But right now, it’s not clear whether orcas are regularly hunting white sharks or just going after the juveniles when the opportunity shows up.

“So far we have only observed this pod feeding on elasmobranchs,” said Dr. Francesca Pancaldi of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas (CICIMAR).

“There could be more. Generating information about the extraordinary feeding behavior of killer whales in this region will lead us to understand where their main critical habitats are, so we can create protected areas and apply management plans to mitigate human impact.”

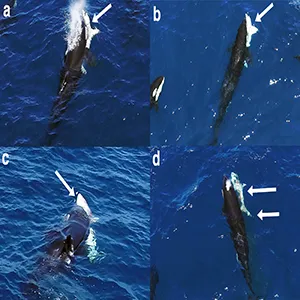

Figure 2. Sequence of the killer whales attacking a juvenile white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) on 3rd of August 2022. Identifying features of the species are visible (denoted by white arrows): (a) Large gill slits. (b) Large pectoral fins, black tip on the underside of the white shark’s pectoral, moderately stout, dark grey to bluish-grey color on the upper surface and white below. (c) Shape of curvature of the upper and lower jaws. (d) A partially exposed liver is seen on the left ventral side of the shark, as well as the upper lobe of the caudal fin. Photos credit: Jesús Erick Higuera Rivas/Frontiers in Marine Science. CLICK IMAGE FOR VIDEOShark hunting isn’t easy to study

Figure 2. Sequence of the killer whales attacking a juvenile white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) on 3rd of August 2022. Identifying features of the species are visible (denoted by white arrows): (a) Large gill slits. (b) Large pectoral fins, black tip on the underside of the white shark’s pectoral, moderately stout, dark grey to bluish-grey color on the upper surface and white below. (c) Shape of curvature of the upper and lower jaws. (d) A partially exposed liver is seen on the left ventral side of the shark, as well as the upper lobe of the caudal fin. Photos credit: Jesús Erick Higuera Rivas/Frontiers in Marine Science. CLICK IMAGE FOR VIDEOShark hunting isn’t easy to study

The team hopes to do a larger survey to study what this pod is really eating and how often they hunt sharks. But that kind of research isn’t easy. Orca hunts are rare and unpredictable.

Fieldwork on the open ocean costs money. And the evidence – like half-eaten sharks – doesn’t stay around for long.

Still, what’s been seen so far suggests that orcas may have more advanced hunting strategies than anyone thought. And they may be using their intelligence to adapt to an ocean that’s changing fast.

The full study was published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Credit for these amazing photos goes to Jesús Erick Higuera Rivas/Frontiers in Marine Science

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–