PFFs represent a challenging complication following THA and hemiarthroplasty and are expected to continue contributing substantially to the orthopaedic workload, as joint arthroplasty has become increasingly common. This trend is driven by an aging population, with a projected 150% increase in people over 65 years of age over the next 30 years [22].

In our study, the 30-day mortality rate was 7.5%, which is consistent with reports in the literature ranging from 3.3 to 9.3%. The one-year mortality rate was 16.4%, which is also in line with published data (13.4–22.3%) [12,13,14]. Our study only assessed 30-day and one-year mortality rates, but previous research has reported a three-year mortality rate of 48%, with higher mortality rates with increasing fracture severity [14]. The COMPOSE study reported 30-day and one-year mortality rates of 5.2% and 21.0%, respectively [23]. Relative survival following PFF has been shown to be worse than that after other indications for revision THA, including aseptic loosening, infection or dislocation [24]. The elevated mortality rate in our cohort is not surprising, given the advanced mean age of nearly 80 years and a mean CCI of 4.39. Patients with a CCI greater than or equal to 5 had significantly higher one-year mortality rates, supporting previous evidence linking a greater comorbidity burden with poorer outcomes [18, 25]. Advanced age is a well-established risk factor for PFFs [4, 26]. In contrast to previous findings within the literature, sex was not associated with increased PFF risk in our cohort, which aligns with the findings of only one prior study [26].

Discharge destination data highlight the long-term impact of PFFs on independence. A total of 59 patients were discharged to nursing homes or offsite rehabilitation facilities, whereas 12 patients were admitted initially from nursing homes. The COMPOSE study reported that 61% of patients admitted initially from home were discharged back to their own residence [23]. At the one-year follow-up, 20 patients were residing in nursing homes—representing a 16% increase and highlighting the profound effect on patient independence. While institutionalization has not been widely studied in PFFs, hip fractures alone are associated with rates of 10–20% [27].

Our median length of hospital stay was 14 days, which is comparable to the 15 days reported in the COMPOSE study [23]. Length of in-hospital stay is a major contributor to healthcare costs in these PFFs, accounting for up to 80% of total costs in one study, which reported a mean length of stay of 36 days [1]. In a frail elderly cohort, prolonged hospital stays are often unavoidable due to the recovery process, unlike elective or revision THA, where discharge planning can typically be arranged prior to admission.

With respect to surgical management, more than 75% of patients underwent fixation alone rather than stem revision. Fixation-only strategies are associated with reduced blood loss, shorter operative times, and decreased lengths of stay because of their less invasive nature [28]. Almost half of the fractures were classified as Vancouver B2. While the COMPOSE study reported 55% B2 fractures, 77% of these fractures underwent revision, whereas only 24% did in our center [23]. The reasons for choosing ORIF over revision was not recorded at the time of surgery, which limits our ability to determine whether surgical decisions followed standard guidelines. One patient required proximal femur replacement because of compromised bone quality, precluding reliable fixation or revision. Fracture pattern type A fractures were predominantly managed conservatively (88%), which is consistent with standard practice, unless the trochanter fracture is displaced by more than 2 cm or the prosthesis is unstable [29]. None of the patients in our cohort required revision surgery, in contrast to the COMPOSE study which reported a one-year reoperation rate of 5.6% [23]. The low revision rate in our study may be due to the short follow-up, or careful preoperative planning of procedures. All operations were performed by consultant orthopaedic surgeons via conventional techniques, without the assistance of artificial intelligence or robotic systems. While robotic-assisted THA has generally demonstrated superior accuracy and safety compared with conventional approaches [30, 31], its application has not yet been studied in the management of PFFs.

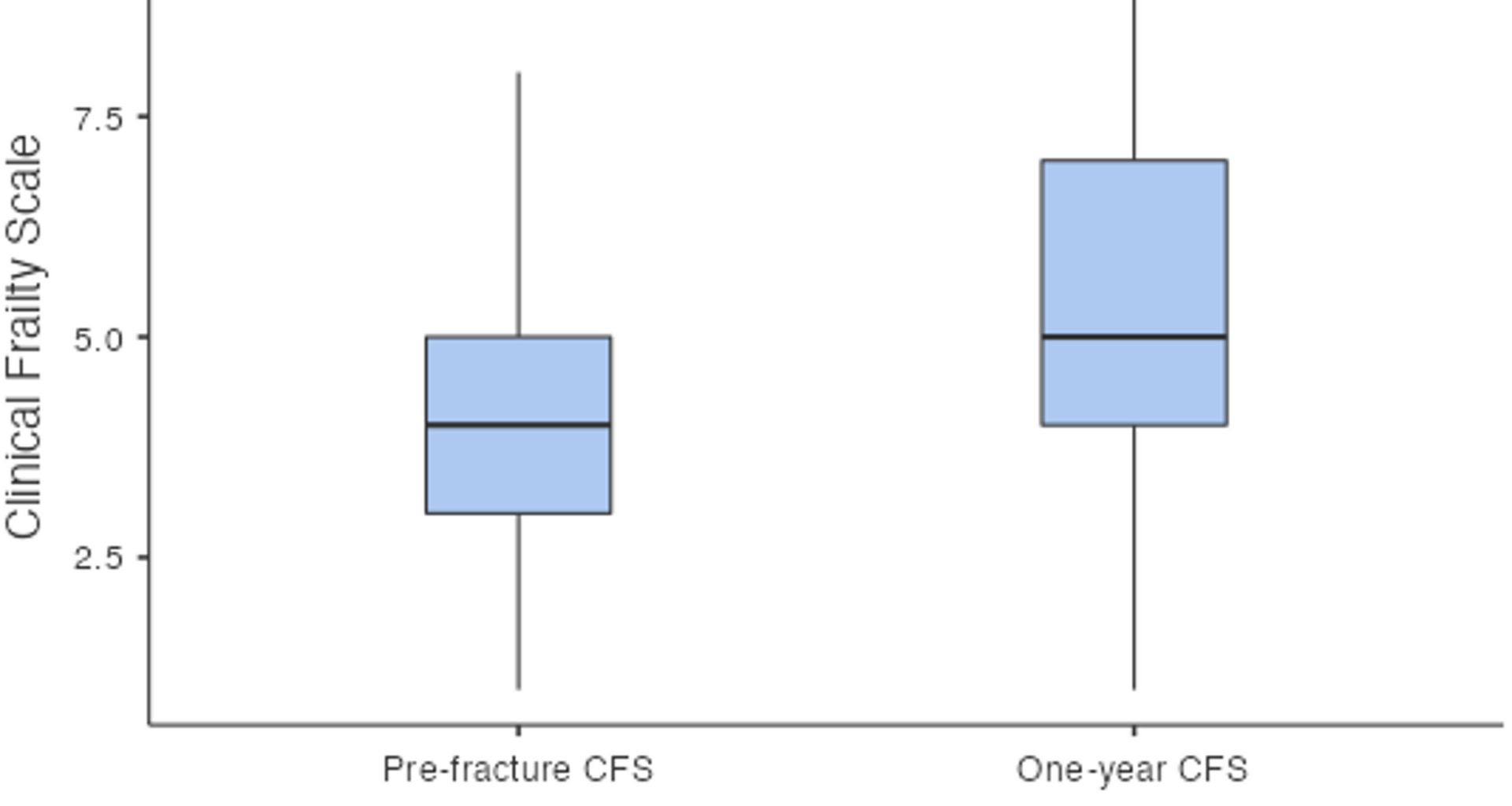

Functionally, our cohort experienced significant declines in mobility and frailty at one year. The median NMS decreased from 7 to 5, reflecting reduced mobility. Previous studies have shown that it is difficult for patients to regain their prefracture walking ability, with a substantial portion relying on walking aids and approximately 58% failing to return to their prefracture walking status [13]. NMS has been shown to decrease by approximately 1.5 from the preoperative period to the last follow-up at 3 years [14]. Similarly, the median CFS increased from 4 to 5, indicating greater frailty at one year. Frailty has been linked with increased mortality [16], yet its change has not previously been quantified via a numerical scale. Self-sufficiency scores and functional scores such as the Harris hip score, indicate better outcomes for Vancouver A fractures than for B or C fractures [14]; however our study did not perform sub-group analyses. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify changes in both mobility and frailty numerically for PFF patients after one year, demonstrating that even with appropriate surgical management, patients rarely return to their prefracture functional status.

Our study is not without its limitations. As a retrospective study design, it is dependent on the quality and completeness of existing records. As it was conducted at a single center, the sample size was relatively small. Excluding patients from the functional outcome analysis who died within one year may have introduced survivorship bias, potentially leading to an overestimation of postfracture mobility and frailty by selectively analyzing a healthier subset of the cohort. The Vancouver classification was assessed by two expert orthopaedic consultants, but human error remains possible. Although the CFS and NMS are simple scoring tools, the lack of consistent investigators may have introduced inter-rater bias. Statistical analyses were unadjusted and did not account for covariates such as preoperative functional status or indication for primary arthroplasty; these factors likely influenced outcomes. Analyzing outcomes according to the Vancouver classification could provide a clearer understanding of how fracture type individually affects mobility and frailty. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to compare prefracture and one-year mobility and frailty in PFFs on a numerical scale. Future studies could compare the outcomes in PFFs with those of conventional hip fractures.