The Biodome seen from the observatory at the Olympic Stadium. Image © Guilhem Vellut via Wikipedia under license CC BY 2.0

The Biodome seen from the observatory at the Olympic Stadium. Image © Guilhem Vellut via Wikipedia under license CC BY 2.0

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1035861/the-montreal-biodome-from-olympic-velodrome-to-a-space-for-life

The history of the Olympic Games, while marked by athletic achievement, is consistently contrasted by infrastructure challenges. Across host cities, from Athens to Rio and Beijing, similar issues arise: significant cost overruns and the complex issue of legacy. The big question is: What is the best viable long-term use for purpose-built sport venues? Montreal’s 1976 Games shared this fate after building an Olympic Park that faced heavy criticism for cost overruns and debt from specialized construction. Post-Games, venues like the Montreal Velodrome risked becoming a financial burden. However, the city demonstrated a proactive response by proposing the transformation of the building into a thriving civic asset that now stands as an internationally recognized example of successful Olympic venue repurposing.

To host the Olympics, the city commissioned French architect Roger Taillibert to design an Olympic park that included a stadium, a swimming pool, and a velodrome. The latter hosted both track cycling and judo events during the Games; however, for many years after the Olympics ended, the facility faced the challenge of having no defined permanent post-Games purpose. During that time, it hosted other major events, such as “Les Floralies Internationales de Montréal” in 1980, an international horticultural exhibition. In 1988, the city explored the possibility of transforming the velodrome into The Biodome: an environmental enclosure that would use the existing light-filled shell of the velodrome to house and display multiple, self-contained, recreated, and climate-controlled biospheres.

The project proposed four distinct ecosystems from the Americas: the Tropical Forest (modeled on South American rainforests), the Laurentian Forest (North American wilderness), the Saint Lawrence Marine Ecosystem (an estuary habitat), and the Sub-Polar Region (divided into Arctic and Antarctic zones). The concept originated from Pierre Bourque, then director of the Montreal Botanical Garden and future mayor of Montreal. In 1989, construction began on the renovation. After three years of intensive work, the Biodome officially opened to the public in 1992, and its execution was recorded in a documentary called The Glass Ark published by Bernard Gosselin in 1994. Today, the structure forms part of the largest natural science museum complex in Canada called “Espace pour la Vie“, which also includes an insectarium, botanical garden, planetarium, and the repurposed geodesic dome (US pavilion) from the Expo 67: The Biosphere.

Related Article From White Elephants to Sustainable Venues: The Evolving Story of Olympic Architecture  One of the ecosystemts inside The Biodome. Image © James Brittain

One of the ecosystemts inside The Biodome. Image © James Brittain

The commitment to the structure’s longevity continued in 2014 when Montréal Space for Life initiated the “Biodôme Migration” project: a major renovation launched through an international competition. The central architectural goal was to renew the facility’s internal complex ecosystems (animals, plants, light, energy) and enhance the visitor experience. The winning team was a consortium led by KANVA / NEUF architect(e)s for the architectural design. After a two-year closure, the entire building was restored, introducing a modernized visitor journey, successfully updating the original 1992 conversion.

Interior of the Biodome after the 2014 renovation . Image © Marc Cramer

Interior of the Biodome after the 2014 renovation . Image © Marc Cramer The new skin designed wrapping around the ecosystems designed by KANVA / NEUF architect(e)s. Image © Marc Cramer

The new skin designed wrapping around the ecosystems designed by KANVA / NEUF architect(e)s. Image © Marc Cramer

The Velodrome’s creative transformation can serve as a compelling model for the current mandate of sustainability in Olympic planning. Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier, and Daniel Lunn published a study that analyzed Olympic costs and explained that strict schedules and legally binding obligations discourage cities from abandoning projects, even when cost overruns are unavoidable. This situation has discouraged bidding in recent years, which is why the IOC’s 2023 recommendations for future games emphasize that hosts must put sustainability and legacy at the heart of their proposals, adapting the games to the city rather than the city to the games.

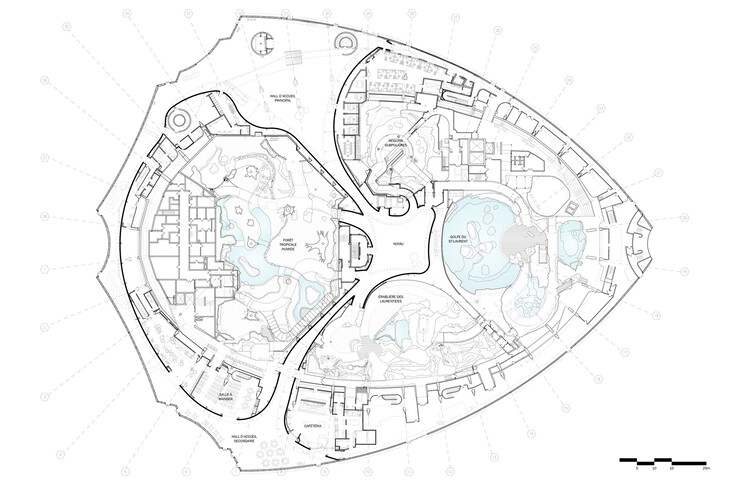

Floorplan of The Biodome. Image © KANVA

Floorplan of The Biodome. Image © KANVA

In that context, the Paris 2024 Olympics represent the first to really embrace this philosophy. They used 95% existing venues, in a strategy to reduce environmental footprint and avoid the “white elephant” problem plaguing previous games. Also, Paris leveraged iconic landmarks rather than building new permanent structures. For example, the Eiffel Tower area hosted beach volleyball, the Champs-Élysées hosted cycling competitions, and Versailles hosted equestrian events. These and other temporary structures, like Le Grand Palais Éphémère, were designed for dismantling after the Games, leaving no permanent footprint while still providing world-class competition spaces.

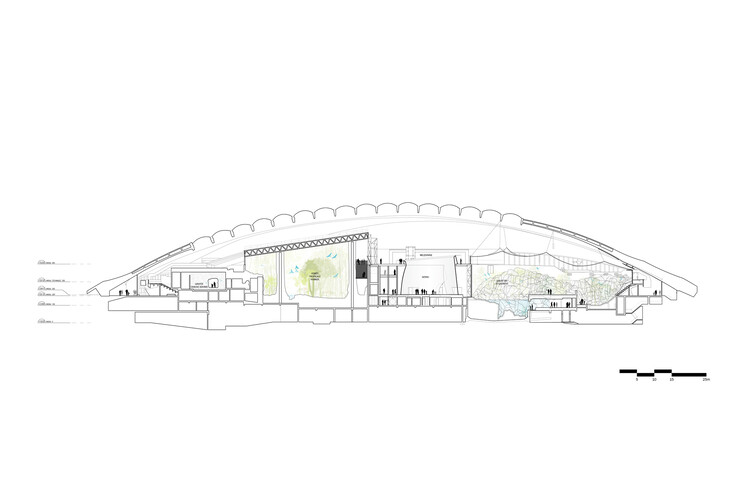

Section of The Biodome. Image © KANVA

Section of The Biodome. Image © KANVA

The Montreal Velodrome’s transformation from a specialized sporting venue into a public science center offers a solution to the persistent Olympic legacy challenge. This outcome, ahead of its time, directly addressed the IOC’s updated mandate, which emphasizes that future hosts must prioritize sustainability and long-term utility. The conversion of a single, expansive shell structure into four distinct, climate-controlled biospheres highlights that the success of post-Games planning relies fundamentally on architectural creativity and adaptability.

Main entrance of the Biodome after its renovation. Image © James Brittain

Main entrance of the Biodome after its renovation. Image © James Brittain

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Building Less: Rethink, Reuse, Renovate, Repurpose, proudly presented by Schindler Group.

Repurposing sits at the nexus of sustainability and innovation — two values central to the Schindler Group. By championing this topic, we aim to encourage dialogue around the benefits of reusing the existing. We believe that preserving existing structures is one of the many ingredients to a more sustainable city. This commitment aligns with our net-zero by 2040 ambitions and our corporate purpose of enhancing quality of life in urban environments.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

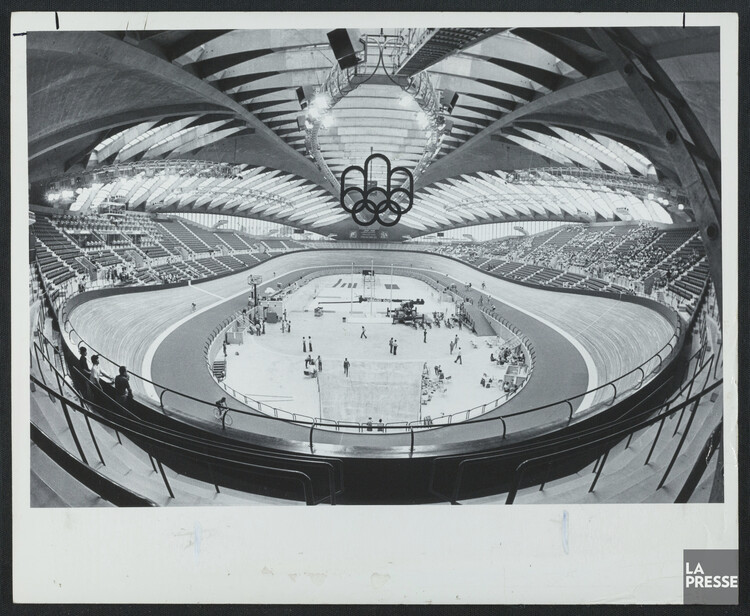

The velodrome ready for the 1976 Olympic Games. Image © Fonds La Presse – Archives nationales à Montréal via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

The velodrome ready for the 1976 Olympic Games. Image © Fonds La Presse – Archives nationales à Montréal via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Japanese visitors in company of Pierre Bourque at the site of the Biodome in 1992 . Image © Michel Gravel via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Japanese visitors in company of Pierre Bourque at the site of the Biodome in 1992 . Image © Michel Gravel via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec