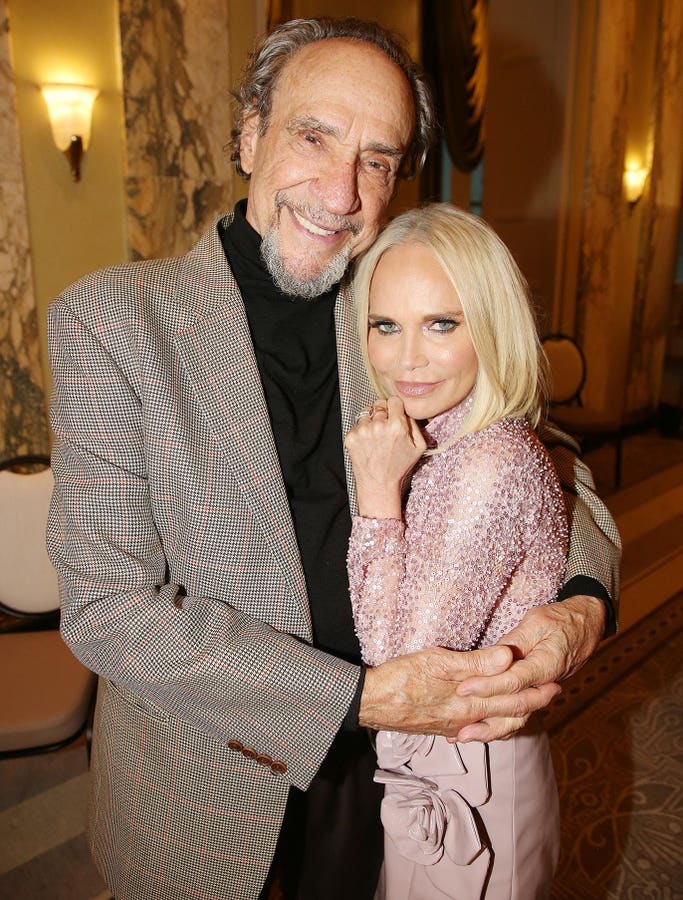

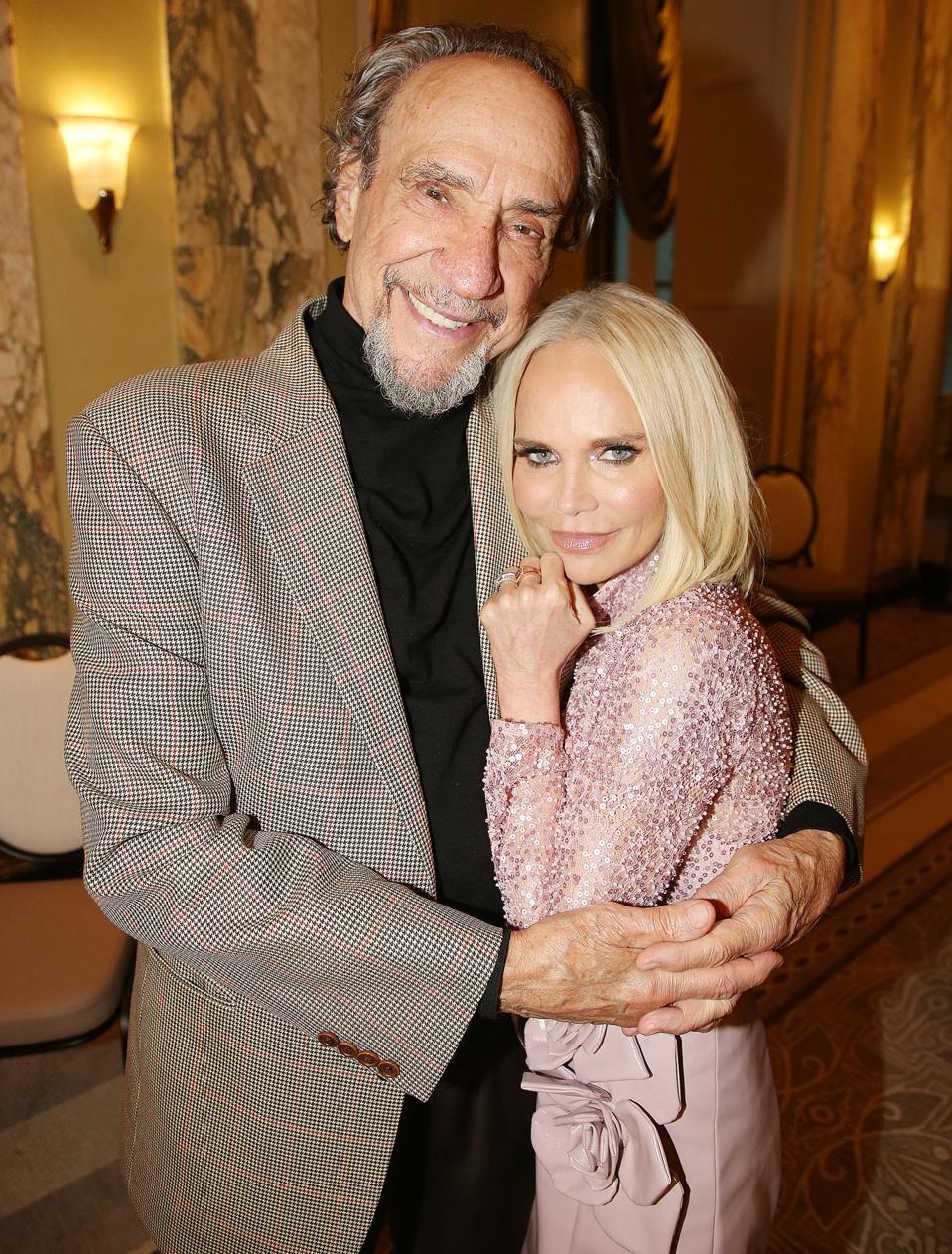

F. Murray Abraham and Kristin Chenoweth pose at a photo call for the upcoming Broadway musical “The Queen of Versailles” at The Waldorf Astoria Hotel on September 18, 2025 in New York City. (Photo by Bruce Glikas/Getty Images)

Bruce Glikas/Getty Images

The Broadway opening this past week of the musical “The Queen of Versailles” provides opportunity to reconsider one of the most colorful and unusual business stories of the early 2000s.

The musical is based on the widely viewed 2012 documentary, “The Queen of Versailles.” The documentary focuses on David Siegel, the founder and long time president of the Westgate Resorts timeshare company (the largest timeshare company in the world) and his wife Jackie, and their attempt to build a replica of the palace of Versailles in Orlando, Florida. At an envisioned 90,000 square feet, the Orlando palace would be the largest private home in America.

The Siegels’ story has been portrayed as one of excess, greed, inequality and pursuing empty goals: the lenses through which Hollywood and Broadway today see much of American business. There are elements of each of these themes in their story.

Yet, other themes are present that make the story a more complex and compelling one: David’s entrepreneurial drive not to let Westgate Resorts go under in 2008; Jackie’s own entrepreneurship in Versailles and other ventures; their joint determination to push forward despite numerous setbacks without whining, complaining or blaming the economic system.

With the attention that “The Queen of Versailles” is gaining, it is worth saying a few words about these other overlooked themes. And there is a further theme related to Dr. Samuel Johnson’s still relevant observation on wealth from the eighteenth century. “There are few ways in which a man can be more innocently employed than in getting money,” Dr. Johnson tells his biographer Boswell. This too is part of the story.

David and Building the World’s Largest Timeshare Company

David started his first real estate firm, Central Florida Investments, in 1970 in his garage. In the early 1980s, he saw an emerging market opportunity in the timeshare concept, and went after it. He opened his first timeshare resort in 1982, the 16-unit Westgate Vacation Villas in Orlando.

Over the next two decades the company grew quickly, reaching 14 resorts by the early 2010s: in Las Vegas, Park City, Manhattan, Williamsburg, Branson, and Myrtle Beach. As it did so, it became the largest time share business in the world. It also came to be one of Florida’s largest private employers, with over 3500 employees. In the documentary, we meet workers in sales, call centers, construction and operations.

When the documentary starts, Westgate’s business is booming—additional resorts, jobs added, expanded territories. Then in September 2008, as the American financial system teeters, suddenly everything changes. The timeshare business is built on credit, and Westgate is heavily leveraged with bank loans. The banks begin to call in the loans, and Westgate is forced to lay off workers and dramatically cut back operations. David is faced with losing the company he has built over 26 years.

David and Jackie sell their assets (including their private plane), cut back on spending, transfer the children to public schools. Though David is now 73 years of age, he sets out on a round-the-clock effort to try to save the company.

Over the next five years, David succeeds, and Westgate revives. He is able to find new financing and additional investors. As the national economy recovers, the timeshare market rights itself.

“Life balance” advocates would have advised David in 2008 that his life was out of whack. At 73, he should be relaxing, “spending more time with his family,” letting go of the business. Fortunately, for the local economies in which David invested, he is an entrepreneur and follows a different path. He continues to take risks and build resorts, and employ thousands of operations and construction workers. Neither the documentary nor the musical truly capture this theme.

Jackie’s Entrepreneurship and the Building of Versailles

Jackie is an entrepreneur in her own right. We are introduced to her as a former beauty queen (Mrs. Florida, 1993), though we come to learn that she has a degree in computer engineering from the Rochester Institute of Technology and was employed early in her career at IBM.

We see a lot of Jackie shopping and buying things. Jackie is a shopaholic. Her house is filled with clothes and toys and furniture that are hardly used. A warehouse nearby stores her purchases of antique furniture and goods from Europe.

To focus on her compulsive shopping, though, is to miss her other roles in business and community ventures and as the prime mover in building Versailles. She establishes a thrift store, Ocoee Thrift Mart, in an abandoned former department store, selling goods at sharp discounts, as well as a charity, Locals Helping Locals. When one of her daughters, Victoria, dies of a drug overdose she establishes Victoria’s Voice, a foundation to address substance abuse disorders.

Her main project is the building of Versailles. From one perspective, it is a ridiculous project that calls into question the sanity of the builder: envisioned with more than 5 kitchens, a 35 car garage, a British style pub, a skating rink and gym, two outdoor pools and three indoor pools, and on and on.

But, as we watch Jackie design the house, what she is designing is less a house than an attempted work of art, with a great deal of attention to craft and her ideas of beauty. She coordinates the colors of the wallpaper in the “morning kitchen” with the colors of the birds to be in the kitchen birdcage. She carefully picks out the vases and paintings to be placed around the house, the gold leaf in the ballroom, the flamingos on the grounds. Whether her vision of the house as art or her ideas of beauty succeed in any way can be questioned. But over time and due to upkeep costs, her Versailles in Florida is likely to find its way into some form of public use, and her investment shared with many others.

The Siegels and Dr. Johnson’s Observation on Wealth

In anticipation of the Broadway opening of “The Queen of Versailles” New York Times columnist, Ginia Bellafante, sat down in early October with the documentary producer, Lauren Greenfield. In the resulting article, the two women portray the Siegels as representing the growing materialism, superficiality and self-centeredness of Americans (and, of course, try to tie the story to the current national Administration).

It is difficult to think of a greater misrepresentation of the Siegels’ story. The Siegels don’t claim to represent anyone but themselves. They engage in a series of community projects and good deeds— likely exceeding the good deeds of Ms. Bellafante and Ms. Greenfield. Further, the broader narrative is more accurately one of the generosity of Americans, and the vibrant network in America of volunteer and mutual support associations—more vibrant today than ever.

Which brings us back to Dr. Johnson’s observation about wealth noted above, which may be the main theme of the story. The wealth accumulation by the Siegels, if a venture of delusion, is not hurting anyone. Unlike so many activities that their critics spend time on, the Siegels are not trying to impose their political views, social views or values on others. If anything, their ventures have only created jobs and considerable economic activity for others.

The current musical need not be a time for scolding, lecturing or politicizing. Let’s just enjoy it. The leads are Kristin Chenoweth as Jackie and F. Murray Abraham as David. The songs are by composer Stephen Schwartz (“Wicked”). Who can be against this lineup.