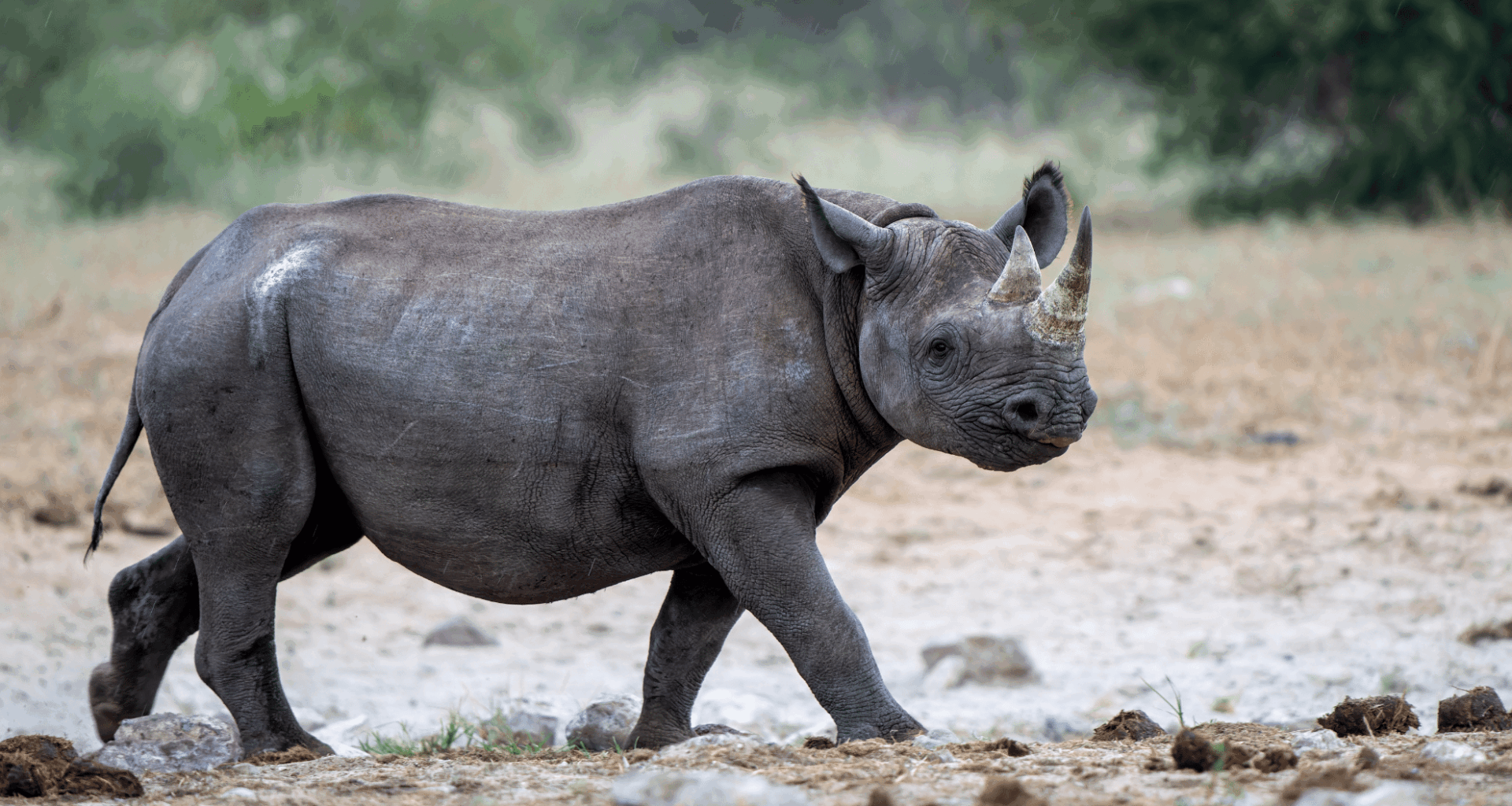

In the remote Chyulu Hills of southeastern Kenya, rangers have confirmed the birth of a critically endangered eastern black rhino calf — a remarkable event that conservationists hail as a triumph for wildlife preservation. This birth, deep within a landscape of volcanic ridges and thorny plains, signals renewed hope for one of the rarest creatures on Earth.

A Fragile Miracle In The Chyulu Hills

The discovery was first revealed by ABCNews, which reported that rangers from the Big Life Foundation and the Kenya Wildlife Service had long suspected a new calf after spotting distinct baby tracks trailing a mother rhino. Months later, camera traps confirmed the moment they had been hoping for — a female rhino named Namunyak had given birth in the wild.

The calf, estimated to be about six months old, remains shy and difficult to study.

“We haven’t gotten good enough photos to confirm that,” Baird said. “It’s usually hiding behind its mom.”

Even with limited visibility, rangers have noted signs of energy and vitality from the young rhino.

“Every time we see it, it’s moving around and being joyful — acting like you would think a cute little baby rhino would,” she said.

The Chyulu Hills, immortalized by Ernest Hemingway as “The Green Hills of Africa,” form a rugged sanctuary between the Tsavo and Amboseli ecosystems. This terrain, both beautiful and punishing, presents constant challenges for wildlife monitoring.

“It’s heavily volcanic, razor-sharp lava, lots of thorny acacia trees, very steep terrain, and so it’s a very difficult area to monitor and protect,” Baird said.

This difficult environment, paradoxically, has also shielded the rhinos from heavy poaching — allowing a handful of survivors to persist where others vanished.

A Gene Pool Of Hope

The Chyulu population of eastern black rhinos is genetically distinct, a fact that makes their conservation vital. According to Royal African Safaris and the Kenya Rhino Project, these rhinos have not interbred with other populations, preserving a unique lineage that could one day strengthen the species’ genetic diversity.

Decades ago, poaching nearly erased this subspecies from existence. By the late 1990s, the Chyulu group was believed extinct until rangers discovered a hidden cluster that had quietly survived in the lava-scarred wilderness. Since then, relentless protection efforts — from aerial patrols to a network of 48 camera traps — have brought cautious optimism.

Today, the population has grown to just nine individuals, making every single calf a cause for celebration.

“For such a small population, every calf and every new birth is a really big deal and something to be celebrated,” Baird said.

This new birth follows another in late 2023, when a young rhino was born and has since begun to roam independently. Rangers have even observed its mother pairing again with a male, suggesting that a third calf may soon join the fragile herd — an extraordinary sign of continuity for a group once thought lost.