A crane towering over Malaga Cathedral, a jewel of the Spanish Renaissance, heralds a historic fulfilment. A watertight roof is being built for the first time since its construction started nearly five centuries ago. Fixing an age-old problem, the work is transforming the profile of the city’s most emblematic building.

The restoration marks a crowning moment for Malaga as the southern port city basks in a boom that mirrors Spain’s much-lauded economic success.

The cathedral project is led by Francisco de la Torre, 82, Malaga’s mayor for 25 years who is credited with putting the city on the world map.

“Malaga and Spain are experiencing their best years economically. I have no doubt,” de la Torre, from the conservative Popular Party, said.

Spain’s economy, the eurozone’s fourth-largest, has outperformed its peers since 2021, driven by tourism, low energy prices, domestic consumption and immigrant labour. The International Monetary Fund recently ranked Spain as the fastest-growing advanced economy, raising its 2025 growth forecast to 2.9 per cent after a 3.5 per cent expansion last year.

The central bank forecasts GDP growth of 2.6 per cent this year, more than double the eurozone average.

The success is in stark contrast to 2008 when the country was ravaged by a housing market collapse and a banking crisis. It is all the more notable against the backdrop of the effectively paralysed, corruption-tainted minority government of Pedro Sánchez, the Socialist prime minister, who has been unable to pass a budget since he retained power after inconclusive elections in 2023.

But as Spain looks back at its transition to democracy five decades ago, leaders such as de la Torre warn that low productivity and a new housing crisis could overshadow its success. According to the OECD, Spain’s productivity growth fell from 2.5 per cent in the 1980s to 1.2 per cent in the 2010s, and has deteriorated both in absolute terms and relative to other OECD countries from above-average in 1991 to below-average in 2021.

Housing costs have risen almost 50 per cent faster than youth wages since 2014, and the average property rental is now equal to more than 90 per cent of a young worker’s income. The Bank of Spain recently declared that the country had a shortfall of 700,000 houses.

Luis Garicano, a professor of public policy at the London School of Economics, said that living standards had “stagnated” since 2007 and the country was falling behind European averages, for example, in GDP per capita.

“The story [since Franco’s death] is one of high expectations that end in disappointment,” Garicano, a former centre-right Spanish MEP, said. “It starts with rapid convergence, not just towards Europe but also the US, but then falls behind.

“We have stagnation, the collapse of the prospects of young Spaniards who have such low salaries they can’t afford housing.”

That gloomy picture is not immediately evident in Malaga, Spain’s sixth city. Bustling and spruced up, the “empire of light”, as the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset described it in 1910, is a far cry from the shabby former industrial city of 25 years ago, when tourists bypassed it and headed straight to the Costa del Sol’s resorts.

• 50 years after Franco’s death, is Spain’s democracy in danger?

De la Torre has overseen the city’s transformation into a tourist destination itself, the growth of its tech industry and the opening of a handful of art museums, including one dedicated to Pablo Picasso, who was born in the city, and an outpost of Paris’s Pompidou Centre.

Antonio Banderas, the actor, has returned to his home town to open a theatre, and is an enthusiastic celebrant of another of Malaga’s great draws — its well-marketed Easter religious processions.

Highlighting the great change that Spain has undergone, de la Torre described the state of Malaga on Franco’s death on November 20, 1975. He said: “It was a very run-down historic centre with a feeling of abandonment, not attractive to live in. We had no tourist appeal and the world was suffering an oil crisis.”

Recalling the repressive atmosphere, he pointed to the ban on works by the renowned British hispanist Gerald Brenan, who is buried in the city’s English Cemetery. “Even though he wrote some of them in Malaga [during the dictatorship], they were forbidden,” he said. “Spain was politically and economically distant from Europe.”

Francisco de la Torre

ALEX ZEA/EUROPA PRESS/GETTY IMAGES

Franco started to open the economy, notably tourism, after his devastating autarky policy ended in 1959. But the “internationalisation” of the country’s economy after his death, particularly joining the EU and the euro, led to a massive leap in prosperity, said Raymond Torres, the director for macroeconomic analysis at Funcas, an economics think tank.

He said: “Exports of goods and services represented about 12 per cent of GDP in 1975. That has increased almost continuously to around 40 per cent of GDP today.”

Fringed with palm trees and backed by a Moorish castle, Malaga’s baroque revival city hall encapsulates the country’s romantic image. But its mayor’s career exemplifies the development of modern Spain. As an official under Franco, he was a founder of the city’s university, which is now a major partner with the technology park that he also helped to establish in 1992.

As Spain tries to diversify away from a heavy reliance on tourism, which accounts for 13 per cent of GDP, Malaga TechPark has become a centre of the country’s burgeoning industry. Built on farmland ten miles outside the city, it has attracted companies such as Accenture and Ericsson. The Belgium-based research & development giant Imec is planning a €600 million semiconductor facility in the park.

Until recently tourism had represented about 80 per cent of the city’s economy. Experts estimate that the tech industry now accounts for nearly a third. “Google’s new cybersecurity centre and Vodafone’s AI development centre in Malaga have suddenly put a relatively small Mediterranean city on the global stage,” said Felipe Romero, the park’s general manager.

The park is a source of optimism in Spain but Ezequiel Navarro, a leading tech businessman, said that the sector was underrepresented in the country’s economy. “We are still a country of users and not makers,” he said.

Torres, the think tank analyst, said that in addition to low productivity there was insufficient domestic investment to sustain growth, a lack of housing investment and a need for education reforms.

“Lots of young Spanish people leave the country because they find higher wages elsewhere,” he said. “Unemployment among tertiary education graduates is much higher than anywhere else [in Europe]. That’s really not acceptable.”

So far this year, 463,000 immigrants have entered Spain and 183,000 people have emigrated, Torres said.

The immigration debate in Spain has become embittered, notably since race riots erupted in Torre Pacheco, Murcia, after a Moroccan youth was accused of beating up an elderly man in the summer.

The bulk of an 8.2 million rise in Spain’s population between 2000 and 2024 was due to net immigration, according to the Elcano Royal Institute think tank. Without that, the rapidly ageing country might not have seen any population growth at all, the institute said.

Acknowledging the pressure that immigration was putting on the housing market, Torres said that “without immigration it would be a shrinking labour force, and therefore it would have been impossible to have growth in the tourism sector, which accounts for about 60 to 70 per cent of new jobs”. But immigration is slowing down, mainly due to the difficulty in finding housing, according to a Funcas report published last month.

Sanchez recently boasted that immigration accounted for 25 per cent of Spain’s per capita GDP and 10 per cent of its social security revenues, yet only 1 per cent of public expenditure.

But Garicano, the LSE professor, said: “The truth of the matter is that bringing unqualified immigrants in without an active policy means that anybody who earns below €30,000 contributes to the public budget less over their lifetime [than they take out of it].”

In Malaga, the silk-cotton trees are in flower, the sun is out and, in contrast to the polarised national politics, the city is blossoming under de la Torre’s consensual style of leadership.

But, as elsewhere in Spain, anger over the lack of housing and overtourism — its historic centre has about 6,000 short-let tourist flats, the highest density in Spain — is mounting.

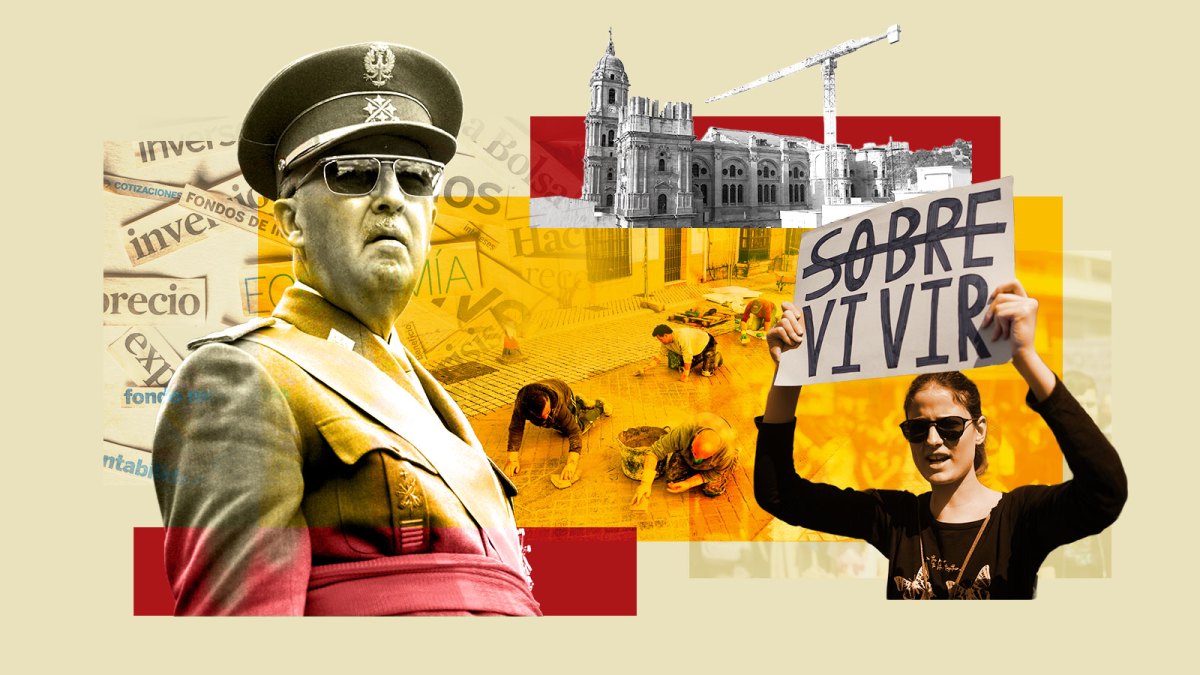

Protesters demonstrate in Malaga demanding decent and affordable housing

JESUS MERIDA/SOPA IMAGES/LIGHTROCKET/GETTY IMAGES

Juan Luis Frias, 60, a taxi driver, welcomed the return of business to Malaga and acknowledged that tourism was an essential income source.

“But renting or buying has become a luxury,” he said. “We are losing the city centre to tourism. If three cruise ships come into port, 12,000 passengers congest the streets. They have to manage it better.”

Soon tourists will be able to conquer another piece of Malaga. When the cathedral restoration is completed within the next few years, visitors will be able to amble among the rafters of its new roof.

The mayor quipped that he may not be around to resolve the building’s last major outstanding job: the city continues to debate whether to build the second tower, which was never completed and earned the building its nickname La Manquita, “the one-armed lady”.

The cathedral is slowly nearing the end to its finishing touches

ALAMY

For some, like Garicano, Spain’s economy, similarly, is an unfinished work. Even though unemployment has fallen to levels not seen since 2008, almost 2.5 million people are still out of work in a country with a working-age population of nearly 25 million.

Data published by the Foessa Foundation suggests that 26 per cent of Spaniards live below the poverty line and 8 per cent live in severe poverty.

“So we had the transition to democracy after Franco’s death, the opening up, and the optimism, and then the housing boom and crash and here we are back where we started, but no longer making the reforms and investments,” Garicano said. “We have failed to converge with other modern states and become a grown-up economy.”