Researchers have long faced a blunt limitation in biology. They could delete proteins or switch genes off, but they could not finely tune how much of a protein existed in specific tissues over an animal’s lifetime.

That gap has slowed progress in understanding ageing and how organs influence one another at the molecular level.

Now, scientists have developed a method that allows precise, lifelong control of protein levels inside different tissues of a living animal.

The technique lets researchers increase or decrease proteins with calibration rather than force.

It opens new ways to study ageing, disease, and whole-body biological coordination.

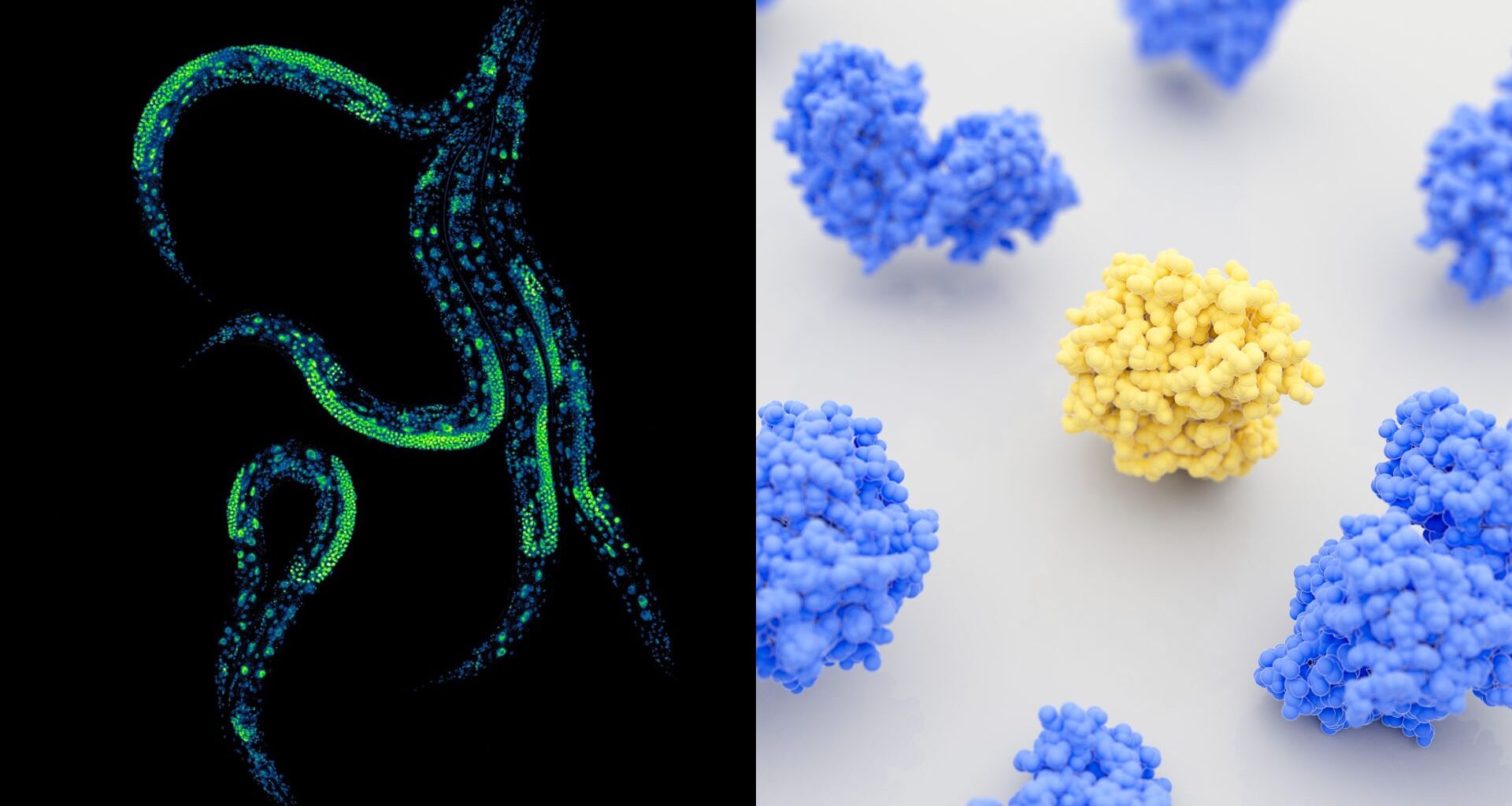

Scientists at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and the University of Cambridge demonstrated the approach in the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans.

They adjusted protein levels in the animals’ intestines and neurons while the worms continued to live, eat, and grow normally.

The new method addresses a long-standing challenge in experimental biology.

Many existing tools remove proteins entirely or work only for short periods. Others fail to target specific tissues over an animal’s full lifespan.

These limits have made it difficult to study systemic processes like ageing. Ageing depends on constant communication between organs.

A protein may extend lifespan in one tissue but shorten it in another. Standard on-off genetic experiments often cannot separate these effects.

“No protein acts alone. Our new approach lets us study how multiple proteins in different tissues cooperate to control how the body functions and ages,” says Dr. Nicholas Stroustrup, researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation and senior author of the paper.

Researchers have also struggled to track how small molecular changes spread across the body over time.

Subtle shifts in protein levels can have outsized effects, but older tools lack the precision to measure them.

Turning proteins like volume

“To unpick nuance in biology, sometimes you need half the concentration of a protein here and a quarter there, but all we’ve had up till now are techniques focused on wiping a protein out,” explains Dr. Stroustrup.

“We wanted to be able to control proteins like you turn the volume up or down on a TV, and now we can now ask all sorts of new questions.”

The technique builds on a system originally developed from plant biology. Plants use a hormone called auxin to regulate growth. Scientists adapted this process into the auxin-inducible degron, or AID, system.

In the AID system, researchers tag a protein with a degron. An enzyme called TIR1 recognizes the tag and destroys the protein when auxin is present. When auxin disappears, the protein returns. Scientists widely use this system for rapid, reversible protein control.

However, the classic AID system mostly works like a switch. Proteins appear or disappear, with little control over dosage or location.

Dual-channel breakthrough

The research team engineered a more flexible version called a “dual-channel” AID system.

They created different versions of the TIR1 enzyme and matching degron tags. Each enzyme responds to a different auxin compound.

By placing these enzymes in different tissues, the scientists independently controlled the same protein in neurons and intestines.

They also controlled two different proteins at the same time. The team tested the system across more than 100,000 worms.

The researchers also solved a major hurdle.

Many AID systems fail in reproductive tissues. The team traced the issue to a biological process in the germline and modified their system to overcome it.

“Getting this to work was quite an engineering challenge. We had to test different combinations of synthetic switches to find the perfect pair that didn’t interfere with one another,” says Dr. Jeremy Vicencio, postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation and coauthor of the study.

“Now that we’ve cracked it, we can control two separate proteins simultaneously with incredible precision.”

The researchers say the tool could reshape studies of ageing and disease.

It allows scientists to ask how much protein is enough, when changes matter most, and how effects ripple across the body over time.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.