Understanding how birds learned to fly has fascinated scientists for decades. Feathers, wings, and flight are often seen as a straight line of progress from dinosaurs to modern birds.

But new research suggests the story was not that simple. Some dinosaurs may have developed the ability to fly, only to lose it later in their evolutionary history.

A recent study of rare feathered dinosaur fossils offers fresh insight into just how complex the evolution of flight really was.

Some dinosaurs lost flight

The study was led by Dr. Yosef Kiat at the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University.

The team examined dinosaur fossils preserved with their feathers and found that some of these animals had lost the ability to fly.

According to the researchers, this is an extremely rare discovery. It provides a window into the lives of creatures that lived around 160 million years ago and helps scientists better understand how flight evolved in dinosaurs and birds.

“This finding has broad significance, as it suggests that the development of flight throughout the evolution of dinosaurs and birds was far more complex than previously believed,” the research team noted.

“In fact, certain species may have developed basic flight abilities and then lost them later in their evolution.”

Brief history of feathers and flight

Dr. Kiat noted that the dinosaur lineage split from other reptiles 240 million years ago.

“Soon afterwards (on an evolutionary timescale) many dinosaurs developed feathers – a unique lightweight and strong organic structure, made of protein and used mainly for flight and for preserving body temperature.”

Later, around 175 million years ago, a group of feathered dinosaurs called Pennaraptora emerged.

These animals are considered the distant ancestors of modern birds and were the only dinosaur lineage to survive the mass extinction that ended the age of dinosaurs about 66 million years ago.

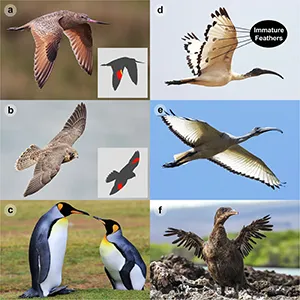

“As far as we know, the Pennaraptora group developed feathers for flight,” said Dr. Kiat. “But it is possible that when environmental conditions changed, some of these dinosaurs lost their flight ability – just like the ostriches and penguins of today.”

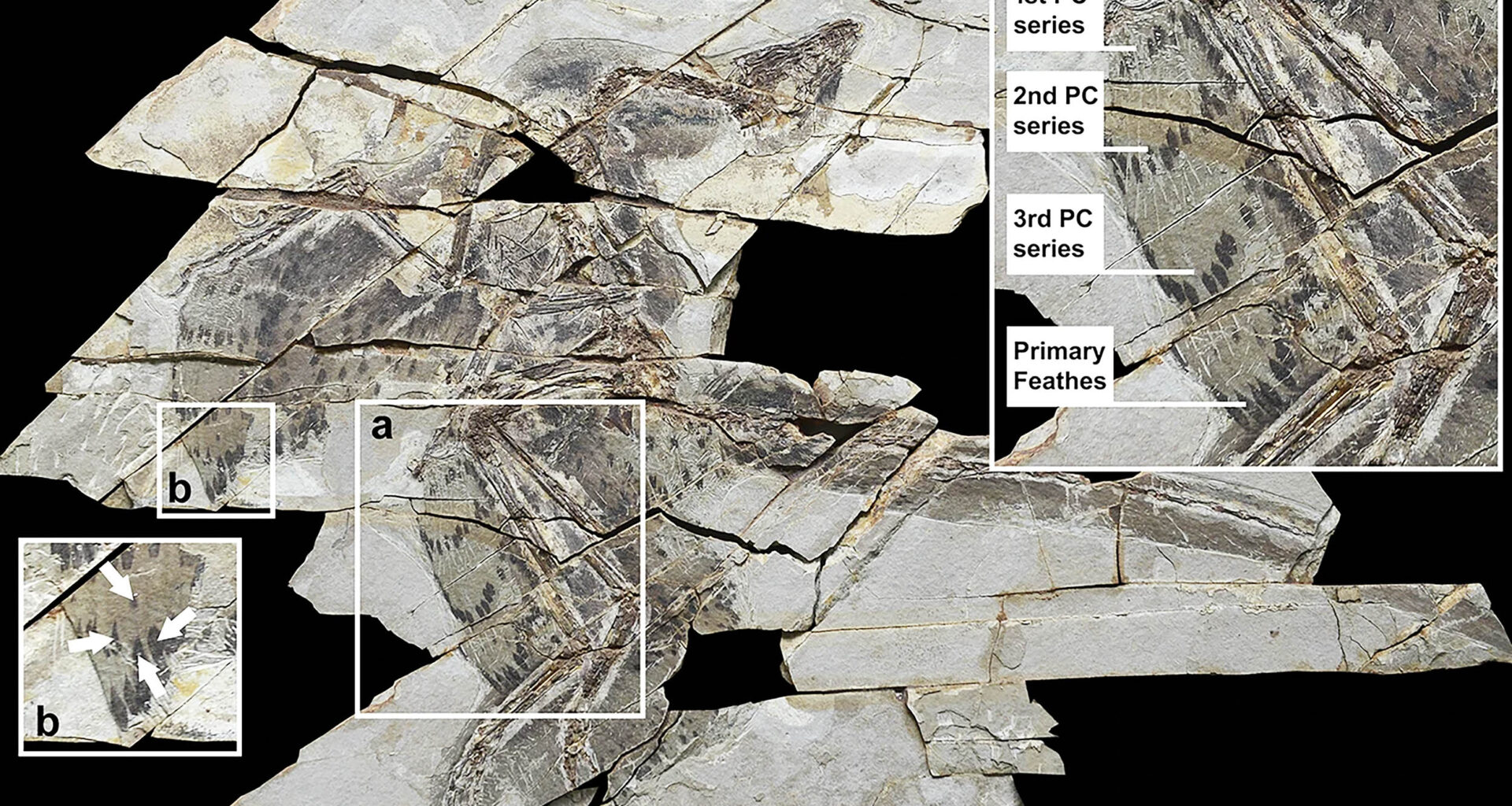

Wing morphology of Anchiornis huxleyi and the evolution of molt strategies in paravian dinosaurs. Credit: Communications Biology. Click image to enlarge.The fossils from China

Wing morphology of Anchiornis huxleyi and the evolution of molt strategies in paravian dinosaurs. Credit: Communications Biology. Click image to enlarge.The fossils from China

The research focused on nine fossils found in eastern China. All belonged to a feathered Pennaraptoran dinosaur known as Anchiornis.

Fossils with preserved feathers are extremely rare, but this region offered special conditions that allowed feathers to fossilize in remarkable detail.

What made these nine fossils especially valuable was that they still showed the original color of the wing feathers.

The feathers were white with a black spot at the tip. This detail turned out to be key to understanding how these dinosaurs lived.

Why molting matters

To understand what the feathers revealed, it helps to know how feathers grow and fall out.

“Feathers grow for two to three weeks,” said Dr. Kiat. “Reaching their final size, they detach from the blood vessels that fed them during growth and become dead material.”

“Worn over time, they are shed and replaced by new feathers – in a process called molting, which tells an important story.”

In birds that rely on flight, molting happens in a careful and balanced way so they can keep flying. In birds that do not fly, molting tends to be uneven and less organized.

The molting pattern reveals whether a winged creature was capable of flight.

Dinosaur feathers show loss of flight

The preserved feather colors allowed researchers to map the structure of the wings. They noticed a neat line of black spots along the edge of the wing.

The experts also spotted newer feathers that were still growing, because their black spots did not line up with the rest.

When the team closely examined these growing feathers, they found that molting was not happening in an orderly pattern. This strongly suggested that Anchiornis did not depend on flight.

“Based on my familiarity with modern birds, I identified a molting pattern indicating that these dinosaurs were probably flightless,” said Dr. Kiat.

“This is a rare and especially exciting finding: the preserved coloration of the feathers gave us a unique opportunity to identify a functional trait of these ancient creatures, not only the body structure preserved in fossils of skeletons and bones.”

This fossil exhibits nearly complete wings and preservation of feather coloration, allowing for a detailed identification of wing morphology. The wings have four dark bars, formed by dark spots at the tips of the feathers attached to the manus (a). Credit: Communications Biology. Click image to enlarge.Rethinking the origins of flight

This fossil exhibits nearly complete wings and preservation of feather coloration, allowing for a detailed identification of wing morphology. The wings have four dark bars, formed by dark spots at the tips of the feathers attached to the manus (a). Credit: Communications Biology. Click image to enlarge.Rethinking the origins of flight

The study adds Anchiornis to a growing list of feathered dinosaurs that could not fly. This challenges the idea that feathers always evolved for flight and stayed that way.

Feather molting may seem like a minor technical detail, but when preserved in fossils it can overturn long-held ideas about how flight began.

In the case of Anchiornis, molting patterns place it among feathered dinosaurs that could not fly, underscoring just how complex and varied the early evolution of wings really was.

This research reminds us that evolution does not always move in a straight line. Sometimes, even the smallest details can rewrite an entire story written in stone and feathers.

The study is published in the journal Communications Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–