Two of NASA’s longest-running space missions, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, have detected a searing-hot region of space where the Sun’s influence ends and interstellar space begins. The probes, launched in 1977, identified this boundary zone at the edge of the heliosphere where temperatures spike to an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 kelvin.

The region lies beyond the orbit of Pluto, in a transitional zone called the heliosheath, where the solar wind slows and interacts with the interstellar medium. Data gathered by the Voyager spacecraft suggest this zone forms a thermal barrier at the edge of the solar system, far hotter than the space within the Sun’s magnetic reach.

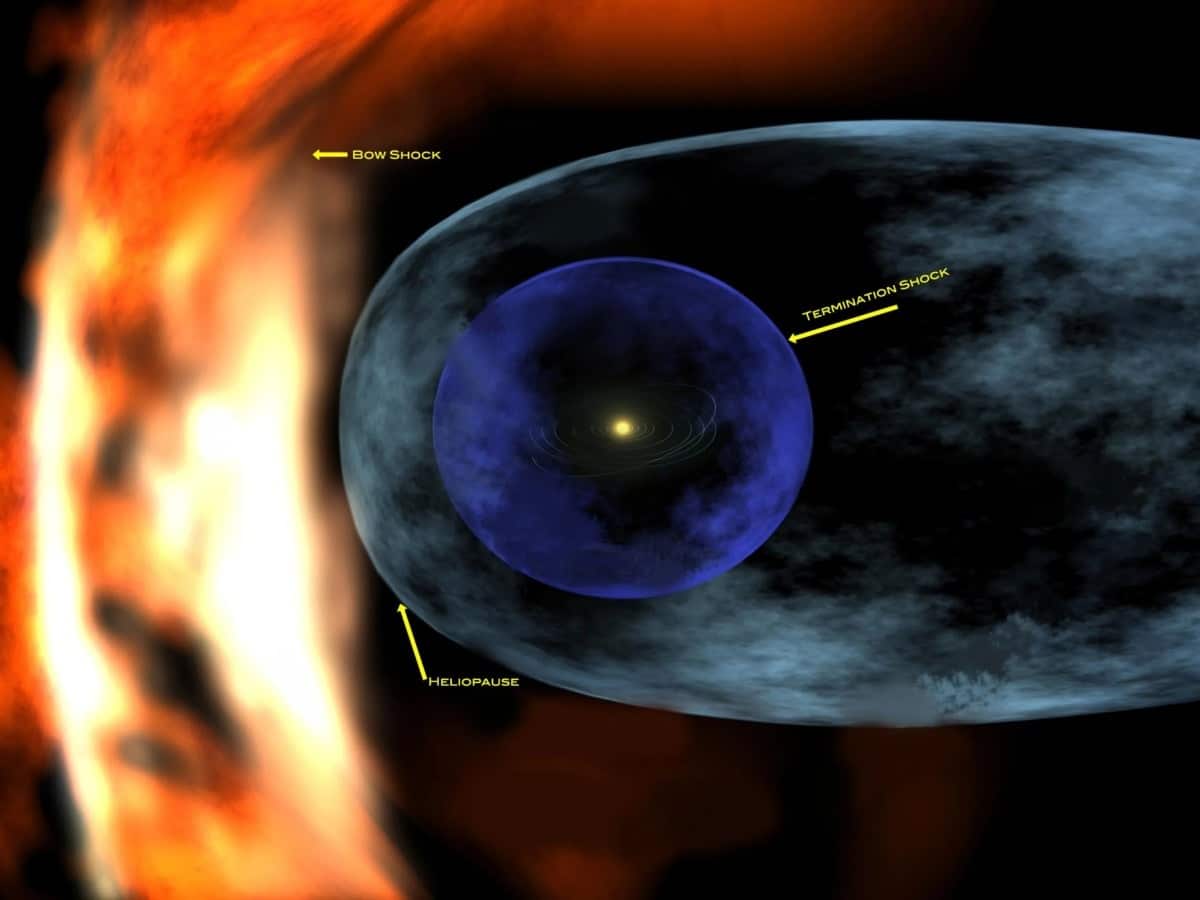

The Sun sends out a constant flow of solar material called the solar wind, which creates a bubble around the planets called the heliosphere. Credit: NASA

The Sun sends out a constant flow of solar material called the solar wind, which creates a bubble around the planets called the heliosphere. Credit: NASA

These findings revise the current understanding of how the solar system interfaces with the galaxy. Although often referred to informally as a “wall of fire,” the structure is not a solid object but a region of energetic plasma where particle behaviour and magnetic dynamics shift rapidly.

A Thermal Shock in Deep Space

Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause on 25 August 2012, becoming the first spacecraft to leave the heliosphere. Voyager 2 followed on 5 November 2018. As each passed through this boundary, mission teams recorded a sharp drop in solar particles and a corresponding rise in high-energy cosmic rays, a clear signal of entry into interstellar space.

Both spacecraft also measured significant increases in local plasma temperatures. These temperatures, although extreme in magnitude, were recorded in a region with ultra-low particle density. This means the plasma is high-energy but does not transfer heat effectively, allowing the spacecraft to remain undamaged.

This is an artist’s concept of our Heliosphere as it travels through our galaxy with the major features labeled: Termination Shock.

This is an artist’s concept of our Heliosphere as it travels through our galaxy with the major features labeled: Termination Shock.

In a NASA summary, officials confirmed that the extreme energy recorded at the boundary does not threaten the probes due to the near-vacuum conditions. The heat results from plasma particles moving at high velocities, rather than from dense collisions.

The heliopause marks the balance point where the outward pressure of the solar wind is countered by the inward pressure of the interstellar medium. The space just beyond this boundary, where the temperature jump occurs, lies within what NASA classifies as interstellar space.

Unexpected Alignment and Boundary Leakage

In addition to the temperature rise, both Voyager spacecraft provided magnetic field data that surprised scientists. Magnetic field lines inside the heliosphere were found to align with those in the region just outside. This result, observed first by Voyager 1 and later confirmed by Voyager 2, challenges earlier assumptions that the interstellar magnetic field would differ significantly in direction.

According to a 2019 NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory report, Voyager 2’s instruments also detected a leakage of particles through the heliopause. While the heliosphere functions as a partial shield against galactic cosmic rays, its outer boundary appears to be permeable. Voyager 2, which crossed the heliopause at a different position than Voyager 1, found that this flank region allows more particles to escape or enter.

This Illustration Shows The Position Of Nasa’s Voyager 1 And Voyager 2 Probes, Outside Of The Heliosphere, A Protective Bubble Created By The Sun That Extends Well Past The Orbit Of Pluto. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This Illustration Shows The Position Of Nasa’s Voyager 1 And Voyager 2 Probes, Outside Of The Heliosphere, A Protective Bubble Created By The Sun That Extends Well Past The Orbit Of Pluto. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Both spacecraft also recorded increased plasma density before and after the boundary crossing, suggesting compression on either side of the heliopause. The higher-than-expected density may indicate that interstellar pressure is shaping the outer layers of the heliosphere more actively than previously modelled.

Defining the Solar System’s Outer Limit

The heliosphere is formed by the continuous flow of solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the Sun. This flow travels well beyond the orbits of the planets before slowing in response to the interstellar medium. The transition begins at the termination shock, where the solar wind decelerates abruptly. Beyond this lies the heliosheath, a turbulent layer leading to the heliopause.

NASA defines the heliopause as the official boundary between solar space and the interstellar environment. The position of this boundary is not fixed. It shifts with changes in the Sun’s activity cycle, which repeats approximately every 11 years. This variability explains why the Voyager probes encountered the heliopause at different distances from the Sun—about 121 AU for Voyager 1 and around 119 AU for Voyager 2.

The space beyond the heliopause contains colder, denser plasma that originates from past supernovae. Both spacecraft recorded an abrupt change in particle composition and temperature, consistent with leaving the Sun’s protective influence.

NASA’s heliophysics division continues to use data from the Voyager mission to refine models of how the Sun’s magnetic and particle fields behave on galactic scales. Other missions, including the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) and MAVEN, also contribute to this broader research effort.