Over time, hematopoietic or blood stem cells can quietly acquire mutations that push them to divide just a little more aggressively, creating a larger group of clones in the bone marrow. In a fraction of people with this phenomenon, called clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential — CHIP, for short — these cells can transform into cancers such as leukemia, though most will remain benign.

One possible reason for this variability might lie in a genetic variant that appears to protect against the development of CHIP and its progression into certain blood cancers, according to a study published on Thursday in Science. The work also reveals a potential avenue to develop new therapeutics for the pre-cancerous condition, something that cancer researchers have sought for years.

Having the genetic variant “reduced your risk of myeloid malignancies by 20%,” said Vijay Sankaran, the senior author on the study and a physician-scientist at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Broad Institute. “What we’re excited about here is we identify a pathway that’s critical for this progression, and could be targeted.”

STAT Plus: ‘Remarkable’ drug results against an aggressive leukemia

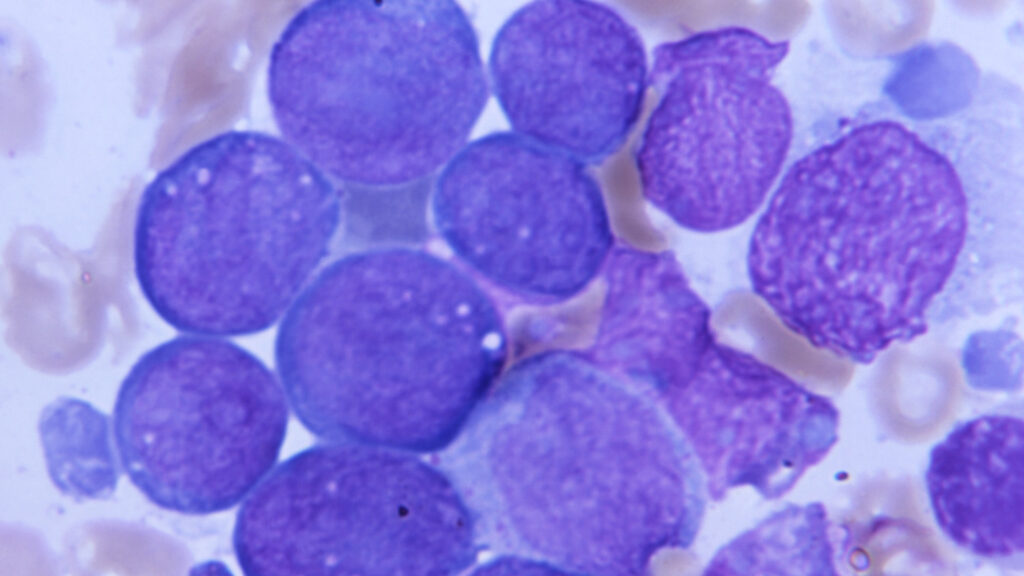

Adults have tens to hundreds of thousands of hematopoietic stem cells. They are the initial source for our blood, including red blood cells, platelets, and most immune cells, and also must renew themselves. As these cells replicate, CHIP can occur when they pick up mutations commonly associated with certain blood cancers. Alone, it’s not enough to transform them into cancer, but it can push them to multiply faster — creating a group of clones that disproportionately contribute to blood production.

These mutant cells produce blood just as well as their nonmutant brethren, but they progress into cancers like leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome at a rate of about 1% per year. CHIP is also associated with worse outcomes across a range of conditions including cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

“With some rare exceptions, CHIP has been bad all around,” Sankaran said. “We know, in general your risk of blood cancer is increased three to five times compared to the general population.”

Sankaran wanted to find genetic variations in people that might predispose them towards getting CHIP or potentially protect them from it. To do the study, he began looking in large biological databases like the UK Biobank and from the All Of Us Study and studying the genomes of people with and without CHIP mutations. In the team’s analyses, the researchers found that people who had a specific genetic variant that lowers levels of a protein called Musashi2, or MSI2, seemed to be less likely to develop myeloid cancers.

“If they have one copy of this variant, they’re far less likely to show expansion of those CHIP clones. You are 1.8-fold more likely for that clone to disappear,” Sankaran said.

The protein’s normal function is to bind mRNA in the cell, stabilizing it and allowing the cell to construct more of the protein encoded within the mRNA. In subsequent analyses, Sankaran found that some of these mRNAs tend to derive from genes related to cell growth and, when mutated, are linked to cancers. Lowering MSI2 in the hematopoietic stem cells thus might also dampen the impact of overactive growth, Sankaran hypothesized.

“This is probably like putting the brakes on the self-renewal that cancers take advantage of,” he said.

Identifying a protective variant like this is “groundbreaking,” said Koichi Takahashi, an oncologist and cancer researcher at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who did not work on the study. “The finding that this particular inherited variant will protect you from getting CHIP and also myeloid malignancy, this can be translated to precision oncology,” he said.

Elucidating how the MSI2 protein might affect cancer development creates a potential research path toward developing preventive medicines for blood cancer. “There’s no good way currently to downregulate Musashi2 but, if there is a way, it could be applied as a therapeutic option,” Takahashi said.

Though, he added, it will take significant work to develop such a therapeutic, including understanding whether there are any drawbacks to modifying MSI2 levels in this way. “They reported in this paper that individuals with this variant, yes, it reduces risk of CHIP and myeloid malignancies, but at the same time, these individuals have lower blood counts overall,” Takahashi said. Theoretical concerns include an increased risk of bleeding or infection.

Still, some individuals with CHIP have a significantly higher risk of developing blood cancers than others, including people with high risk mutations like TP53 or with large CHIP clones. In some high-risk cases, the chance of developing blood cancer over the next 5 to 10 years can be as high as 60%, Takahashi said. “If treatment can really reduce or abolish risk of getting myeloid malignancy, then maybe a mild level of toxicity can be acceptable,” he said.

That’s where Sankaran hopes this research will go eventually. “The field has advanced so much in knowing how to detect CHIP and what some risks associated with CHIP are,” he said. But the field has not yet figured out what to do once CHIP is found. Perhaps, he said, research on MSI2 can finally lead to a therapeutic option for high risk patients where there hasn’t been one.