By manipulating individual atoms in molten metal, the scientists managed to hold the liquid in place, preventing it from crystallizing even at temperatures far below its normal freezing point.

The discovery stems from experiments on metallic nano-droplets placed on atomically thin graphene, where researchers observed the formation of a “hybrid” phase of matter. This new form could significantly alter how we understand material properties at the atomic level, and may lead to future advancements in energy storage, conversion, and nanotechnology applications.

Modern technology increasingly relies on the efficient use of rare earth and precious metals like platinum, gold, and palladium, especially in fields like clean energy and catalysis. The behavior of metals during their transition from liquid to solid, called the solidification pathway, has a major influence on their performance. While most studies treat these transformations as predictable, the new findings show that atomic behavior in supercooled liquids can defy standard models.

Liquid Atoms, Frozen In Place

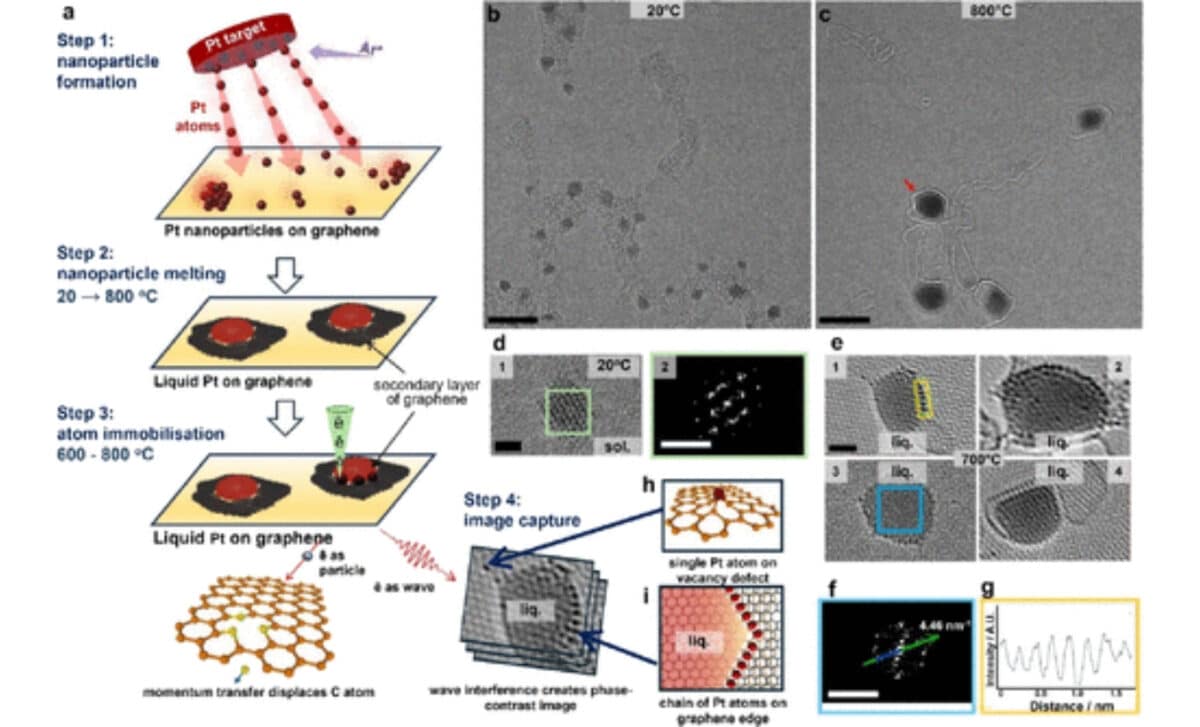

The researchers carried out their observations using the Sub-Angstrom Low-Voltage Electron (SALVE) microscope, an advanced transmission electron microscope located at the University of Ulm. This tool allowed them to monitor the melting and solidification of metal nanoparticles at ultra-high resolution in real time.

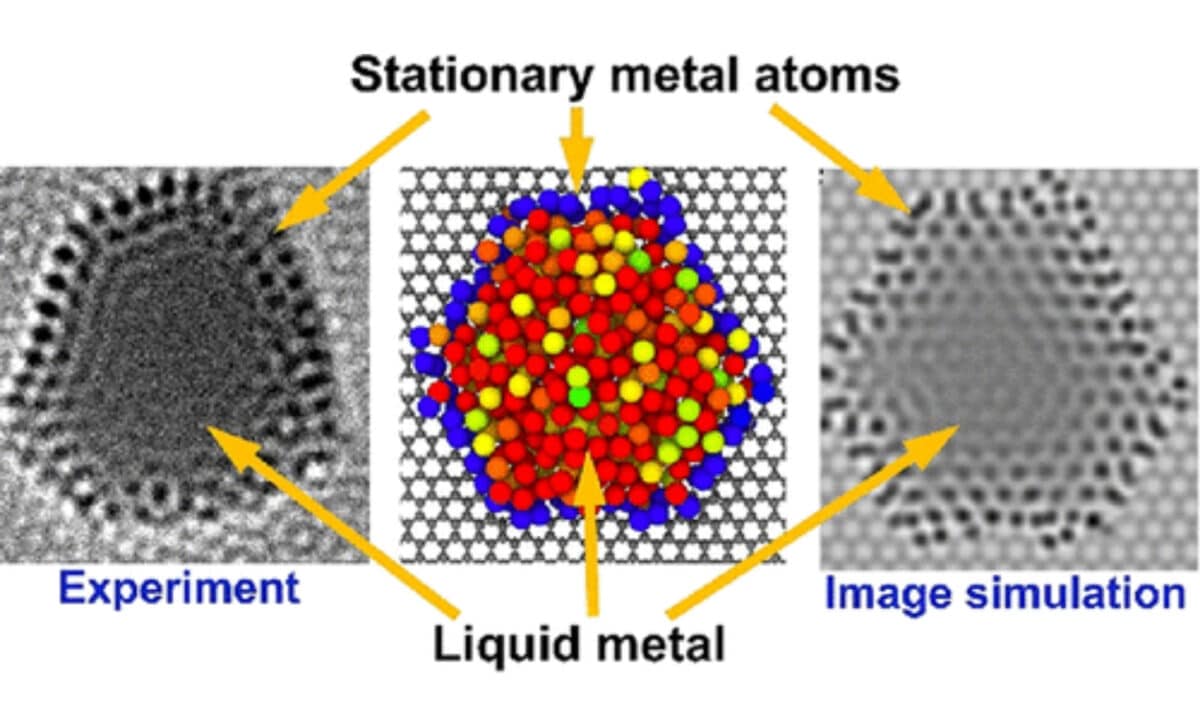

According to the team, the process began by melting nanoparticles of platinum, gold, and palladium on a thin graphene surface. The heat caused most atoms to move and vibrate as expected, but some remained still. “We began by melting metal nanoparticles, such as platinum, gold, and palladium, deposited on an atomically thin support, graphene,” explained Christopher Leist, co-author of the study published in ACS Nano. “We used graphene as a sort of hob for this process to heat the particles, and as they melted, their atoms began to move rapidly, as expected. However, to our surprise, we found that some atoms remained stationary.”

These motionless atoms were not random. They became bonded to point defects in the support material. This anchoring effect was the key to producing what researchers began calling atomic corrals, circular regions where the atoms at the boundary remained fixed while the inner atoms remained in a liquid state.

The Atomic Corral Effect

By carefully increasing the number of defects in the graphene using a controlled electron beam, scientists discovered they could create more stationary atoms, which gave them greater control over the behavior of the liquid metal. The denser the network of defects, the more atoms stayed fixed in place.

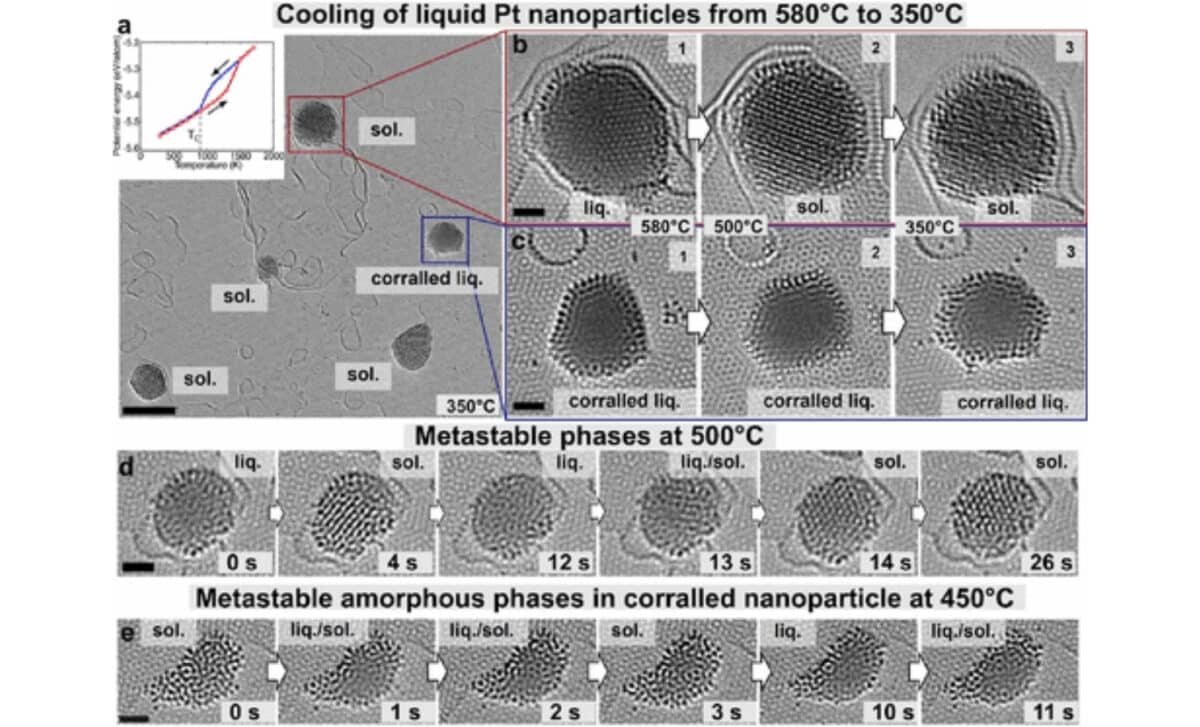

This allowed the researchers to form rings, true “corrals”, that trapped liquid atoms inside. Once the metal was encircled by these stationary atoms, something remarkable happened. Even after lowering the temperature well below the normal freezing point, the liquid inside the corral did not crystallize.

“Once the liquid is trapped in this atomic corral, it can remain in a liquid state even at temperatures significantly below its freezing point, which for platinum can be as low as 350 degrees Celsius, that is more than 1,000 degrees below what is typically expected,” said Andrei Khlobystov, co-author from the University of Nottingham. The effect only lasted as long as the ring remained intact. If the corral was disrupted, the liquid would begin to solidify, but not into a normal structure.

A Short-lived But Revealing Hybrid Phase

The trapped liquid didn’t transition into a regular crystalline lattice, which is how metals usually solidify. Instead, it first formed an amorphous solid, a highly unstable structure lacking long-range order. Only after the ring of stationary atoms was broken did the amorphous form give way to a typical crystalline solid.

This behavior introduces a hybrid state of matter, combining properties of both liquids and solids. According to the study, the stationary atoms change the rules of solidification, allowing for temporary but measurable control over the state of the material. That control could have practical applications.

As reported by Popular Mechanics, the findings could eventually contribute to clean energy conversion and storage, as well as improve the performance of platinum-on-carbon catalysts, which are widely used in fuel cells. These materials depend heavily on how metals crystallize and interact at the nanoscale.