Germany is heading for significant job losses and a “massive” rise in old age poverty unless it can curb the runaway costs of its pensions system, according to one of the government’s economic advisers.

The ruling coalition is locked in a tetchy dispute about the scale of the welfare state after the finance ministry identified a €172 billion hole in its spending plans for the rest of the decade.

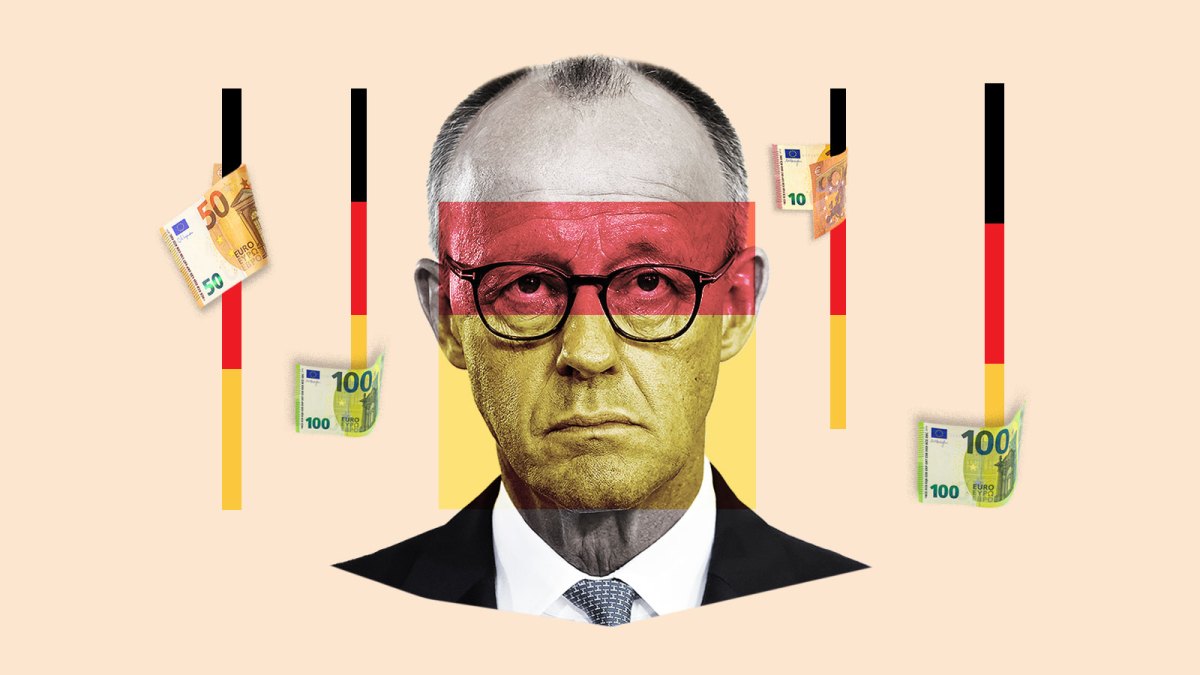

Friedrich Merz, the conservative chancellor, caused uproar when he declared that the country had been “living beyond its means for years” and could no longer afford the costs of the system, which have increased to more than 31 per cent of GDP, one of the highest levels in Europe.

Merz warned of a “profound epochal break” and the need for “painful” austerity measures to ensure that younger Germans would have any hope of future prosperity.

Bärbel Bas, his Social Democratic Party labour and social affairs minister, publicly dismissed the chancellor’s speech as “bullshit”.

In a speech on Tuesday, President Steinmeier, a fellow Social Democrat, hailed the welfare state as a “treasure” and a “resource that has made our country what it is’. However, he acknowledged that the “system is creaking” and in dire need of modernisation.

The coalition partners are now wrangling over what is billed as an ambitious “autumn of reforms” to the economy, with the Bürgergeld — basic unemployment benefit — first in the firing line.

• Friedrich Merz’s trillion-euro gamble with the German economy

However, Marcel Fratzscher, head of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) and an adviser to the economics ministry, said the most pressing task was to rein in a public pensions bill that has reached more than €400 billion a year and is projected to rise substantially in the decade to come.

Marcel Fratzschern said: “The first worst-case scenario is that this burden of contributions leads to a severe weakening in the economy and the loss of many good jobs,”

BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/ALAMY

Last week the ministry published a white paper by four other economists that described the “dysfunctional” pensions system as “social dynamite” and a “grave” threat to the economy.

It cited forecasts that by the middle of the next decade there will be one pensioner for every two people of working age. By 2070, when today’s youngest Generation Z workers would notionally be entering retirement, the ratio is forecast to be one to one.

The document also said that the average 65-year-old in Germany today could expect to live for another 22 years, up from fewer than 18 in 1990 and fewer than 14 in 1950.

Katherina Reiche, the economics minister, said the analysis pointed to a “profound and urgent need for reform” to ensure that the country could afford its pensions.

Unlike in Britain, the German system is supposed to be financed through workers’ and employers’ contributions to a national pension insurance system that guarantees the average pensioner will receive 48 per cent of their previous salary.

• Why is Germany’s economy in such a poor state?

Yet the money coming in cannot keep pace with the pensions payments that are going out, meaning the taxpayer will chip in an additional €121 billion this year to make up for the shortfall. That figure is about 3 per cent of GDP, or significantly more than the current annual defence budget.

At the same time, the contributions to the pensions, health, old age care and other social insurance funds — which are split evenly between the worker and their employer — have reached 43 per cent of the average person’s salary and are expected to approach 46 per cent at the end of this decade.

“The first worst-case scenario is that this burden of contributions leads to a severe weakening in the economy and the loss of many good jobs,” Fratzscher said. “The second is a massive increase in old-age poverty.”

A recent poll for the public broadcaster ZDF suggested that 94 per cent of Germans feared the pensions system would face serious problems but 72 per cent had no confidence in the government to fix them.

One suggestion is that better paid workers retire later

CHRISTOPH STEITZ/REUTERS

Fratzscher, who is also professor of macroeconomics at the Humboldt University of Berlin, said that younger generations are already buckling under the financial weight placed on their shoulders.

In his latest book, After Us, the Future, he wrote: “Since the age of Enlightenment and the industrial revolution, hardly any other generation has robbed its children and grandchildren of so many chances for a good and self-determined life as the baby boomers are doing today.”

Fratzscher’s proposals for a new “social contract” between the generations have upset many on the right. They include a “boomer solidarity tax” under which the richest 20 per cent of baby boomer households would pay an additional levy amounting to 3 or 4 per cent of their retirement income, which would subsidise poorer pensioners at no additional cost to the workforce.

The economist has also made the case for forcing baby boomers, roughly those born in the two decades after the end of the Second World War, to do a year of social service.

An obligatory spell of caring for the elderly, minding small children or similar work immediately after retirement would, Fratzscher suggests, be a “small step to bring a bit more balance back to the solidarity in our society”.

“People don’t want to understand problems that they can’t see or directly feel,” he said. “There is a certain denial of reality and often that means politicians will put off reforms until they can no longer be avoided, but at that point they are maximally painful.”

He added: “The dilemma is further exacerbated by the fact that for the parties in the current government … their main voter base is older people, the over-fifties or even the over-sixties.

“So in principle they would have to act against the interests and explicit wishes of their own electoral constituencies, and that’s what makes it so tricky to implement reforms.”

One economist fears there will be a big increase in poverty among the elderly

JAN TEPASS/GETTY IMAGES

The economics ministry is now flirting with the idea of automatically linking the retirement age to life expectancy. In Denmark, this mechanism recently compelled the government to phase in an increase from 67 today to 70 by 2040.

In Germany, however, sporadic proposals to lift the standard age threshold, which is just over 66 but due to be frozen at 67 in 2031, have been unanimously rejected by political parties.

Fratzscher proposed that the retirement age be staggered according to hourly wages, so that better-paid people would start drawing their pension later while lower earners, who are more likely to do physically demanding jobs, would do so earlier.