It was purely by chance that a NASA team stumbled upon a long-lost American military base buried deep beneath Greenland’s ice. Hidden for more than sixty years, its remains were rediscovered thanks to an experimental airborne radar designed to map layers of frozen terrain.

Back in 1959, the U.S. Army built a secret base under Greenland’s ice sheet. Officially presented as a scientific research project, Camp Century was in reality a Cold War initiative meant to position American nuclear missiles closer to Soviet territory. Up to six hundred warheads were planned to sit in silos beneath the ice — though none ever did. By 1964, melting ice was already threatening to destroy the base’s 21 tunnels, forcing its abandonment. The project remained classified until 1997 and, despite occasional monitoring, had largely faded into obscurity — until now.

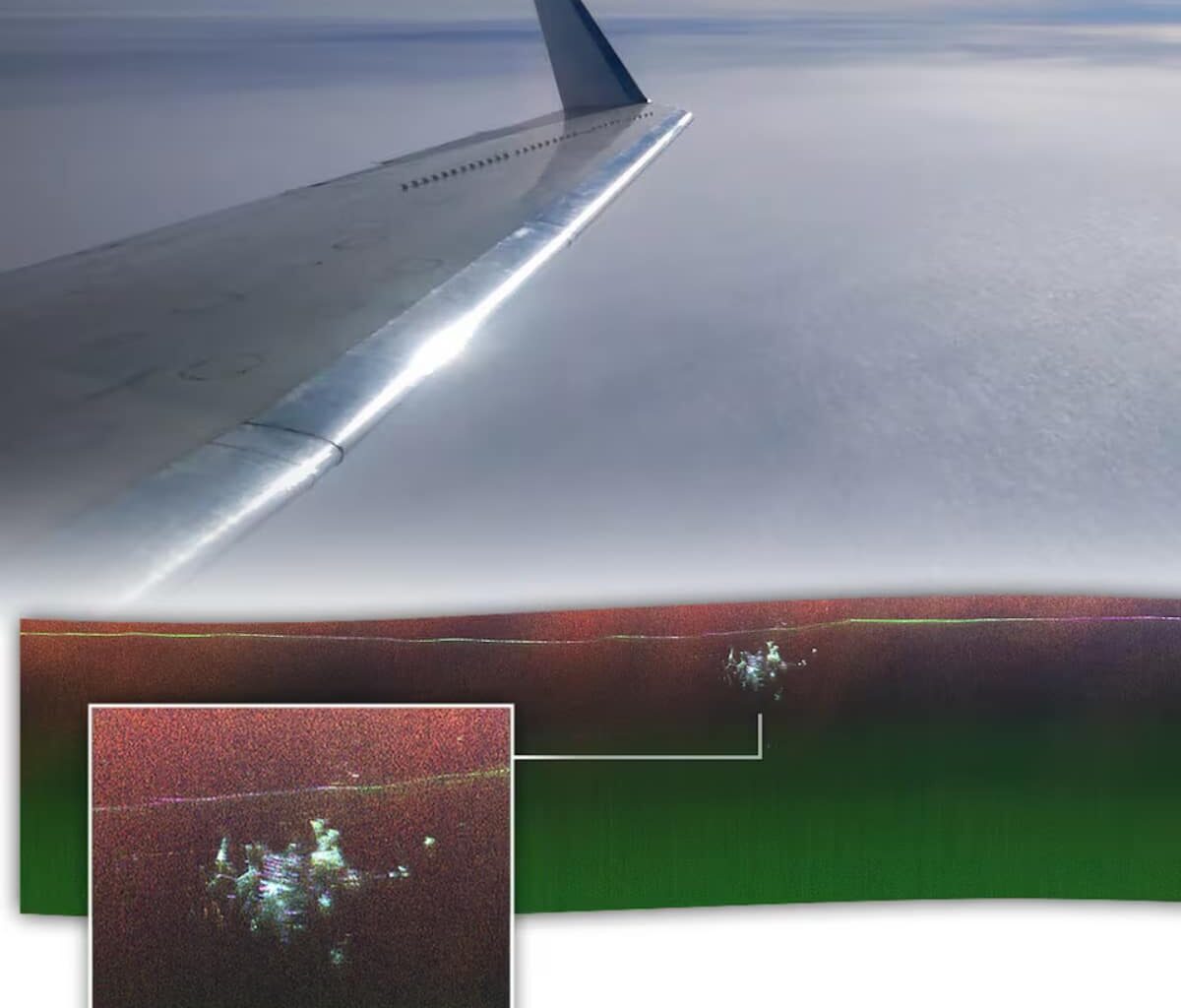

In April of this year, a NASA crew flew over northwestern Greenland aboard a Gulfstream III to test a new radar capable of spatial mapping. Engineers were using the system to chart the multiple layers of the ice sheet down to its bedrock. Originally designed for Antarctica, the radar will help scientists measure the thickness of ice sheets and forecast future sea-level rise. But during the test flight, it detected a buried mass beneath the ice — the legendary Camp Century, once dubbed the “city under the ice.” At first, the team didn’t realize what they had found.

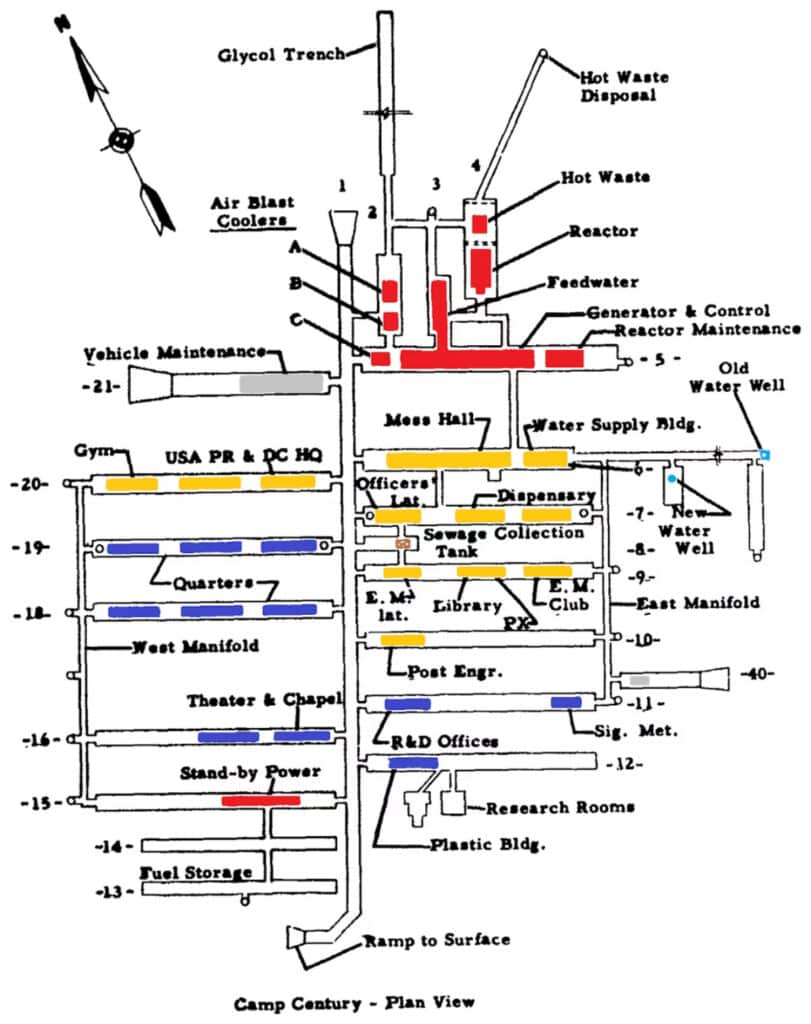

Map of Camp Century, also known as “the city under the ice.” At the top, you can see the structures that powered the camp using a mini nuclear reactor. The tunnels provided access to various living and working areas. Originally intended to house nuclear missiles, the base was ultimately used to extract the first ice cores to study climate evolution over 100,000 years. © Campcentury.org

A hidden pollution threat?

This Cold War base, once believed to be on the verge of reemerging due to global warming, still lies about 100 feet below the surface. The radar test, however, managed to produce a visual map of the structure’s remnants. Ground-penetrating radar works by sending radio waves into the ground and measuring how long they take to bounce back. The system can also reveal inner ice layers and the rock foundation beneath, creating a precise 2D image of what lies below.

NASA’s new radar takes it a step further — capturing data from multiple angles to produce a full 3D reconstruction. When researchers compared the new radar map with Camp Century’s original plans, they could pinpoint the tunnels and key installations. The camp once functioned as a miniature city, complete with a hospital, theatre, church, and shop. Its power, heating, and water came from a small nuclear reactor. Now, the rediscovery raises serious environmental concerns: when melting ice eventually exposes the base, all its buried chemical, biological, and radioactive waste could resurface — unless the entire structure sinks deeper into Greenland’s icy depths instead.

Sylvain Biget

Journalist

From journalism to tech expertise

Sylvain Biget is a journalist driven by a fascination for technological progress and the digital world’s impact on society. A graduate of the École Supérieure de Journalisme de Paris, he quickly steered his career toward media outlets specializing in high-tech. Holder of a private-pilot licence and certified professional drone operator, he blends his passion for aviation with deep expertise in tech reporting.

A key member of Futura’s editorial team

As a technology journalist and editor at Futura, Sylvain covers a wide spectrum of topics—cybersecurity, the rise of electric vehicles, drones, space science and emerging technologies. Every day he strives to keep Futura’s readers up to date on current tech developments and to explore the many facets of tomorrow’s world. His keen interest in the advent of artificial intelligence enables him to cast a distinctive light on the challenges of this technological revolution.