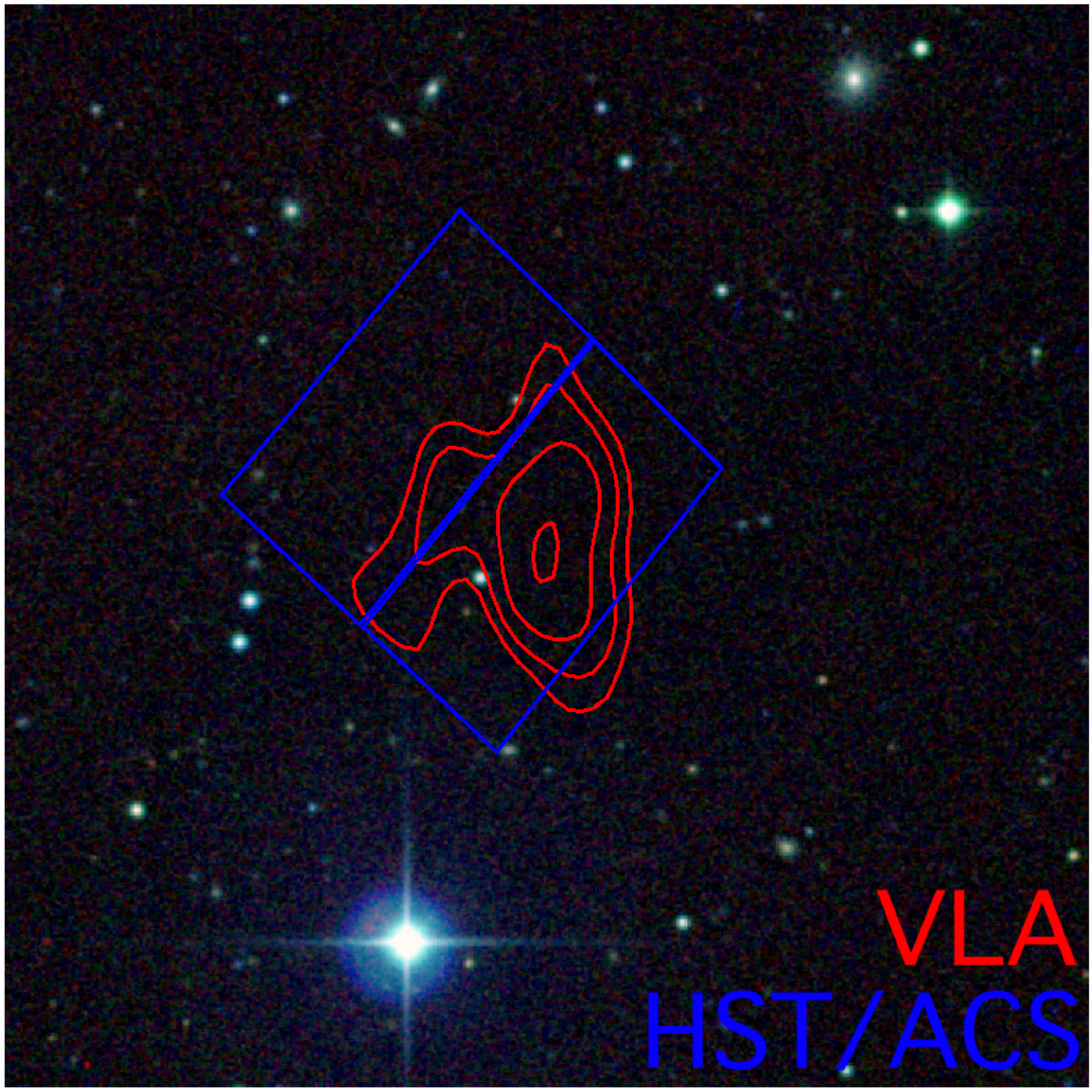

This Digitized Sky Survey image shows a patch of space roughly 14 million light-years away. The red lines mark the boundaries of a massive hydrogen gas cloud (Cloud-9) that cannot be seen with the naked eye. The blue square shows the region where astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm that no stars exist within the cloud. Credit: Gagandeep S. Anand et al 2025 ApJL 993 L55

A team led by Gagandeep Anand identified Cloud-9 as the first definitive example of a Reionization-Limited HI Cloud (RELHIC), a “failed galaxy” comprising a seemingly starless, compact cloud of hydrogen gas located near the spiral galaxy M94.

This discovery validates a fundamental prediction of the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (CDM) cosmological model: the existence of dark matter halos that capture gas but fail to form stars because the gas remains in thermal equilibrium and does not cool sufficiently for collapse.

Cloud-9’s estimated 100 million solar mass dark matter halo positions it at the critical mass threshold where galaxy formation becomes inefficient, demonstrating that not every dark matter halo will host a galaxy, as predicted by theory.

The identification involved a multi-telescope campaign utilizing FAST, the Green Bank Telescope, and the Very Large Array for gas characterization, with the Hubble Space Telescope conclusively confirming the absence of significant stellar populations, which would typically be present in a successful galaxy of comparable gas mass.

How do you find a galaxy that never formed? The standard cosmological model predicts the existence of “failed” galaxies — clumps of dark matter that captured gas but never birthed a star. Because they lack starlight, these theoretical clouds are nearly impossible to see, and until now, scientists had yet to identify a definitive example.

That changed when a team led by Gagandeep Anand, senior staff scientist of the Space Telescope Science Institute’s (STScI) Advanced Camera for Surveys group, discovered Cloud-9. The team’s findings were published on Nov. 10, 2025, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Rachael Beaton, astronomer at the STScI and study co-author, presented details of the discovery during a Jan. 5 press conference at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

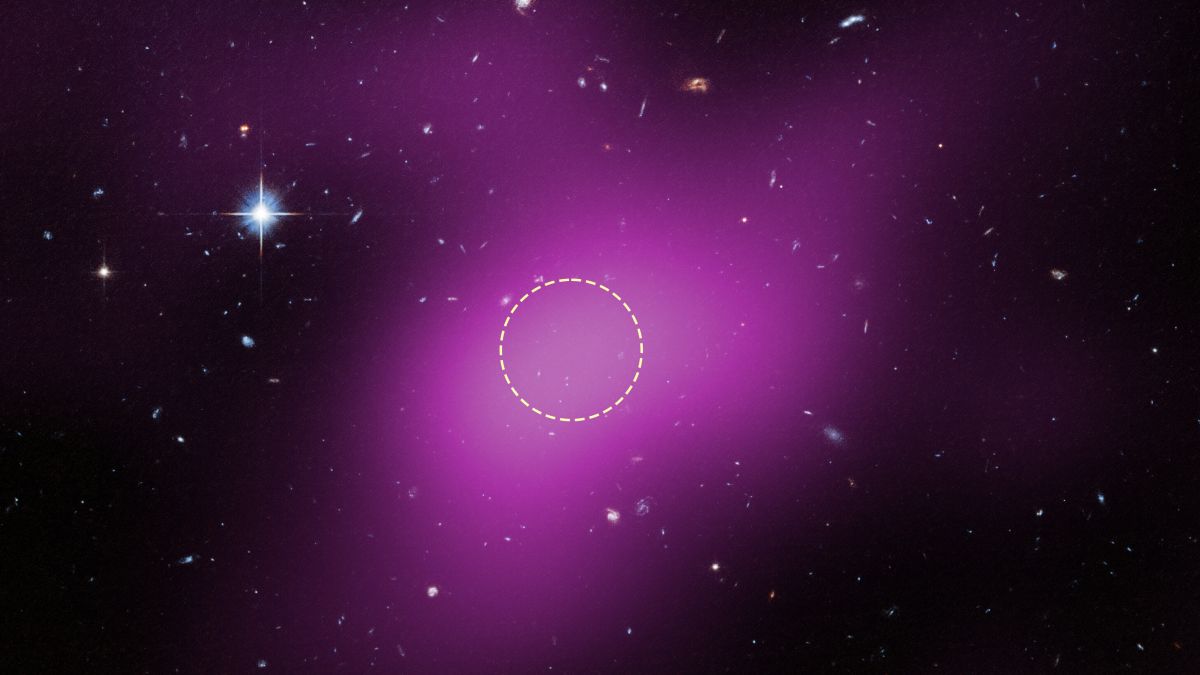

Cloud-9 is a seemingly starless, compact cloud of hydrogen gas near the spiral galaxy M94, roughly 14 million light-years away. According to the study, Cloud-9 appears to be a Reionization-Limited HI Cloud (RELHIC), the exact sort of failed galaxy predicted by the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (CDM) model of cosmology.

“This is the most convincing example of a ‘failed galaxy’ or a relic of the time that galaxies were forming,” Beaton said during the press conference. “This confirms a fundamental prediction of Lambda CDM, which is once you get below some mass scale, not every dark matter halo will have a galaxy in it.”

What is a RELHIC?

RELHICs are theoretical spherical clouds, the halos of structural dark matter that have successfully pulled in hydrogen gas (a crucial step in galaxy formation) but failed to form stars. The key difference between a normal galaxy and a RELHIC is how the gas behaves. In a typical galaxy, gas cools and collapses, reaching the high densities necessary to birth stars. In a RELHIC, however, the gas is in a state of thermal equilibrium with the rest of the universe. It never cools and therefore never collapses into stars. In the press conference, Beaton described the gas in Cloud-9 as being “as happy as it can be.”

Lambda CDM predicts a critical mass threshold at which galaxy formation becomes inefficient but not impossible. This threshold is where RELHICS thrive. Cloud-9 is estimated to reside within a dark matter halo of approximately 100 million solar masses — a weight that puts it right at the edge of this theoretical limit. The dark matter halo provides just enough gravitational pull to trap its 1 million solar masses of hydrogen gas and prevent it from drifting away, but it sits just below the mass required to overcome the gas’s internal temperature. Because the dark matter lacks the muscle to force this warm gas to collapse into a dense core, the result is a stalemate where the cloud is trapped by gravity but unable to ignite into stars.

According to simulations, RELHICs are, however, susceptible to a force known as ram pressure stripping. Essentially, hot, low-density gas floats among galaxy clusters and around large galaxies, acting as a sort of cosmic wind that strips gas away from smaller objects and morphs their shape. For galaxies that are already producing stars, this process can halt star formation. For RELHICs, it can stretch them into a less-than-perfect, oblong sphere.

While lying below the critical mass threshold set the stage for its failure, several other factors likely prevented Cloud-9 from ever collapsing into stars. As Beaton explained, “star formation needs something that causes that gas to collapse.” Cloud-9 never experienced that trigger. It is possible that Cloud-9 formed far away from other galaxies, isolated from the external triggers that can cause gas to lose heat, increase density, and collapse. It may also be a matter of timing. “It could be that the halo formed, and then it kind of got its gas too late for that trigger to happen,” Beaton said. “And then now, eventually 13, 14 billion years later, it’s finally entering the sort of gravitational sphere of influence of its parent galaxy, and now you’re seeing some of that ram pressure stripping and other things happening.” Regardless, Cloud-9 appears to remain starless.

How do you find one?

So if there are no stars for astronomers to spot, how do you find a RELHIC? The search involved a multi-telescope hunt. First, the team had to find a spherical cloud of hydrogen gas that resembled a galaxy.

Over the last few years, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in China has found several RELHIC candidates while surveying the night sky in neutral hydrogen, but Cloud-9 was distinct. Its properties more closely resembled what scientists expected from a RELHIC than any of the other candidate clouds did. It was a “perfect spherical cloud that looked like a dwarf galaxy,” Beaton explained. Yet, the gas in Cloud-9 didn’t appear to be rotating like typical galaxies, increasing the odds that it was starless. The FAST’s wide view couldn’t confirm, however, whether stars were hiding inside.

To verify the find, researchers turned to the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, which not only confirmed the cloud but found even more hydrogen than the original survey — roughly 1 million solar masses of gas.

The team then utilized the Very Large Array in New Mexico to create a high-resolution map of the gas. This showed that the cloud wasn’t perfectly spherical; it was slightly distorted. “But that kind of makes sense,” Beaton explained. Cloud-9 is “in the outer part of this galaxy where it’s experiencing ram pressure stripping … Whatever’s out there is kind of interacting with that gas, which is expected.” Essentially, the otherwise stable cloud is slowly being tugged on by the hot, low-density gas blowing through the outskirts of M94 — just as scientists predicted.

The final and most crucial step was proving that there were no stars in the cloud — that it wasn’t in fact a true galaxy. This search was conducted by the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble spent eight orbits staring at the exact coordinates of the gas cloud to see if any stars resided there. The composite image from Hubble’s observations revealed next to nothing – which is exactly what the team hoped to find.

According to simulations, a typical “successful” dwarf galaxy with this much gas would have a stellar mass of roughly 100,000 suns. That means, if Cloud-9 were a galaxy, Hubble should have easily resolved thousands of stars. It didn’t. Instead, Beaton joked, “We found one? Question mark?”

It’s difficult to prove what’s not there. To validate this null result, the team ran simulations to see what Cloud-9 would look like from Hubble’s perspective if it had formed stars. They modeled images of galaxies with different stellar masses and compared them to Hubble’s image. While a typical galaxy of this size would host about 100,000 suns’ worth of stars, the only simulation that looked anything like the Cloud-9 was of a simulated galaxy with 1,000 stellar mass. It’s highly unlikely that a galaxy with the mass of Cloud-9 would have such a low stellar mass. In fact, “there’s nothing like this that we found so far in the universe,” Beaton noted. While Cloud-9 may host an unprecedentedly faint dwarf galaxy, there is stronger evidence that Cloud-9 is a starless RELHIC.

Why does it matter?

Ultimately, Cloud-9 serves as a bridge between theory and observation, confirming that a dark matter halo mass threshold exists where galaxy formation becomes inefficient. At this threshold, outcomes “range from halos entirely devoid of stars to those able to form faint dwarfs,” the authors note in the paper.

Cloud-9 is “the first known system that clearly signals this predicted transition, likely placing it among the rare RELHICs that inhabit the boundary between failed and successful galaxy formation. Regardless of its ultimate nature, Cloud-9 is unlike any dark, gas-rich source detected to date,” the authors conclude.